AI in week 5

Op veler verzoek... Een kortere nieuwsbrief! (Click here for English!)

Ik ga echt proberen me vanaf te beperken tot twee onderwerpen, zo hou ik hopelijk tijd over voor mijn boek. En ik stond deze week natuurlijk ook al weer in de Volkskrant met mijn vaste column, deze keer over emancipatie en student-evaluaties, dus als je Felienne te kort komt, kan je die nog even meepikken.

EdTech, nee, gewoon nee!

Het werkt gewoon... niet!

Geen verrassing voor wie deze nieuwsbrief leest, uiteraard, vorige week haalde ik Thomas Edison nog aan–voor de liefhebber trouwens hier een diep dive in de originele bronnen van die quote—en van de zomer had ik het nog uitgebreid over de mislukkingen van het One Laptop Per Child project en het daarbij behorende gedachtengoed van de informatici. Daaraan ga ik in mijn boek een heel hoofdstuk wijden; hoe mensen die zelf gek zijn op technologie (ik was er zelf vroeger ook eentje, trouwens) denken dat alle kinderen ook zo zullen zijn als ze eenmaal een laptop in handen hebben.

En hoewel ik weet dat het toch nooit echt echt tot mainstreamgedachtengoed door zal dringen—we zullen altijd Maurice de Honds blijven houden die niets van onderwijs weten en tóch beginnen over innoveren in scholen want ze zijn zo conservatief, al 100 jaar hetzelfde!—lijkt het erop dat meer mensen scepsis hierover beginnen te begrijpen. Zo verscheen er afgelopen week een stuk in The Economist—niet bepaald een blaadje voor linkse leraartjes—dat verhaalt over McPherson Middle School in Kansas waar ze in 2022 een laptopprogramma invoerden:

“We thought it was going to be really magical,” says Inge Esping, the principal.

It wasn’t. It “didn’t really move the needle”, Ms Esping says. Students found the programme repetitive, rigid and boring—and distraction proved irresistible once they were on their school-issued laptops.

Die afleiding doet het 'm iedere keer weer! Het is ook mijn ervaring, zoals ik eerder schreef, zodra je een laptop in de klas of collegezaal toelaat, verander je in een agent die de hele tijd "nee niet op YouTube" moet roepen en dat doet wat met je en met de klassevibe. En dit is dus geen anekdote, ze citeren een meta-analyse van Stanford (een paper over andere papers) dat 119 onderzoeken bekeek en wat bleek?:

found the studies described programmes that delivered at best only marginal gains on standardised tests. The majority had little effect, no effect or harmful ones.

Every single time. Soms vraag ik me af waarom we het blijven proberen, waarom is die mythe toch zo hardnekkig? Kudos wel voor de mensen van Khan Academy, die hun het gebruik van 200.000 gebruikers hebben geanalyseerd, en het ook niet echt is om over naar huis te schrijven. Ja, als je het gebruikt, gaat je cijfer wel omhoog. Maar... dat doen leerlingen/studenten niet:

24% of students have zero platform usage, 65% spend under 10 min per week (6 h per year), and only 10% meet KA’s recommendations of 18 h a year (approximately 30 min per week).

Die top 10% verbetert dan 0.085 tot 0.146 standaarddeviatie, wat best wat is, maar dat is dus echt een kleine groep van waarschijnlijk leerlingen die het al leuk vinden om te oefenen of daar thuis toe aangemoedigd worden. Het gemiddelde effect is maar 0.031 standaarddeviatie!

En wie moet er dan voor zorgen dat het meer gebruikt wordt? Ja, wij leraren:

Teachers might reduce achievement gaps and boost overall gains by encouraging more productive use of the platform (focused on skill mastery)—especially among struggling students.

Ook Jared Horvath schrijver van het boek "The Digital Delusion" komt aan het woord in het stuk van the Economist: "In nearly every context, ed tech doesn’t come close to the minimum threshold for meaningful learning impact." Sterker nog, kinderen op scholen met minder technologie doen het vaak beter, alhoewel daar uiteraard wel de vraag is of dat een causaal verband is, het kan ook goed zijn dan scholen waar het al niet best loopt, technologie zien als een oplossing. In any case, zelfs als het geen negatief resultaat heeft maar simpelweg geen is vrij bizar, voor iets dat scholen alleen al in Amerika $30 miljard kost (wereldwijd $165 miljard). Dat had ook naar scholen kunnen gaan, sluit het stuk droogjes af:

Back in 2013, Bill Gates remarked that it would take a decade to know whether education technology really worked. More than ten years and hundreds of billions of dollars later, the answer is increasingly clear. Notes Emily Cherkin, an advocate and fed-up parent: “Imagine if all that money had gone into teachers instead.”

