AI in week 6

(Find the English version below/online!)

Ik stond deze week met fijne collega Izaak Dekker van HvA in Trouw met een stuk over het belang van frictie.

In een wereld waarin sociale media voortdurend op korte aandachtsspannes inspeelt is het lastig aandacht te leren opbrengen – terwijl dat de kern is van leren. Chatbots prioriteren echter gebruiksgemak en minimaliseren de noodzaak voor verdiepend werk, geduld en aandacht door ‘saaie’ taken te automatiseren en onmiddellijk klaar te staan met een antwoord.

Zoals Simone Weil zei: "the development of the faculty of attention forms the real object and almost the sole interest of studies." Ook werd ik geïnterviewd voor FD, en verscheen er een heel erg fijn verslag van een lezing van mij in het blad van de HvA.

En, ik schreef voor de zomer al over de absoluut geweldige show van Judy Lijdsman, en komende donderdag (12 feb) is de allerlaatste keer dat je 'm kan zien en nog wel op een toplocatie, in NEMO! (heb geen aandelen Judy verder, heb gewoon echt genoten van haar show!)

Kort over Moltbook

Nou de singularity is here hoor, in de vorm sociaal netwerk Moltbook!

Ik schreef er al even over op Mastodon, met een referentie naar de Heider-Simmel-illusie (en niet voor het eerst) Misschien ook nog wel interessant in dat kader is een stuk uit de Atlantic van vorige maand—ja dat tabje stond al lang open—dat goed laat zien hoeveel van de zogezegde intelligentie van generatieve leunt op simpelweg onthouden. Alhoewel tech bedrijven ontkennen dat de modellen hele stukken tekst opslaan, en zeggen dat de modellen er alleen van leren, zoals een mens dat zou doen, blijkt uit onderzoek van Standford en Yale dat dat niet waar is. Ook dat is een bevinding die weer twijfel aan "de AIs denken zoals mensen" onderbouwt.

Wil je er nu nog meer over lezen? Ik vond dit stuk in Wired geestig, vooral de take dat de coolste clubs altijd die zijn waar jij niet bij mag. Dus natuurlijk kan je het dan als mensen niet laten om je "greasy, carbon-based fingers in there" te krijgen om te gaan posten! Auteur Reece Rogers laat zien hoe makkelijk het is om als mens op Moltbook te komen wat meteen al vragen oproept over hoeveel van de content echt uit agents komt en niet uit mensen met happy prompt fingers. Rogers weet meteen al wat hij als eerste gaat posten... "Hello World" (Alhoewel een echte nerd natuurlijk "Hello, world" zou schrijven). Uiteindelijk komt hij natuurlijk tot een ontnuchterende conclusie:

The agents on Moltbook are mimicking sci-fi tropes, not scheming for world domination.

Wat ís prompt engineering?

Ow, wat een verdriet... Marcel Bucher, plantwetenschapper in Keulen is, door het aanzetten van een privacy feature, twee jaar aan chats met ChatGPT kwijt, en krijgt die niet meer terug. Ellende, die hij dus uitgebreid in Nature (!) mag beschrijven, net als mensen die een tijdje terug klaagden over "prompt stealing" en zelfs een tool maakten om te zorgen dat prompts niet gestolen konden worden uit AI gegenereerde plaatjs.

En aan de ene kant denk ik, ik heb nog ergens een minuscuul viooltje voor jou liggen, Marcel. Maar aan de andere kant, universiteiten pushen deze tools voortdurend, ik breng nog even mijn eigen werkgever in herinnering die opschrijft dat generatieve AI een krachtig hulpmiddel is voor elke docent. Doet deze man niet gewoon wat er van hem verwacht wordt, en ligt er dus niet ook (met de nadruk op ook) een verantwoordelijkheid bij wie dat propageert.

En misschien moeten we ook nadenken over wat de taak is die Bucher hier aan het uitvoeren was; het invoeren van zo goed mogelijke vragen in een chatprogramma, ook wel "prompt engineering" genoemd. Wat is dat?

Natuurlijk, er is een vaardigheid in het stellen van goede vragen, daar kan je beter in worden, maar dat hangt natuurlijk, net als zoveel andere vaardigheden totaal af van domeinkennis. Ik kan goede vragen stellen bij een stuk over over onderwijskunde, maar niet over de financiële situatie in Letland in de jaren '80. Prompt engineering is dus niet alleen het stellen van goede vragen zijn, fans ervan trekken een heel register open om de antwoorden beter te maken, "speel mijn meeste kritische tegenlezer", "vergeet niks", "doe alsof je een kritische journalist bent". Nu werken dat soort prompts helemaal niet, maar erger nog, ze geven de vragen een soort glans, alsof jij als enige weet hoe je die onvoorspelbare machine ertoe kan dwingen om zijn geheimen prijs te geven.

Terwijl het natuurlijk gewoon een statistisch model is, een slot machine met letters in plaats van vlammetjes! En die glans krijgt de vaardigheid natuurlijk ook door de term: prompt engineering.

