AI in week 49

As always, go to /#english for the English version!

Waar ik de eerste paar dagen dat het Deltaplan echt boos en droevig was dat dit is wat mijn vakbroeders (en een enkele -zuster) met de wereld willen doen, ben ik nu op het punt dat ik erom kan lachen, met een column in Volkskrant over hoe schrijvers hun eigen plannen eigenlijk niet eens geloven. Het beste dat we kunnen doen tegen techbros, volgens Ed Zitron, is make fun of them.

Events

Alvast voor in de agenda voor na de kerstvakantie:

- 16 januari: Bij Onderwijsinzicht, georganiseerd door Kennisnet mag ik spreken over de impact van AI op leren. Ik gaf voorafgaand alvast een kort interview!

- 12 februari geef ik een keynote op NWO Insight Out, een congres voor vrouwen in de betawetenschappers (STEM) georganiseerd door NWO. Ik zal het daar (natuurlijk!) hebben over de beta-cultuur en het effect daarvan op hoe we werken en wat we onderzoeken in de wetenschap.

- 26 maart spreek ik op de Lerarendag Digitale Geletterdheid. Die dag proberen we leraren te ondersteunen bij het vormgeven van digitale geletterdheid op school.

Overpublicatie

Afgelopen vrijdag was ik te gast bij Spraakmakers, altijd erg leuk, en het onderwerp wat natuurlijk... AI. Maar deze keer heb ik het specifiek over de impact van AI op het doen van wetenschappelijk onderzoek gehad.

Zoals overal wordt AI ook in de wetenschap binnengehaald als de kip met de gouden eieren. Hoi, hoi, met AI kunnen we sneller meer kennis produceren, voor één wetenschapper betekende dat 113 papers in één jaar, waarvan 89 op dezelfde conferentie[[1]]!!! Zelfs als je standpunt dat je het moet omarmen en de uitvoer goed moet controleren, zoals dit weekend nog werd beargumenteerd in Nature, dan moet je je afvragen of dat op deze schaal mogelijk is. Zo moest Nature zelf onlangs een paper terugtrekken omdat er een overduidelijk met AI gegenereerde (en totaal niet kloppende) afbeelding instond. Peer reviewers hadden het niet gezien.

Maar meer nog, net als bij het onderwijs, moeten we ons eerst eens afvragen wat wetenschappelijk onderzoek is, en waartoe het dient, voor we goed kunnen bepalen of AI kan helpen.

Je denkt bij het schrijven van een paper misschien aan de ultieme vorm van kennisvergaring; data verzamelen over de wereld, theorieën ontwikkelen, historische analyses doen en zo steeds meer van de wereld gaan snappen. Dát is, natuurlijk, het doel van wetenschappelijke werk. Maar voor een individuele wetenschapper heeft een paper ook nog een ander doel: carrière maken. Ik sprak laatst een jonge wetenschapper in Nederland die om bevorderd te worden minstens 3 papers per jaar moet schrijven, al mag je dat wel middelen als je het ene jaar meer en daarna weer minder schrijft. Maar het blijft een numeriek doel, geen inhoudsdoel.

Het deed me denken aan het allereerste gesprek met mijn promotor. Is dat nou moeilijk, een proefschrift schrijven? Neehoor, zei hij, je schrijft gewoon 5 of 6 papers en dan ben je er wel. Wat voor papers dan? Top-papers, zei hij. En dat betekent niet dat je ze zelf top vindt, of dat ze echt impact hebben in de echte wereld, nee, dat betekent dat je ze naar "competitieve" conferenties stuurt [[1]] waar ze maar zo'n 10% van de papers accepteren. Zo'n conferentie, wordt vaak gezegd, is een soort loterij.

In 2014 deed AI conferentie NIPS (nu neurips geheten) een onderzoek waarbij ze een aantal papers door twee onafhankelijke commissies liet beoordelen, en dat bleek? Ze waren het niet eens over 57% van de geaccepteerde papers:

Most papers accepted by one committee were rejected by the other, and vice versa.

Dus, hadden ze alle papers nog een keer beoordeeld dan waren de meeste geaccepteerde papers niet uitgekozen. Laat dit even op je inwerken. De carrières van wetenschappers wordt gemaakt of gekraakt door een proces dat niet veel meer voorspellende waarde heeft dan een muntje opgooien.