Het is bijna alsof beter leren niet echt het doel is van techbedrijven..., maar, zoals NBC deze week schreef over Google, kinderen jong op hun platformen krijgen zodat ze levenslang klant blijven:

One internal November 2020 presentation slide said acclimating children to Google’s ecosystem in school would hopefully lead them to use its products as adults: “You get that loyalty early, and potentially for life.” Another undated slide deck suggested imagining a world where “Parents ask their children ‘Why aren’t you watching more YouTube?’” and “School Administrators shift budgets from Textbooks to YouTube subscriptions.”

En, zoals het artikel in het Economist dus ook benadrukte, het resultaat is vaak niet niks, maar slechter dan niks! Het kost geld dat we ook anders hadden kunnen besteden, het creëert de zoveelste publieke golf van kritiek op leraren, maar vooral, leerlingen zijn de dupe van niet-werkende technologie. Een heel uitgebreid rapport van onderzoeksinstituut Brookings komt tot de conclusie dat "de risico's van AI op dit moment de voordelen niet waard zijn". Het hele rapport staat bol van bevindingen zoals het stuk van de Economist, dus bookmarken maar om door te sturen naar de positivo's in je omgeving, maar deze zin brak mijn hart:

AI is doing things for students that they used to enjoy.

Studenten, zo schrijft AI-onderzoeker Siri Beerends, verdienen beter, die verdienen dat wij de rem zetten op hun deskilling, maar op de meeste plekken gebeurt het tegenovergestelde, AI wordt omarmd.

Geen wonder misschien dat studenten wegblijven uit het onderwijs, op de HvA is de aanwezigheid inmiddels nog maar 30%. Het is, volgens Izaak Dekker, een drietrapsraket:

Studenten zijn veel minder dan vroeger aanwezig bij colleges. Ze lezen zich minder goed in. En ze maken volop gebruik van kunstmatige intelligentie.

Dat is misschien wel makkelijker, maar het is niet leuker! Dat geldt natuurlijk niet alleen voor studenten, voor iedereen. Ja, een toets maken, een stuk schrijven, powerpoints voorbereiden, het is allemaal veel werk, maar het was toch ook lekker als het je gewoon gelukt was om iets goeds in elkaar te zetten, of zelfs maar iets "okees" als je niet al te veel tijd had. Al die kleine stukjes "yes, dat is me toch maar weer mooi gelukt" vallen weg als iedereen alles met AI gemaakt wordt. Genânt dus dat ook de VU, zoals nu.nl rapporteerde en daarbij ook mij bevroeg, met het zoveelste experiment doet met een AI avatar voor studenten om mee te chatten.

Zelfs saai werk heeft toch nog wel wat moois, zo kan je lezen in dit schitterende paper van onderzoekers van Frans onderzoeksinstituut Sciences Po, die zeven maanden onderzoek deden onder 32 participanten, de helft studenten die stage liepen en de andere helft professionals, die heel uitgebreid bestudeerd werden ("30 hours of group meetings, 8 hours of individual interviews, 400 pages of participants' written notes, and 600 LLM conversations"); een zeer goed voorbeeld van kwalitatief onderzoek, dat probeert te begrijpen en niet te meten.

En wat zegt daarin een van de deelnemers over het automatiseren van saaie klusjes:

Before [using the LLM], I used to do those tasks already, I didn’t have more or less work. It just wasn’t boring. I mean, I didn’t think of it as something super interesting, but it wasn’t boring either. And with the use of the LLM, it started to feel more and more boring. [...] It’s not just that it revealed something [about my work], but somehow, the way we use it creates the boredom.

Waarom blijven we dan toch die halleluja-verhalen maar horen? Misschien gaat dit ook wel over het verschil tussen de echte werkvloer en mensen die besluiten nemen. De Maurice de Honds van de wereld praten met schooldirecteuren, of in de meeste gevallen besturen van schoolstichtingen waar meestal tientallen scholen bij aangesloten zijn. Dat is ook zoiets dat je alleen weet als je zelf op een school werkt, en je vanuit de buitenwereld, zelfs vanuit een lerarenopleiding, niet goed ziet: in hoeverre de besluiten die op scholen genomen worden liggen bij mensen die zelf een afstand tot de scholen hebben, soms zelfs mensen die zelf nooit in het vo hebben lesgegeven.