Die term is enorm boeiend, en wie weet schrijf ik daar nog wel eens echt een lang stuk over, want wat is er nu eigenlijk engineering aan? Wat is engineering? Wikipedia to the rescue met deze mooie definitie uit 1947:

Het creatief toepassen van natuurwetten bij het ontwerpen en ontwikkelen van constructies, machines, apparatuur of productieprocessen, of werkzaamheden die hiervan gebruikmaken in meerdere of mindere mate; of een vergelijkbaar onderdeel te ontwerpen en daarbij bewust zijn van de gehanteerde uitgangspunten en normen. Of om hun gedrag bij specifieke (extreme) omstandigheden te voorspellen. Dit alles met als doel het veilig en economisch realiseren van de vooraf opgestelde functie en het minimaliseren van materiaalschade.

Engineering gaat dus over ontwerpen en ontwikkelen van iets op veilige en economische wijze, voldoend aan een vooraf opgestelde functie waarbij je rekening moet houden met natuurwetten.

Als je dat zo leest is het heel raar om deze term te gebruiken voor chatten met een chatbot, want voor het schrijven van het tekst zijn vaak geen strakke vooraf opgestelde functies, hooguit een woordenaantal, en de beste teksten, kunst en andere uitingsvormen spelen vaak met vorm, omdat je niet gebonden bent aan natuurwetten of het minimaliseren van schade. Je kan gewoon een liedje met grammaticaal totaal onjuiste zinnen maken en toch uitgeroepen worden tot het beste Nederlandse lied ooit.

Het is bijna beledigend dat prompt engineering, want engineering gaat over controleerbaar maken, over precies zijn, over de kans op fouten en materiaalschade meetbaar kleiner maken. Geen wonder natuurlijk dat deze term aanslaat, want het maakt iets dat onprecies is—een slot machine dus—tot een echte serieuze vaardigheid. Denken dat je echt iets kan, terwijl het in werkelijkheid een kansspel is, dat kennen we uit Flow van Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi! Flow kan goed zijn, als je echt lekker in een stuk tekst of code zit, maar kan je ook voor de gek houden:

Poker players are convinced it is their ability, and not chance, that makes them win. [...] In general, players of games of chance often believe that they have the gift of seeing into the future, at least within the restricted set of goals and rules that defines their game. And this most ancient feeling of control—whose precursors include the rituals of divination so prevalent in every culture—is one of the greatest attractions the experience of gambling offers.

Dus je kan je sowieso al afvragen of het een vaardigheid is. Maar waarom noemen ze het engineering? Het had ook prompt art, of prompt skills (al dat niet met een z) kunnen heten.

Maar wie in de informatica zit, herkent deze dynamiek natuurlijk meteen! Programmeren, een vaardigheid die ook aspecten heeft van de rommeligheid van taal, een proces waarin je door te programmeren soms tot nieuwe inzichten komt, werd ook 'veringenieurd' om zich de glans van wiskundige precisie en technisch vernuft toe te eigenen, werd in de jaren '60 "Software Engineering" (dat proces had trouwens ook tot gevolg dat vrouwen in de informatica verlieten).

En het stuk van programmeren dat zich bezig houdt met je verdiepen in de klant, weet je hoe ze dat noemen?! Empathie 1? Begrijpen en luisteren? Nee, hahahaha! Dat heet, I kid you not, "Requirements Engineering".

Dus vlieg op met die term prompt engineering. Het is geen engineering, het is lekker aanprutsen met een machientje, rommelen, klooien. Het is geen engineering, net zo goed als het is geen experimenteren is als je geen hypothese stelt en geen metingen doet, dan het is spelen. Professor Bucher found out the hard way, Professor De Sutter found out the hard way, en zo zullen er nog wel wat volgen.

AI in het onderwijs, vanuit welke bril?

Regelmatig verbaas ik me over de verscheidenheid aan meningen over AI. Hoe kan het nu toch dat er zó anders naar gekeken wordt? Deze fijne post van de altijd scherpe Ben Williamson schept orde in de chaos (hij kwam in week 50 vorig jaar ook langs). Williamson verwijst naar een eerder paper van Rebecca Eynon and Erin Young waarin zij drie verschillende soorten perspectieven op AI onderscheiden. Hij zegt over hun werk:

Academics interested in developing AI in education [...] frame AI as a methodology for advancing insights into processes and practices of learning and teaching.

Industry [...] frames AI as the basis for market expansion and profit. Finally, policymakers [...] tend to frame AI in terms of legitimizing reformatory aims, such as upskilling economically productive knowledge workers.

Williamson voegt nog een aantal categorieën toe (advocates, pragmatists en evangelizers), maar dat onderscheid vind ik niet zo heel betekenisvol. Maar het idee dat er een verschil is, wel! Ik maak de indeling niet op basis van identiteit, maar op basis van welke vraag er nu beantwoord wordt over AI in het onderwijs.

Sommige mensen, realiseerde ik me door het stuk van Williamson, beantwoorden de vraag "Kan AI, onder de beste omstandigheden, leren bevorderen?" Dat zagen we bijvoorbeeld in een stuk in de Volkskrant deze week over hoe AI helpt bij wiskunde. Negen examenleerlingen gaan met AI werken, onder leiding van een van zijn pensioen teruggekeerde docent en hun prestaties verbeteren! Er zijn methodologisch allerhande vragen te stellen bij zo'n studie: is dit niet gewoon "time on task"; ze hebben meer geoefend en doen het daarom beter? De gepensioneerde docent had misschien ook mooie werkvellen kunnen maken (met of zonder AI). Of is de nieuwigheid de aantrekkingskracht en gaat dat er na verloop van tijd weer af? Zoals onderzoeker Siri Beerends in het stuk opmerkt:

‘Het begint altijd met enthousiasme’, zegt ze. ‘Iedereen is verblind door optimistische vergezichten. Pas later blijkt het ingewikkelder.’