Dat kan natuurlijk wel heel positief zijn voor de kwaliteit van de wetenschap he? Misschien zijn alle papers zo goed en schitterend dat de reviewers niet kunnen kiezen! Maar het is natuurlijk niet positief voor wetenschappers die mee moeten doen aan zo'n soort loterij. Want hoe win je de loterij? Door veel kaartjes te kopen!

Iedere promovendus voelt vanaf dag 1 de drang om te publiceren, publish or perish. De mensen die dat goed lukt, of die zich in die cultuur fijn en thuis voelen, die blijven, en wie dat niet lukt of niet fijn vindt, die haakt af. Onderzoek van VU-collega hoogleraar Klarita Gërxhani toont trouwens aan dat mannen in zo'n omgeving beter presteren dan vrouwen. Vrouwen presteren beter is een meer cooperatief landschap.

De wetenschap zit dus vol met mensen die erop gebrand zijn, en het vaak ook best leuk vinden, om zoveel mogelijk papers te schrijven, en daarmee hun individuele brand sterker te maken.

En ik neem dat individuele wetenschappers echt niet kwalijk, die moeten vaak vroeg in hun carrière op een tijdelijk contract laten zien dat ze echt tot de top behoren, terwijl ze ook nog les moeten geven, vaak precies in de fase met jonge kinderen zitten, en misschien ook nog willen sporten of andere hobbies ontplooien. Ik heb zelf al vaak genoeg verteld op verschillende plekken hoe rot ik mezelf voelde in de tijd dat ik nog op een tijdelijk contract van ZES JAAR zat (iets dat toen in geen enkele sector kon dan het hoger onderwijs, en gelukkig nu in Nederland ook niet meer), bijvoorbeeld ook in mijn oratie.

Het ligt niet aan die jonge wetenschappers zelf, het is een systeem dat slordigheid, opportunisme en regelrechte fraude in de hand werkt. In de zomer schreef ik nog over farmacoloog Szabo die allerhande gevallen van wetenschappelijke fraude verzamelde in zijn boek Unreliable. De voorbeelden zijn taltijk, in Nederland kennen we natuurlijk Diederik Stapel, en als je er nog meer wilt lezen kan je dus Unreliable lezen, of in het Nederlands het boek Sloppy Science van Stan van Pelt. Ik heb het nog niet gelezen, maar ik vermoed dat het lijkt op Unreliable van Szabo.

Recent speelde er ook weer en zeer pijnlijke case op MIT, zo schreef Wallstreet Journal waar een student economie een hele dataset verzonnen bleek te hebben. Uit zijn (dus niet bestaande) dataset zou blijken dat wetenschappers met een nieuwe AI tool veel sneller nieuwe kansrijke materialen kunnen vinden. Zijn professoren, waaronder nondeju een Nobelprijswinnaar (Daron Acemoglu), viel het helemaal niet op dat die data verzonnen was, ondanks dat het onderzoek naar eigen zeggen samen met een groot bedrijf was uitgevoerd; meer dan 1000 mensen zouden binnen dat ene bedrijf met deze AI tool gewerkt hebben. Dan moet je je als prof toch wel afvragen welk bedrijf dat is, en waarom die zomaar zouden samenwerken met een student. En wil je dan niet een keer mee, even koffiedrinken daar voor je eigen netwerk?

De fraude kwam pas aan het licht toen Charles Elkan, computerwetenschapper van de University of California mailde met vragen (trots deze keer op een vakbroeder!), want, zo zei hij, als een bedrijf zulke goede AI in huis heeft gehaald, dan zouden ze dat van de daken schreeuwen:

“If any company develops a software like this that is so valuable, they should be boasting about it,” he said in an interview.

Dat bedrijf dat moest volgens Elkan wel of 3M zijn of Corning, de enige twee die uberhaupt meer dan 1000 wetenschappers in dienst hebben die zo'n tool zouden kunnen gebruiken, het kon niet anders zo zei Elkan, of hij had hiervan gehoord als het zo was.