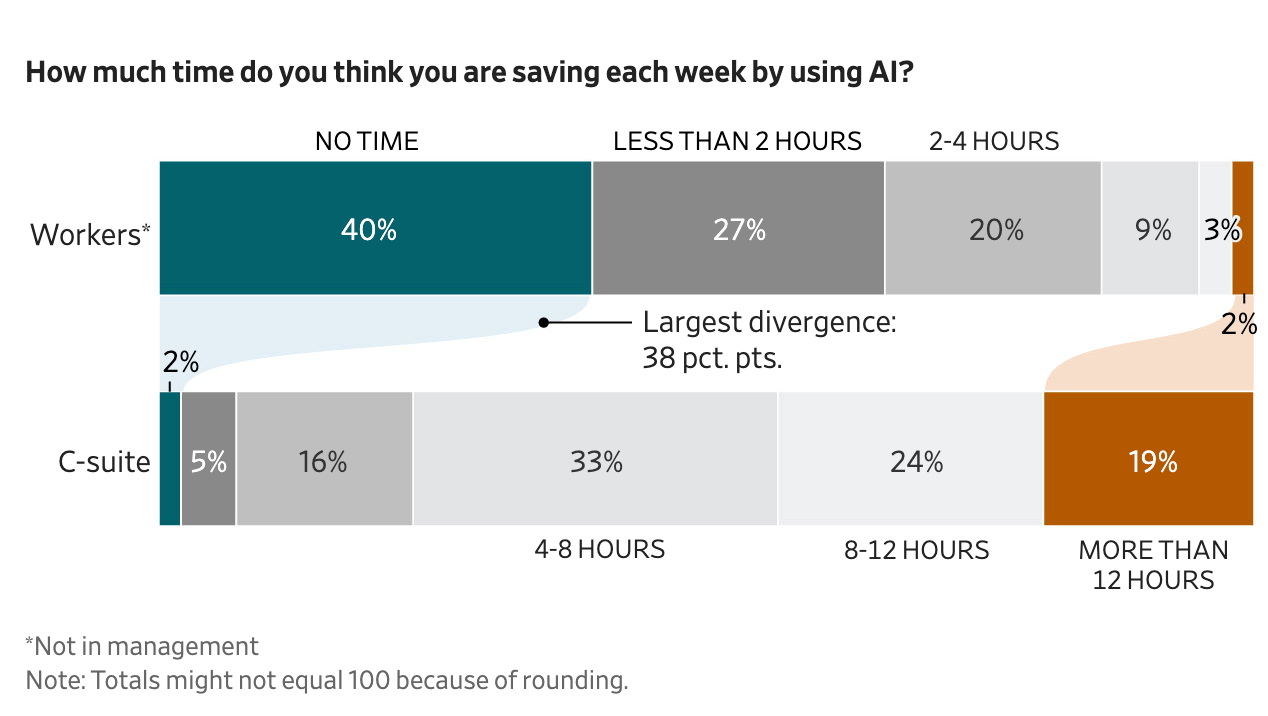

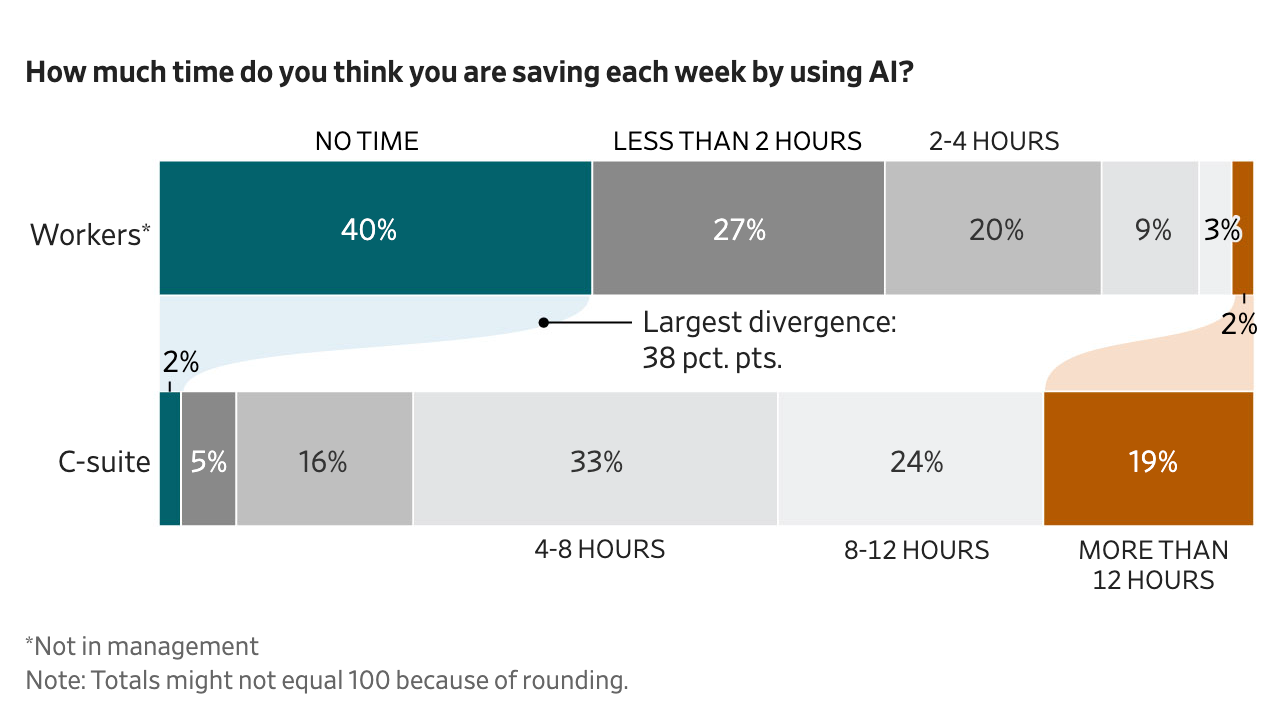

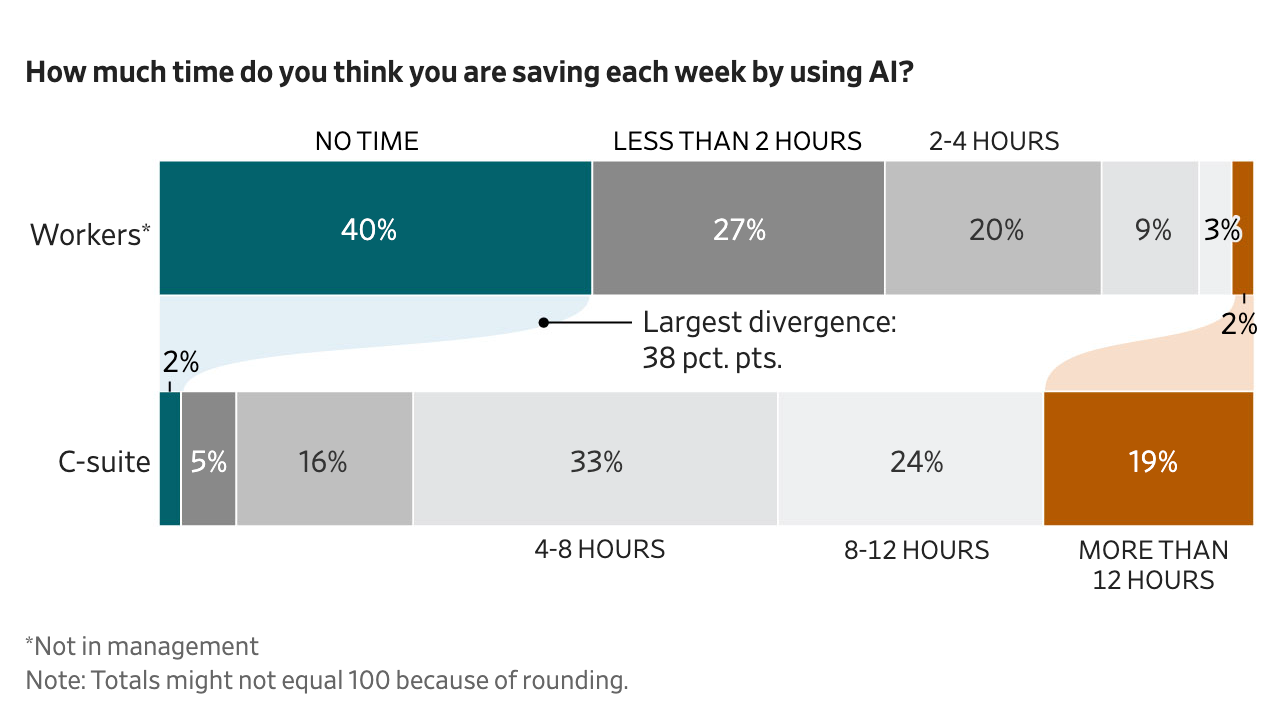

En díe maken de keuzes over technologie, met weinig overleg met leraren over wat zij willen, en natuurlijk kijken die heel anders naar de balans tussen kansen en risico's. In dit onderzoek onder 5000 Amerikaanse werknemers waarover Wallstreet Journal rapporteerde, zie je een enorm verschil tussen wat C-level denkt versus "gewone mensen":

Better is worse!

Vibe coden, werkt het en zo ja voor wie? Een paper in Science onderzocht 30 millioen GitHub commits (ingestuurde stukjes code) van meer dan 150.000 programmeurs, om te kijken hoeveel ervan door AI geschreven zijn. Dat deden ze ook weer met AI dus we moeten het resultaat misschien met een korreltje zout nemen hoor. Zij komen tot de conclusie dat zo'n 30% van alle Python code in de VS nu met AI geschreven is. En ze hebben ook gekeken naar welke programmeurs AI gebruiken, en vinden dat vooral ervaren programmeurs meer code zijn gaan schrijven (de auteurs noemen dat een "productivity gain", maar daar wil ik niet aan, meer code is niet perse beter, namelijk, dat weet echt iedere programmeur). Ook vinden ze, dat vind ik wel boeiend, dat ervaren programmeurs meer nieuwe soorten code gaan schrijven, libraries die ze nog niet kenden ("exploration gains", a la, daar kan ik mee leven). Maar schrijven ze ook:

For less experienced programmers, we observe no meaningful increases in productivity or exploration.