Maar kan AI helpen? Ik ben niet te flauw om toe te geven dat zelfs ik denk dat het antwoord daarop ja is. Ja het kan, net als er leerlingen zijn die een oefentoets echt eerst zelf maken en dan pas het antwoordenboekje erbij pakken, leerlingen die uit vrij wil Wikipedia lezen en editen, en leerlingen die extra oefenen met DuoLingo. Het kan. Maar is het eerlijk dat we dit van leerlingen verwachten als wij als volwassenen niet van de suikerpot af kunnen blijven? Dat lukt niet eens—echt mensen, De Speld had het niet beter kunnen bedenken—een wetenschapper die een boek schrijft getiteld Waarheid! Dezelfde man die dezelfde fout van rector De Sutter een "pijnlijk verhaal" en "gênant" noemde, en zei:

Er zit ook een beetje de trots in van universiteiten om heel erudiet over te komen, met heel veel citaten van allerlei beroemdheden uit het verleden. Terwijl vandaag de functie van een universiteit ook wel een praktische managementfunctie is en veel mensen minder erudiet zijn dan ze willen laten uitschijnen.

(Hij ontkent overigens dat zíjn fouten door AI komen).

De vraag of het kan is voor mij dus niet de relevantste vraag als de kans zo klein is dat het verantwoord gebruikt gaat worden. Ik beantwoord veel vaker de vraag "Is het waarschijnlijk dat AI leerlingen gaat helpen met leren?" Daarop is het antwoord denk ik nee. We zagen het aan de resultaten van het onderzoek van Khan Academy zelf vorige week. Het is niet waarschijnlijk, en wie zal er dan het meest van profiteren? Uit onderzoek onder volwassenen blijkt dat mensen "with stronger metacognition—the ability to plan, evaluate, monitor, and refine their thinking—are more likely to experience creative gains from using generative AI". Zo zal het ongetwijfeld voor leerlingen ook werken. Dat laat zich raden, leerlingen met veel voorkennis, sterke leesvaardigheid en vocabulaire, en die thuis vaak ook nog eens aangemoedigd en gefaciliteerd worden om slim met de AI te oefenen.

Of de vraag "Wegen de voordelen op tegen de nadelen?" Zelfs AI-fan Tom Naberink geeft toe in dat stuk in Volkskrant!

Hij waarschuwt voor wat hij ‘cognitieve luiheid’ noemt: leerlingen die AI gebruiken zonder goed na te denken over wat ze doen. Dat geldt volgens hem voor het merendeel: ‘Ze besteden hun denkwerk uit en controleren nauwelijks wat eruit komt. Dat vinden docenten zorgelijk, en terecht.’

Je zou bijna zeggen dat je met zulke vijanden geen vrienden meer nodig hebt!

En ja, voor die cognitieve luiheid komt nu ook wetenschappelijke onderbouwing. Een studie van de universiteit van Pennsylvania vergeleek traditionele websearch met zoeken met een LLM in twee experimenten met samen meer dan 14000 deelnemers, en wat bleek:

[...] those who learn from LLM syntheses (vs. traditional web links) feel less invested in forming their advice, and, more importantly, create advice that is sparser, less original, and ultimately less likely to be adopted by recipients. [Dit was de eerste studie met ca 1000 deelnemers]

Results from seven online and laboratory experiments (n = 10,462) lend support for these predictions, and confirm, for example, that participants reported developing shallower knowledge from LLM summaries even when the results were augmented by real-time web links.

Precies wat je zou verwachten, en precies wat Dekker en ik ook schrijven in dat stuk in Trouw dus. En dan heeft web search zelf ook al weer nadelen, en is dus maar een zwakke baseline, aldus The Knowledge Illusion [[1]] :

Two independent research groups have discovered that we have the same kind of “confusion at the frontier” when we search the Internet. Adrian Ward, a psychologist at the University of Texas, found that engaging in Internet searches increased people’s cognitive self-esteem, their sense of their own ability to remember and process information.

Maar als de meeste leerlingen iets niet goed gebruiken, waarom moeten we het dan toch proberen te integreren? Is het slim om leerlingen aan te moedigen om het te gebruiken, als het zo moeilijk is om het goed te gebruiken? En dan hebben we het alleen nog over cognitieve nadelen, en niet over andere nadelen buiten de klas zoals milieu-impact en meer macht voor techbros?