Hadden jullie dat dan niet eerder kunnen zien, vroeg The Wallstreet Journal in het lange stuk, je hebt toch wel verschillende versies van het paper meegelezen? Tsja, zei de Autor, de andere professor, ik heb geen commentaar maar “these are legitimate questions.” Het is een droevig verhaal, voor deze student, die niet meer aan MIT studeert, maar ook voor de wetenschap als geheel. Dit is waar we staan, iedereen wil zo veel mogelijk en zo spannend mogelijke doorbraken kunnen presenteren, blijkbaar geldt dat zelfs voor iemand die al een Nobelprijs heeft.

Nu denken jullie misschien weer, hela, wat heeft dit met AI te maken Hermans? Jaja, I am getting there. Want dít is de natte, rijke voedingsbodem waarop het zaadje van de AI kan ontkiemen. De enorme prestatiedruk in de wetenschap was de wereld al voor AI, en in die wereld komt nu AI de wetenschap in, met de belofte om sneller meer te kunnen gaan doen.

Stel je voor, het is lastig, maar doe toch even mee, dat wetenschappers onder geen enkele druk stonden om papers te schrijven. Natuurlijk wordt er in dat scenario wel verwacht dat wetenschappers íets doen, bijvoorbeeld dat je in overleg met de baas van je afdeling of vakgroep een mooie onderzoeksvraag opstelt en daar een jaar aan werkt. Ieder jaar in je voortgangsgesprek vertel je dan wat je hebt gedaan, soms is dat een hoop, soms misschien 5 mislukte experimenten die je niet kan publiceren als paper maar die wel kennis hebben opgeleverd. Misschien is dat wel een mooi onderwerp voor een podcast, of een leuke lezing of blogpost, want een ander zou er wel van kunnen leren, van die mislukkingen, in ieder geval om ze niet te herhalen. Als je echt de beste wetenschap wil doen met de meeste impact, zou je dan AI willen gebruiken om het sneller te doen?

Deze AI hype is voor mij het allermeest een dynamiek die overal (zorg, onderwijs, wetenschap, journalistiek) de echte problemen blootlegt. Mensen zeggen nu the quite part out loud.

Want de wens voor sneller meer wetenschap met AI legt zo goed bloot wat de motivatie is van mensen om papers te schrijven: het hebben van meer papers. Meer papers is een beter cv, is meer kans op meer beurzen, en dan dus weer meer kans op meer paper etc etc. Maar om wat te doen of te bereiken?

Sommige wetenschappers hebben ambities die er echt toe doen, denk aan het oplossen van honger in de wereld of het genezen van kanker. Laten we eens stilstaan bij dat laatste, kanker, wat heeft de wetenschap daar in de laatste jaren tegen gevonden. Nou, best wat revolutionairs: Iets waarmee je de kans op baarmoederhalskanker of een voorstadium bijna 90% verlaagt!

Jammer alleen dat dat "iets" een vaccin is, en ja, dat willen mensen niet meer nemen! Van de meisjes geboren tussen '97 en '10 is de vaccinatiegraad 60 tot 70 procent en bij jongens (die ook kanker kunnen krijgen van het virus, en het ook kunnen doorgeven) ligt dat percentage nog lager. Dus 30 tot 40 procent van de jonge meiden kiest ervoor om geen vaccin te nemen dat kanker kan voorkomen. En dat blijkt ook uit wie ziek wordt, van vrouwen die baarmoederhalskanker krijgen is slechts 15% gevaccineerd.

Dat belooft ook weinig goeds voor nieuwe vaccins in ontwikkeling, bijvoorbeeld tegen alvliesklierkanker.

En hoe komt dat nu? Dan komen we bij wat ook al bij Buitenhof zei, we hebben geen gebrek aan kennis.

Komt dat nu doordat we een gebrek hebben aan informatie over hoe goed een vaccin werkt tegen HPV? Nee. Ik weet dat er een een hele waaier aan oorzaken is, maar ik noem er hier twee.