Nogmaals, omdat ze deze data niet met een vragenlijst of een plugin hebben verzameld, korrels zout zijn op de plaats. Het zou ook best kunnen dat beginnende programmeurs de afgelopen jaren hebben leren programmeren op basis van veel AI code, dus dat ze ook handmatig die stijl gebruiken. Lastig te zeggen, maar het verschil tussen beginners en ervaren programmeurs dat geloof ik wel en dat is interessant. Want hoe doen die beginners nog de ervaring op die ertoe leidt dat je dus verder in je carrière goed van die tools gebruik kan maken? Hoe leer je dan meer te doen dan de output een beetje scannen en gewoon maar 'inchecken' zoals dat heet? Die zorg heb ik niet alleen, ook de baas van een van de meest gebruikte vibe coding tool Cursor zegt dat:

“If you close your eyes and you don’t look at the code and you have AIs build things with shaky foundations as you add another floor, and another floor, and another floor, and another floor, things start to kind of crumble,” he said.

En als deze zorg niet al terecht was, dan wordt die dat wel, zo schrijft Jamie Triss in IEEE Spectrum, want de modellen worden slechter is zijn ervaring. En dat zit m in subtiele verschillen.

Wij software developers zeggen weleens gekscherend "worse is better" waarmee bedoeld wordt dat software soms beter wordt (beter) als die minder features heeft (worse). Ik herken dat heel erg, toen ik net aan Hedy werkte, stopte we het vol met coole features en opties, en na een tijdje hebben we veel daarvan weer weggehaald, omdat het log werd, en onoverzichtelijk.

Hier lijkt het tegenovergestelde aan de hand, namelijk "better is worse". Waar oudere modellen nog 'domme' fouten maakten; code die helemaal niet uitvoerbaar was of meteen vastliep, zijn die fouten nu wel opgelost, bijvoorbeeld omdat LLMs speciaal voor code die zelf op de achtergrond runnen, kijken of het vastloopt en dan meteen om een aanpassing vragen. Maar omdat de overduidelijke fouten eruit zijn (better), zijn de fouten die overblijven nog lastiger te zien (worse):

They often generate code that fails to perform as intended, but which on the surface seems to run successfully, avoiding syntax errors or obvious crashes. It does this by removing safety checks, or by creating fake output that matches the desired format, or through a variety of other techniques to avoid crashing during execution.

Als je een beetje kan programmeren is het hele stuk van Triss echt de moeite waard, het vergelijkt in veel details generaties van verschillende modellen!

En dan nog even deze...

- Wat een homage aan Alex Pretti, een man wiens naam voor altijd verbonden zal zijn aan Trump 2 en ICE. Hartverscheurend.

- Sterke rapportage van AD over een geïmplodeerde kerosinetank op Schiphol in september die niet eerder in het nieuws was! Visueel mooi, echt een aanvulling op een gewone digitale versie van de krant.

- Goed verhaal over Sam Altman, zijn beloftes over wat openAI allemaal gaat oplossen (kanker, de huizencrisis, armoede, klimaatverandering, mentale gezondheid, democratie, hartziektes, gezondheidszorg, gratis energie, meer gelijkheid, en extreme rijkdom voor iedereen—en uit dit lijstje ontbreekt dan nog "natuurkunde"). Dit filmpje heeft niet alleen alle beloftes aan elkaar geplakt in een minuut of wat, maar gaat ook kort in op de voorgeschiedenis van andere (gefaalde) beloftes van Altman.

- Mooie visualisatie van Nature die in kaart brengt hoeveel onderzoeksgeld Trump geschrapt heeft in het eerste jaar van zijn tweede termijn en in welke vakgebieden (dankjewel aan mijn oud-promovendus Olivier voor de tip!)

Goed nieuws

Veel mensen zijn nu voorstanders van een verbod op social media onder de 16 jaar (63%) aldus de NOS. En, bijzonder, vooral onder zoomers (die zijn nu tussen de 16 en 28 jaar) groeit de steun van 44% vorig jaar tot 60% nu. En ja, er zijn allerhande problemen met een verbod onder jongeren, zoals dat volwassenen dan bewijs moeten gaan uploaden hoe oud ze zijn. Beter zou zijn om de kwalijke effecten te verbieden zoals endless scroll en een sterk algoritmische tijdlijn maar ik vind dit toch goed nieuws omdat het laat zien dat mensen, ook jongeren, heel goed snappen dat social media niet goed zijn zoals ze nu zijn.

Niet alleen Mamdani's winst in New York stemt positief, na deze fijne read over Sam Bigham van 23 die burgemeester werd van het stadje Carnegie bij Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania voel je je weer wat optimistischer over de levensvatbaarheid van de democratie.

In Frankrijk stoppen met ze Teams en Zoom, yeah! Helaas niet geheel en al met videobellen, dat was ook te mooi geweest, maar ze stappen over op een Frans alternatief meldt Tweakers.

Natuur is goed voor je, zelfs urban nature, maar zelfs zelfs... videos van de natuur.

Voor het eerst werden er meer elektrische auto's dan benzineauto's verkocht in de EU!