En er zijn nog zoveel andere vragen. De vraag "Is AI het beste dat we kunnen doen om het onderwijs beter te maken?" Nou hier twijfel ik niet aan het antwoord. Er is zoveel dat we kunnen doen, morgen, om onderwijs beter te maken. Minder focus op toetsen en cijfers (en daarmee dus ook minder nakijkdruk zonder dure AI), kleinere klassen, of een gratis schoolontbijt zodat kinderen niet hongerig in de klas zitten. Of, radicaal, I know, evidence based interventies zoals Erik Ex betoogde in Trouw. Het belangrijkste probleem met AI voor mij is dat het een red herring is, iets waar iedereen het over heeft, en waar onvermijdelijk bakken met geld heengaat, terwijl de kranten niet volstaan met opiniestukken over andere oplossingen. De opportunity costs zijn enorm.

Ik geef ook dit semester weer een vak op de VU genaamd "AI in het onderwijs" en de eerste opdracht die ik studenten heb gegeven is nadenken over hun visie van goed onderwijs en de doelen daarvan. Dat vinden ze soms raar, omdat het, denken ze, niet over AI gaat. Om ze in de denkmodus te krijgen zei ik: stel je voor dat al jouw leerlingen later op de Zuidas gaan werken, ben je dan blij omdat je sociale mobiliteit teweeg hebt gebracht, of droevig omdat ze niet de wereldburgers zijn geworden die je graag had gezien? Verschillende antwoorden op die vraag zijn waarschijnlijk ook verschillende antwoorden op de vraag hoe AI een plek moet krijgen in de klas.

Ik zou graag meer stukken willen lezen waarin mensen die voorstander zijn van AI gevraagd wordt op welke vraag ze nu eigenlijk het antwoord geven, vaak blijft dit onbenoemd.

[[1]]: Pagina 115. Had te veel leuke dingen te doen deze week, dus geen tijd meer om hier de originele bron te lezen, maar zij verwijzen naar deze twee papers. Het boek is uit 2017 dus dat zullen we maar vertrouwen.

En dan nog even dit!

- Soms is grappen maken het beste wat je kan doen in een droevige wereld, en deze fossil fuel themed meditatie-app is een heerlijk voorbeeld!

- Vorige week complimenteerde ik Khan Academy dus met hun onderzoek naar hun eigen tool, nu is er werk van Anthropic die het effect van hun eigen coding assistent Claude.ai bekeken hebben (Deze tip kreeg ik van lezer Iman en van vriend Leif!)

Ze vinden wat we eigenlijk al wisten, maar juist omdat van de makers zelf maakt het indruk. In een randomized control trial met 52 beginnende developers mocht de helft wel en de andere helft geen AI gebruiken, waarna de groepen allebei een toets kregen en een vragenlijst.

Hielp de AI? Ja, de test groep was 2 minuten sneller. Maar op de toets scoorde de AI groep 50%, maar de niet AI groep 67%. Vooral op de vragen over debugging was het verschil groot, "suggesting that the ability to understand when code is incorrect and why it fails may be a particular area of concern if AI impedes coding development".

Maar to be fair, er waren ook een paar usage patterns die het goed deden! Twee deelnemers volgden, wat de onderzoekers generation-then-comprehension noemden, eerst met AI code genereren en dan goed nadenken wat het doet. Die waren langzaam maar scoorden goed op de toets. En de groep van zeven die conceptual inquiry deden, en niet om code vroeg maar alleen vragen stelde deed het ook goed en was ook vrij vlot, paradoxaal genoeg dus want ze schreven de code niet met AI. - Is social media slecht voor tieners? Nee, er is geen smoking gun schrijft journalist Mathew Ingram. En dan denk je misschien, hela, las ik niet laatst dat Meta instagram in interne documenten zelf ene drug noemde? Jawel, dat las je wel en ik geloof ook dat dat waar is. Ik weet dat het bijna niet mogelijk is om die twee gedachten in je hoofd te houden, maar ik kan het prima verenigen. Ja, Silicon Valley programmeert hun socials om zo verslavend mogelijk te zijn, en sommige kinderen leiden daaronder, en ernstig ook. Maar het kan ook goed zijn, mooi, verbindend en soms de enige plek van veiligheid. Het heeft ook voordelen, en dus moeten we de algoritmes beter reguleren!

- Ook van Mathew Ingram (ik heb m ontdekt deze week en een paar stukk van m gelezen, allemaal goed!) social media wordt minder sociaal, al sinds 2014 (!!) zeggen mensen het ieder jaar minder te gebruiken om met vrienden of nieuwe mensen te kletsen, en meer om celebs te volgen en als tijdverdrijf.

- Een dataset van orgels in kerken werpt nieuw licht op klimaatverandering, omdat organisten hun orgels door temperatuursverschillen opnieuw moeten stemmen en ze daar in 18 verschillende kerken in de UK aantekeningen van hebben bijgehouden vanaf de jaren '60. Mooi voorbeeld van hoe data voor het ene doel voor iets totaal anders gebruikt kunnen worden (in dit geval voor iets goeds).

Goed nieuws

De Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens, die verantwoordelijk zijn voor het algoritmeregister kiest AI als een van de drie speerpunten, en wil, zo schrijft iBestuur "preventief kaders scheppen en risico’s in beeld brengen". Ik kan niet wachten!

iPhones en andere Apple apparaten hebben een Lockdown-modus die het zo goed als onmogelijk maakt om in te komen. Goed om te weten als je je zorgen maakt dat de overheid bij je data komt. Maf dat we in een wereld leven waarin ik niet als eerste denk aan het scenario waarin echte criminelen zich tegen de overheid kan beschermen...