Slecht nieuws

Nederland zit vast aan de Amerikaanse cloud, aldus onderzoek van de NOS. Van de 16.500 onderzochte domeinnamen van Nederlandse overheden, zorginstellingen, scholen en vitale bedrijven worden gebruikt is maar liefst 67 procent aan een Amerikaanse clouddienst gekoppeld.

"Industrial-scale abuse", zo omschrijft New York Times wat er op Grok gebeurde, ik schreef er natuurlijk al eerder over, maar OMG:

In just nine days, Grok posted more than 4.4 million images. A review by The Times conservatively estimated that at least 41 percent of posts, or 1.8 million, most likely contained sexualized imagery of women

Absoluut gruwelijk onderzoek uit de VS over een dataset van 300.000 patienten. Nadat de totale abortus-ban inging in Texas, nam het aantal vrouwen dat na een miskraam een bloedtransfusie nodig had, mat 15% toe. Dat zijn dus voor het allergrootste gedeelte vrouwen die geen abortus wilden en desondanks door deze maatregel extra hebben moeten leiden, dus zelfs niet eens de categorie van mensen die de republieken vinden dat hun eigen leiden verdiend hebben. Maar ja, jammer joh, had je maar geen vrouw moeten worden.

AI detectie... dat werkt dus niet. Maar desondanks gebruiken universiteiten het wel (soms geïntegreerd in bestaande plagiaatscanners) en gebruiken studenten het om vooraf te kijken of hun eigen werk er wel door zou komen!

Weer een verhaal over een man die een einde aan zijn leven maakte na chatten met AI, het houdt maar niet op... Onderzoek van oa de universiteit van Denver laat zien dat juist kwetsbare jongeren—bijvoorbeeld omdat ze minder sterke familiebanden hebben—vaker kiezen voor een AI die zich persoonlijker voordoet ("first-person, affiliative, commitment language")

Events

- Vrijdag 6 februari kan je me zien in Theater ZIMIHC in Utrecht waar ik Theatergast ben!

- Zondag 8 februari ga ik in Artis het gesprek aan over AI.

- Dinsdag 10 februari kan je met mij meedoen met de boekenclub van Filosofie in Actie! We bespreken het boek De Grote Weigering van Marian Donner, maar dat hoef je vooraf niet te lezen.

- En op donderdag 12 februari eerst bij de NLT conferentie en dan bij NWO!

Geniet van je boterham, ik ga genieten van deze extra feestelijke week omdat ik woensdag jarig ben!

English

By popular demand... A short newsletter!

I'm really going to limit myself to two topics, so I will have enough time to work on my upcoming book. And of course, I was in the Volkskrant again this week with my regular column, this time about emancipation and student evaluations, so if you're short on Felienne, read that (only in Dutch, though)

EdTech, no, just no

It doesn't work!

Can't be a surprise to anyone reading this newsletter, of course. Last week, I quoted Thomas Edison—for those interested, here's a deep dive into the original sources of that quote—and this summer, I talked at length about the failures of the One Laptop Per Child project and the accompanying ideas of computer scientists. I'm going to devote an entire chapter to this in my book: how people who are crazy about technology themselves (I used to be one of them, by the way) think that all children will be the same once they have a laptop in their hands.

And although I know that it will never really penetrate mainstream thinking—we will always have Maurice de Honds who know nothing about education and yet start talking about innovation in schools because they are so conservative, the same for 100 years!—it seems that more people are beginning to understand the skepticism about this. Last week, for example, there was an article in The Economist—not exactly a magazine for left-leaning academics—about McPherson Middle School in Kansas, where they introduced a laptop program in 2022:

“We thought it was going to be really magical,” says Inge Esping, the principal. It wasn't. It “didn't really move the needle,” Ms. Esping says. Students found the program repetitive, rigid, and boring—and distraction proved irresistible once they were on their school-issued laptops.

That distraction does it every time! It's also my experience, as I wrote earlier (in Dutch), that as soon as you allow laptops in the classroom or lecture hall, you turn into a police officer who has to shout “no, not on YouTube” all the time, and that affects you and the class vibe. And this is not just an anecdote; they cite a meta-analysis from Stanford (a paper about other papers) that looked at 119 studies and what did they find?

found the studies described programmes that delivered at best only marginal gains on standardised tests. The majority had little effect, no effect or harmful ones.

Every single time. Sometimes I wonder why we keep trying, why is that myth so persistent? Kudos to the people at Khan Academy, who analyzed usage patterns of 200,000 users, and it's not really anything to write home about either. Yes, if you use it, your grades will go up. But... students don't do that:

24% of students have zero platform usage, 65% spend under 10 min per week (6 h per year), and only 10% meet KA's recommendations of 18 h a year (approximately 30 min per week).

That top 10% improves by 0.085 to 0.146 standard deviation, which is quite a lot, but that's really a small group of students who probably already enjoy practicing or are encouraged to do so at home. The average effect is only 0.031 standard deviation!

And who should ensure that it is used more? Yes, us teachers:

Teachers might reduce achievement gaps and boost overall gains by encouraging more productive use of the platform (focused on skill mastery)—especially among struggling students.