Mooi stuk uit Nature van eind 2025 met 7x goed nieuws uit de wetenschap, waaronder vooruitgang in de strijd tegen van ebola, genetische modificatie en een afname van 43% mensen met pinda-allergie vergeleken met 2012, door kinderen er juist wel aan bloot te stellen, implementatie van een recent onderzoek.

Slecht nieuws

Honderden miljoenen berichten zijn gelekt uit de populaire app Chat & Ask AI, waaronder heftige berichten zoals vragen over self harm en het maken van drugs, rapporteert 404 media. Een security researcher kon door een verkeerde instelling van Google's database Firebase bij 300 miljioen berichten van meer dan 25 miljoen gebruikers, en rapporteerde het probleem, maar downloadde er ook 25 miljoen om te kijken wat er allemaal instond en dat was dus heel wat akeligs. En ook een "leuke" AI-knuffel voor kinderen bleek zo lek als een mandje, hackers hadden binnen een paar minuten 50.000 chatlogs in handen.

En weet je nog dat jailbreaken met SPoNGeFOnt?! Poëzie doet het ook. En OpenAI weet natuurlijk dondersgoed dat dit zo is, ze geven toe dat "prompt injections - text-based attacks on language models running in browsers - may never be completely eliminated." aldus een stuk in The Decoder.

Events, voor in de agenda!

Je kan me de komende tijd hier treffen:

- Zondag 15 februari in Amsterdam bij HUMA-CAFE in theater Perdu.

- Woensdag 4 maart bij de uitreiking van de AI Award. Ik vond het zelf ook een geestige verrassing maar ik ben een van de genomineerden!

- Donderdag 26 maart in Beeld & Geluid bij de lerarendag DG.

- Het duurt nog even, maar in juni geef ik in Antwerpen op DDD Europe een keynote getiteld "AI made me doubt everything about programming" waarin ik de geschiedenis van AI en programmeren induik en onderzoek hoe we naar ons vakgebied kijken voor en na AI.

Geniet van je boterham!

English

This week, wonderful colleague Izaak Dekker from HvA and I published an article in Trouw about the importance of friction (in Dutch, sadly).

In a world where social media constantly caters to short attention spans, it is difficult to learn to pay attention—even though that is the core of learning. However, chatbots prioritize ease of use and minimize the need for in-depth work, patience, and attention by automating “boring” tasks and providing immediate answers. [translated]

As Simone Weil said: "the development of the faculty of attention forms the real object and almost the sole interest of studies."

Briefly about Moltbook

Well, the singularity is here, in the form of the social network Moltbook...

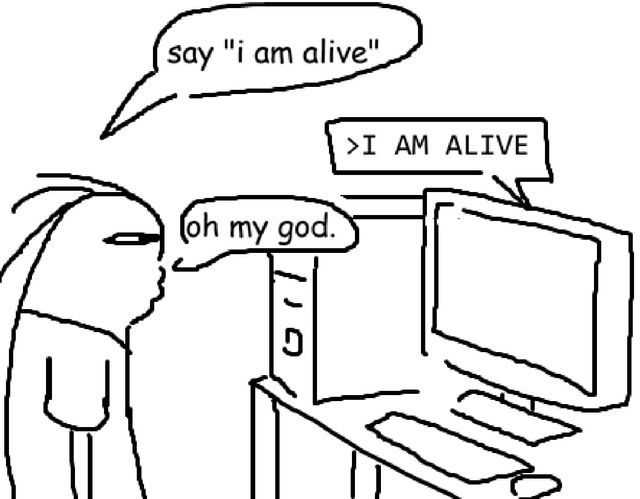

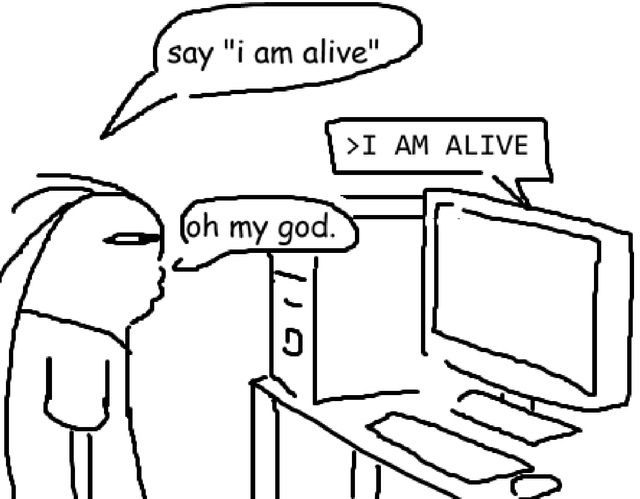

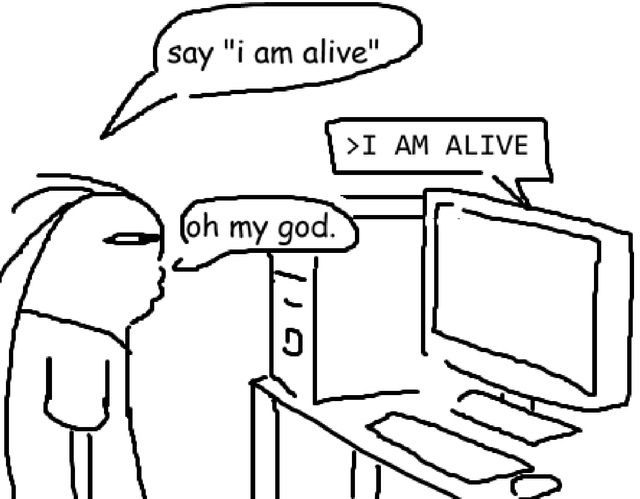

I already wrote about it briefly on Mastodon, with a reference to the Heider-Simmel illusion (and not for the first time). Perhaps also interesting in that context is an article from last month's Atlantic—yes, that tab has been open for a long time—which clearly shows how much of the so-called intelligence of generative AI relies on simple memorization. Although tech companies deny that the models store entire pieces of text, saying that the models only learn from them, as a human would, research by Stanford and Yale shows that this is not true. This is another finding that casts doubt on the idea that "AIs think like humans".

Want to read more about it? I found this piece in Wired amusing, especially the take that the coolest clubs are always the ones you can't get into. So of course, people can't resist getting their "greasy, carbon-based fingers in there" to start posting! Author Reece Rogers shows how easy it is for humans to get on Moltbook, which immediately raises questions about how much of the content really comes from agents and not from people with happy prompt fingers. Rogers knows right away what he's going to post first... "Hello World" (Although a real nerd would of course write "Hello, world"). Ultimately, of course, he comes to a sobering conclusion:

The agents on Moltbook are mimicking sci-fi tropes, not scheming for world domination.

What is prompt engineering?

Oh, such a tragedy... Marcel Bucher, a plant scientist in Cologne, lost two years of chats with ChatGPT by enabling a privacy feature, and he can't get them back. Misery, which he is allowed to describe in detail in Nature (!), just like people who complained a while back about "prompt stealing" and even created a tool to ensure that prompts couldn't be stolen from AI-generated images.

On the one hand, I'm like, I still have the tiniest violin for you somewhere, Marcel. But on the other hand, universities are constantly pushing these tools. I would like to remind you that my own employer writes that generative AI is a powerful tool for every teacher. Isn't this man just doing what is expected of him, and isn't there also (with the emphasis on also) a responsibility on the part of those who promote it?

And perhaps we should also think about the task Bucher was performing here: entering the best possible questions into a chat program, also known as "prompt engineering". What is that?

Of course, there is a skill in asking good questions, and you can get better at it, but that, like so many other skills, depends entirely on domain knowledge. I can ask good questions about a piece on educational science, but not about the financial situation in Latvia in the 1980s. Prompt engineering is therefore not just about asking good questions; fans of it pull out all the stops to improve the answers: "play my most critical proofreader", "don't forget anything", "pretend you're a critical journalist".

Now, those kinds of prompts don't work at all, but worse still, they give the questions a kind of glamour, as if you are the only one who knows how to force that unpredictable machine to reveal its secrets.

When of course it's just a statistical model, a slot machine with letters instead of flames! And that glamour is also given to the skill by the term: prompt engineering.

That term is extremely fascinating, and who knows, I might write a long piece about it someday, because what exactly is engineering about it? What is engineering? Wikipedia to the rescue with this beautiful definition from 1947:

The creative application of natural laws in the design and development of structures, machines, equipment, or production processes, or activities that use these to a greater or lesser extent; or to design a comparable component while being aware of the principles and standards used. Or to predict their behavior in specific (extreme) circumstances. All this with the aim of safely and economically realizing the predefined function and minimizing material damage.

Engineering is therefore about designing and developing something in a safe and economical way, fulfilling a predefined function while taking into account the laws of nature.

When you read it like that, it seems very strange to use this term for chatting with a chatbot, because writing text often does not involve strict predefined functions, at most a word count, and the best texts, art, and other forms of expression often play with form, because you are not bound by the laws of nature or the minimization of damage. You can simply write a song full of grammatically incorrect sentences and still be proclaimed the best Dutch song ever (couldn't come up with a good Dutch example)

It is almost insulting to call it prompt engineering, because engineering is about making things controllable, about being precise, about measurably reducing the chance of errors and material damage. No wonder, of course, that this term has caught on, because it turns something that is imprecise—a slot machine, in other words—into a real serious skill. Thinking you can really do something, when in reality it is a game of chance, is something we know from Flow by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi! Flow can be good, when you are really into a piece of text or code, but it can also fool you:

Poker players are convinced it is their ability, and not chance, that makes them win. [...] In general, players of games of chance often believe that they have the gift of seeing into the future, at least within the restricted set of goals and rules that defines their game. And this most ancient feeling of control—whose precursors include the rituals of divination so prevalent in every culture—is one of the greatest attractions the experience of gambling offers.

So you can already wonder whether it is a skill. But why do they call it engineering? It could just as well have been called prompt art, or prompt skills/z.

But anyone in computer science immediately recognizes this dynamic! Programming, a skill that also has aspects of the messiness of language, a process in which you sometimes gain new insights through programming, was also “engineered” to appropriate the glamour of mathematical precision and technical ingenuity, becoming “Software Engineering” in the 1960s (that process also resulted in women leaving computer science).