Jared Horvath, author of the book “The Digital Delusion”, also has his say in the Economist article: “In nearly every context, ed tech doesn't come close to the minimum threshold for meaningful learning impact.” In fact, children in schools with less technology often perform better, although the question is, of course, whether this is a causal relationship. It may also be that schools that are already struggling see technology as a solution. In any case, even if it doesn't have a negative result but simply none at all, it's pretty bizarre for something that costs schools $30 billion in the US alone ($165 billion worldwide). That money could have gone to schools instead, the article concludes dryly:

Back in 2013, Bill Gates remarked that it would take a decade to know whether education technology really worked.

More than ten years and hundreds of billions of dollars later, the answer is increasingly clear. Notes Emily Cherkin, an advocate and fed-up parent: “Imagine if all that money had gone into teachers instead.”

It's almost as if better learning isn't really the goal of tech companies... but, as NBC wrote this week about Google, getting kids young on their platforms so they remain lifelong customers:

One internal November 2020 presentation slide said acclimating children to Google's ecosystem in school would hopefully lead them to use its products as adults: “You get that loyalty early, and potentially for life.” Another undated slide deck suggested imagining a world where “Parents ask their children ‘Why aren't you watching more YouTube?’” and “School Administrators shift budgets from Textbooks to YouTube subscriptions.”

And, as the article in The Economist also emphasized, the result is often not nothing, but worse than nothing! It costs money that we could have spent elsewhere, it creates yet another public wave of criticism of teachers, but above all, students are the victims of technology that doesn't work. A very comprehensive report by the Brookings research institute concludes that "the risks of AI are not currently worth the benefits" The entire report is full of findings similar to those in the Economist article, so bookmark it and forward it to the optimists in your circle, but this sentence broke my heart:

AI is doing things for students that they used to enjoy.

Students, writes AI researcher Siri Beerends, deserve better (Dutch); they deserve us to put the brakes on their deskilling, but in most places the opposite is happening: AI is being embraced.

No wonder, perhaps, that students are staying away from education; at the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, attendance is now only 30%. According to Izaak Dekker, it's a three-stage process:

Students attend lectures much less than they used to. They read less thoroughly. And they make full use of artificial intelligence.

That may be easier, but it's not more fun! Of course, this applies not only to students, but to everyone. Yes, taking a test, writing a paper, preparing PowerPoint presentations, it's all a lot of work, but it was also nice when you managed to put something good together, or even something "okay" if you didn't have too much time. All those little moments of "yes, I did it" disappear when everything is done with AI. So it's embarrassing that VU as reported by nu.nl, which also interviewed me (Dutch) is conducting yet another experiment with an AI avatar for students to chat with.

Even boring work has its good points, as you can read in this brilliant paper by researchers from the French research institute Sciences Po, who conducted seven months of research among 32 participants, half of whom were students doing internships and the other half professionals, who were studied in great detail ("30 hours of group meetings, 8 hours of individual interviews, 400 pages of participants' written notes, and 600 LLM conversations"); a very good example of qualitative research that seeks to understand rather than measure.

And what does one of the participants say about automating boring tasks?

Before [using the LLM], I used to do those tasks already, I didn’t have more or less work. It just wasn't boring. I mean, I didn't think of it as something super interesting, but it wasn't boring either. And with the use of the LLM, it started to feel more and more boring. [...] It's not just that it revealed something [about my work], but somehow, the way we use it creates the boredom.

So why do we keep hearing these hallelujah stories? Perhaps this also has to do with the difference between the real workplace and the people who make decisions. The Maurice de Honds of this world talk to school principals, or in most cases to the boards of school foundations, which usually have dozens of schools affiliated with them. That's also something you only know if you work at a school yourself, and you can't really see it from the outside, even from a teacher training program: the extent to which the decisions made at schools are made by people who are distant from the schools, sometimes even people who have never taught in secondary education themselves.

And those people make the choices about technology, with little consultation with teachers about what they want, and of course they look very differently at the balance between opportunities and risks. In this survey of 5,000 American employees reported by the Wall Street Journal, you see a huge difference between what C-level executives think versus "normal peopple":

Better is worse!

Vibe coding, does it work and if so, for whom? A paper in Science examined 30 million GitHub commits (submitted pieces of code) from more than 150,000 programmers to see how many of them were written by AI. They did this with AI, so we should perhaps take the results with a grain of salt. They conclude that about 30% of all Python code in the US is now written with AI. They also looked at which programmers use AI and found that experienced programmers in particular have started writing more code (the authors call this a "productivity gain", but I don't buy that; more code isn't necessarily better, as every programmer knows). They also find, and I find this interesting, that experienced programmers are writing more new types of code, libraries they didn't know before ("exploration gains", fine). But they also write:

For less experienced programmers, we observe no meaningful increases in productivity or exploration.