And the part of programming that involves getting to know the customer, do you know what they call that?! Empathy 1? Understanding and listening? No, hahahaha! It's called, I kid you not, requirements Engineering"

So please fork off with your "prompt engineering". It's not engineering, it's just messing around with a machine, fiddling, tinkering. It's not engineering, just as it's not experimentation if you don't formulate a hypothesis and take measurements; it's just playing. Professor Bucher found out the hard way, Professor De Sutter found out the hard way, and there will be plenty more.

AI in education, from what perspective?

I am regularly amazed by the diversity of opinions on AI. How is it possible that people view it so differently? This excellent post by the always sharp Ben Williamson brings order to the chaos (he also visited us in week 50 last year). Williamson refers to an earlier paper by Rebecca Eynon and Erin Young in which they distinguish three different perspectives on AI. He says about their work:

Academics interested in developing AI in education [...] frame AI as a methodology for advancing insights into processes and practices of learning and teaching.

Industry [...] frames AI as the basis for market expansion and profit. Finally, policymakers [...] tend to frame AI in terms of legitimizing reformatory aims, such as upskilling economically productive knowledge workers.

Williamson adds a number of categories (advocates, pragmatists, and evangelizers), but I don't find that distinction particularly meaningful. However, I do find the idea that there is a difference meaningful! I don't base the classification on identity, but on which question is being answered about AI in education.

Some people, I realized from Williamson's article, answer the question "Can AI, under the best circumstances, promote learning?" We saw this, for example, in an article in the Volkskrant this week about how AI helps with mathematics (Dutch) Nine final year students worked work with AI, under the guidance of one of their teachers who has returned from retirement and they improved a lot. There are all kinds of methodological questions to be asked about such a study: isn't this just “time on task”; they have practiced more and are therefore doing better? The retired teacher could also have created attractive worksheets (with or without AI). Or is it the novelty that attracts them, and will that wear off over time? As researcher Siri Beerends notes in the article:

“It always starts with enthusiasm,” she says. “Everyone is blinded by optimistic prospects. Only later does it turn out to be more complicated.”

And I'm not too shy to admit that even I think the answer to that is yes. Yes, it's possible, just as there are students who really do the practice test themselves first and only then pick up the answer book, students who read and edit Wikipedia because they want to, and students who practice with DuoLingo. It is possible. But is it fair that we expect this of students when we as adults can't stay away from the sugar bowl? Not even, really, folks, De Speld couldn't have come up with anything better: a scientist who writes a book titled Truth! The same guy who called Rector De Sutter's mistake a "painful story" and "embarrassing", and said:

There is also a bit of pride in universities to come across as very erudite, with lots of quotes from all kinds of famous people from the past. Whereas today, the function of a university is also a practical management function, and many people are less erudite than they would like to appear.

(He denies that his mistakes are caused by AI).

So for me, the question of whether it is possible is not the most relevant question if the chance of it being used responsibly is so small. I much more often answer the question "Is it likely that AI will help students learn?" To that, I think the answer is no.

We saw this in the results of Khan Academy's own research last week. It is not likely, and who will benefit most from it? Research among adults shows that people “with stronger metacognition—the ability to plan, evaluate, monitor, and refine their thinking—are more likely to experience creative gains from using generative AI.” This will undoubtedly work for students as well. It's easy to guess that students with a lot of prior knowledge, strong reading skills, and vocabulary, who are often encouraged and facilitated at home to practice using AI wisely, will benefit the most.

Or the question "Do the advantages outweigh the disadvantages?" Even AI -fan Tom Naberink admits this in his article in Volkskrant!

He warns against what he calls “cognitive laziness”: students who use AI without thinking carefully about what they are doing. According to him, this applies to the majority: “They outsource their thinking and hardly check what comes out. Teachers find this worrying, and rightly so.” [translated from Dutch]

You could almost say that with enemies like that, who needs friends?

And yes, there is now scientific evidence for this cognitive laziness. A study by the University of Pennsylvania compared traditional web searches with searches using an LLM in two experiments with a total of more than 14,000 participants, and the results showed that

[...] those who learn from LLM syntheses (vs. traditional web links) feel less invested in forming their advice, and, more importantly, create advice that is sparser, less original, and ultimately less likely to be adopted by recipients. [This was the first study with approximately 1,000 participants]

Results from seven online and laboratory experiments (n = 10,462) lend support for these predictions, and confirm, for example, that participants reported developing shallower knowledge from LLM summaries even when the results were augmented by real-time web links.

Exactly what you would expect, and exactly what Dekker and I also write in that article in Trouw. And then web search itself also has disadvantages, and is therefore only a weak baseline, according to The Knowledge Illusion [[11]] :

Two independent research groups have discovered that we have the same kind of “confusion at the frontier” when we search the Internet. Adrian Ward, a psychologist at the University of Texas, found that engaging in Internet searches increased people’s cognitive self-esteem, their sense of their own ability to remember and process information.

But if most students don't use it properly, why should we try to integrate it? Is it wise to encourage students to use it if it is so difficult to use it properly? And then we are only talking about cognitive disadvantages, not other disadvantages outside the classroom such as environmental impact and more power for techbros?