Again, because they did not collect this data with a questionnaire or a plugin, it should be taken with a grain of salt. It could also be that novice programmers have learned to program in recent years based on a lot of AI code, so they also use that style manually. It's hard to say, but I do believe in the difference between beginners and experienced programmers, and that's interesting. Because how do those beginners gain the experience that leads to being able to make good use of those tools later in their careers? How do you learn to do more than just scan the output a little and simply ‘check in’, as it's called? I'm not the only one with this concern; the boss of one of the most widely used vibe coding tools, Cursor, says that:

“If you close your eyes and you don't look at the code and you have AIs build things with shaky foundations as you add another floor, and another floor, and another floor, and another floor, things start to kind of crumble,” he said.

And if this wasn't true before, it certainly is now, writes Jamie Triss in IEEE Spectrum, because the models are getting worse in his experience. And that's because of subtle differences.

As programmers we sometimes say "worse is better": meaning that software sometimes gets better (better) when it has fewer features (worse). And I found this to be very true. When I first started working on Hedy, we added a lot of cool features and options, but after a while, we removed many of these because the whole became cumbersome and confusing.

Here, the opposite seems to be true, namely "better is worse". Where older models still made 'stupid' mistakes, such as code that was completely unworkable or immediately crashed, those mistakes have now been resolved, for example because LLMs specifically designed for code that runs in the background check for crashes and immediately request adjustments.

But because the obvious errors have been removed (better), the remaining errors are even harder to spot (worse):

They often generate code that fails to perform as intended, but which on the surface seems to run successfully, avoiding syntax errors or obvious crashes. It does this by removing safety checks, or by creating fake output that matches the desired format, or through a variety of other techniques to avoid crashing during execution.

If you know a little bit about programming, Triss's entire piece is really worth reading, as it compares generations of different models in great detail!

And then there's this...

- What a tribute to Alex Pretti, a man whose name will forever be associated with Trump 2 and ICE. Heartbreaking.

- Strong reporting by AD about a kerosene tank that imploded at Schiphol Airport in September, which had not been in the news before! Visually beautiful, really complements a regular digital version of the newspaper.

- Good story about Sam Altman, his promises about what openAI is going to solve (cancer, the housing crisis, poverty, climate change, mental health, democracy, heart disease, healthcare, free energy, more equality, and extreme wealth for everyone—and this list is still missing "physics"). This video not only nicely combines all these promises, but also briefly discusses the history of Altman's other (failed) promises.

- Nice visualization by Nature that maps out how much research funding Trump has cut in the first year of his second term and in which fields (thanks to my former PhD student Olivier for the tip!).

Good news

Many people are now in favor of a ban on social media for those under 16 (63%), according to the NOS (Dutch). And, remarkably, support among zoomers (now between 16 and 28 years old) has grown from 44% last year to 60% now. And yes, there are all kinds of problems with a ban among young people, such as adults having to upload proof of their age. It would be better to ban the harmful effects, such as endless scrolling and a highly algorithmic timeline, but I still think this is good news because it shows that people, including young people, understand very well that social media is not good as it is now.

Not only is Mamdani's victory in New York encouraging, but after this enjoyable read about 23-year-old Sam Bigham, who became mayor of the town of Carnegie near Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania, you feel a little more optimistic about the viability of democracy.

The French will no longer be using Teams and Zoom. Unfortunately, they are not just stopping online meeting (would have been too good to be true) but they are switching to a French alternative, according to Tweakers (Dutch).

Nature is good for you, even urban nature, and even even... videos of nature.

For the first time, more electric cars than fossil fuel cars were sold in the EU.

Bad news

The Netherlands is stuck with the American cloud, according to research by the NOS (Dutch). Of the 16,500 domain names of Dutch government agencies, healthcare institutions, schools, and vital companies that were investigated, 67 percent are linked to an American cloud service.

"Industrial-scale abuse" is how the New York Times describes what happened on Grok. I wrote about it earlier, of course, but OMG:

In just nine days, Grok posted more than 4.4 million images. A review by The Times conservatively estimated that at least 41 percent of posts, or 1.8 million, most likely contained sexualized imagery of women

Absolutely horrifying research from the US on a dataset of 300,000 patients.After the total abortion ban went into effect in Texas, the number of women who needed a blood transfusion after a miscarriage increased by 15%. These are mostly women who did not want an abortion and nevertheless had to suffer extra because of this measure, so not even the category of people whom the republicans believe deserve their own suffering. But hey, too bad, you shouldn't have become a woman.

AI detection... doesn't work. But despite this, universities still use it (sometimes integrated into existing plagiarism scanners) and students use it to check in advance whether their own work would pass!

Another story about a man who ended his life after chatting with AI, it never ends... Research by the University of Denver, among others, shows that vulnerable young people—for example, because they have weaker family ties—are more likely to choose an AI that presents itself in a more personal way ("first-person, affiliative, commitment language").

Enjoy your sandwich! I'm going to enjoy this week, because it's my birthday on Wednesday!

Member discussion