And there are so many other questions. The question "Is AI the best we can do to improve education?" Well, I have no doubt about the answer. There is so much we can do, tomorrow, to improve education. Less focus on tests and grades (and therefore less pressure to mark without expensive AI), smaller classes, or free school breakfasts so that children are not hungry in class. Or, radically, I know, evidence-based interventions, as Erik Ex argued in Trouw. The main problem with AI for me is that it's a red herring, something everyone is talking about, and where inevitably tons of money is being spent, while the newspapers are not full of opinion pieces about other solutions. The opportunity costs are enormous.

This semester, I am again teaching a course at VU called "AI in Education", and the first assignment I gave my students was to think about their vision of good education and its goals. They sometimes find this strange because, they think, it is not about AI.

To get them into thinking mode, I said: imagine that all your students will later work in the Zuidas business district. Would you be happy because you have brought about social mobility, or sad because they have not become the global citizens you would have liked to see? Different answers to that question are likely to be different answers to the question of how AI should be incorporated into the classroom.

I would like to read more articles in which people who are in favor of AI are asked which question they are actually answering, as this often remains unmentioned.

[[11]]: Page 115. I had too many fun things to do this week, so I didn't have time to read the original source, but they refer to these two papers. The book is from 2017, so we'll just have to trust that.

And then there's this!

- Sometimes making jokes is the best thing to do in a sad world, and this fossil fuel themed meditation app is a wonderful example!

- Last week, I complimented Khan Academy on their research into their own tool, and now there is work by Anthropic that has examined the effect of their own coding assistant Claude.ai. (I got this tip from reader Iman and friend Leif!)

They found what we already knew, but because it came from the creators themselves, I read it differently. In a randomized control trial with 52 novice developers, half were allowed to use AI and half were not. Afterward, both groups were given a test and a questionnaire.

Did AI help? Yes, the test group was 2 minutes faster. But on the test, the AI group scored 50%, while the non-AI group scored 67%. The difference was particularly large on the questions about debugging, "suggesting that the ability to understand when code is incorrect and why it fails may be a particular area of concern if AI impedes coding development".

But to be fair, there were also a few usage patterns that performed well! Two participants followed what the researchers called generation-then-comprehension, first generating code with AI and then thinking carefully about what it does. They were slow but scored well on the test. And the group of seven who did conceptual inquiry, and didn't ask for code but only asked questions, also did well and were quite fast, which is paradoxical because they didn't write the code with AI. - Is social media bad for teenagers? No, there is no smoking gun, writes journalist Mathew Ingram. And then you might think, hey, didn't I read recently that Meta itself called Instagram a drug in internal documents? Yes, you did read that, and I also believe it to be true. I know it's almost impossible to hold those two thoughts in your head, but they can be reconciled. Yes, Silicon Valley makes their social media as addictive as possible, and some children suffer from this, badly. But it can also be good, beautiful, connecting, and sometimes the only place of safety. It also has advantages, so we need to regulate the algorithms better!

- Also from Mathew Ingram (I discovered him this week and read a few of his pieces, all good!) social media has been becoming less social since 2014 (!!) people say they use it less every year to chat with friends or new people, and more to follow celebrities and as a pastime.

- A dataset of organs in churches sheds new light on climate change, because organists have to retune their organs due to temperature differences and have kept records of this in 18 different churches in the UK since the 1960s. A great example of how data collected for one purpose can be used for something completely different (in this case, for a good cause).

Good news

iPhones and other Apple devices have a Lockdown mode that makes it virtually impossible to access. Good to know if you're concerned about the government accessing your data. It's crazy that we live in a world where my first thought isn't about actual criminals protecting themselves from the government...

Nice article from Nature from late 2025 with 7 times good news from science, including progress in the fight against Ebola, genetic modification, and a 43% decrease in people with peanut allergies compared to 2012, by exposing children to them, implementation of a recent study.

Bad news

Hundreds of millions of messages have been leaked from the popular app Chat & Ask AI, including disturbing messages such as questions about self-harm and drug use, reports 404 media. A security researcher was able to access 300 million messages from more than 25 million users due to a misconfiguration of Google's Firebase database and reported the problem, but also downloaded 25 million messages to see what was in them, which turned out to be a lot of nasty stuff. And even a “cute” AI cuddly toy for children turned out to be as leaky as a sieve, with hackers getting their hands on 50,000 chat logs within a few minutes.

And remember jailbreaking with SPoNGeFOnt?! Poetry works too. And OpenAI knows very well that this is the case, admitting that "prompt injections - text-based attacks on language models running in browsers - may never be completely eliminated" according to an article in The Decoder.

Events, for your calendar!

You can find me here in the coming times:

- Sunday, February 15, in Amsterdam at HUMA-CAFE in the Perdu theater.

- Wednesday, March 4, at the AI Award ceremony. I thought it was a funny surprise, but I am one of the nominees!

- It's still a while away, but in June, I will be giving a keynote speech in Antwerp at DDD Europe entitled "AI made me doubt everything about programming", in which I will delve into the history of AI and programming and examine how we view our field before and after AI.

Enjoy your sandwich!

Member discussion