- We hebben een gebrek aan onderzoek over hoe we zulke kennis goed in de wereld brengen. Sociale en geesteswetenschappen staan overal, ook in Nederland, al jaren onder druk en worden lang niet altijd serieus genomen. Denk maar aan de coronacrisis. Toen luisterden we naar longartsen en epidemiologen (belangrijk!) maar ontbraken in het crisisteam sociologen, pedagogen en epistemologen, en juist hun kennis had misschien wel kunnen helpen om mensen toen en nu minder vaccinsceptisch te maken. Hoe verstandig het misschien ook was van de overheid om vaccinaties te verplichten, mogelijk heeft dit op de lange termijn toch het effect gehad dat mensen vaccins anders zijn gaan zien, en dat had veel beter gekund.

- Er is geen gebrek aan droge, abstracte kennis of informatie, maar een gebrek aan goede mooie verhalen, vertalingen naar de praktijk. We lijden, zei ik bij Piek Knijff in de podcast in het voorjaar niet zozeer onder desinformatie, maar onder desverhalen. Het verhaal "je lichaam kan zelf een infectie wel aan" heeft het blijkbaar gewonnen van "je kan zo vreselijk ziek worden als je dit niet doet, het is de moeite waard" (zie ook weer de afgrijselijke rapportage van Volkskrant over long covid, deze week).

De andere kant van "kamp vaccin", in Amerika verpersoonlijkt door RFK junior, haalt alles uit de kast, zo bleek deze week uit een long read van New York Times. Het tekent een al twee decennia onuitputtelijke kruistocht op, gestart met een overtuiging dat kwik in vaccins autisme veroorzaakt.

Dat is dus waar wetenschappers tegenin moeten oreren, en wij hebben ook verhalen nodig over wetenschap, zoals de hartverscheurende brief van Roald Dahl over het verliezen van zijn twaalfjarige dochter.

Ook het schitterend essay dat dit jaar de Robbert Dijkgraafprijs won, adresseerde het probleem van niet luisteren naar kennis, door schrijfster Jade Hurenkamp, student Oudheidswetenschappen aan de UvA, Oost-Indisch weten genoemd.

Als wetenschappers willen dat we wereld beter wordt, moeten ze hun taak in de maatschappij serieus gaan nemen en dat betekent meer vertellen over wetenschap, en minder 'wetenschap doen'. Of, beter nog de taak van de wetenschapper herkaderen, en dit soort werkzaamheden als de kern gaan zien.

Sommige lezers vragen mij wel eens hoe ik in godsnaam tijd "overhoud" om in deze nieuwsbrief te steken, maar ik zie dit juist als het voornaamste onderdeel van mijn werk, het is niet iets dat ik ernaast doe, het is wat ik doe. Ik neem het dus jonge wetenschappers niet kwalijk dat zij meedoen aan de ratrace omdat ze vrezen dat ze anders geen baan meer hebben. Maar ik neem het senior wetenschappers wel kwalijk. Die kunnen zich zonder veel carrièreschade los maken van het hamsterrad, en bovendien hebben die de macht om systemen te veranderen, althans meer dan jonge mensen. Wat mij het allermeeste is tegengevallen van "oud worden" in de wetenschap is dat de mensen waarmee ik in mijn jonge jaren plannetjes smeedde voor het veranderen van het systeem, nu opeens niet thuis geven, omdat ze bijvoorbeeld toch nog wel even wat onderzoeksgeld willen binnenharken voor ze echt openlijk in verzet komen.

"Zo'n column schrijven zoals jij in het voorjaar deed," zei een oud-collega tegen mij–doelend op een column in Volkskrant waarin ik betoogde dat ik de wetenschap helemaal niet wil veranderen—"dat zou ik nooit doen. Dan krijg je nooit meer een beurs van NWO". Nou lijkt het mij uiterst onwaarschijnlijk dat mijn kansen bij NWO afhangen van wat ik in de krant schrijf, maar dit geeft wel aan wat de prioriteit is van deze persoon, en dat is niet de wetenschap verbeteren.

En dan zal de AI optimist zeggen: maar Felienne, door AI gaan we tijd overhouden voor kennisdeling! Met AI schrijf je een paper in de helft van de tijd en dan gaan we daarna de wetenschap verbreden, onze kennis delen in de krant en op tv, en in debat in het buurthuis!

Maar, dat is om een aantal redenen heel erg onwaarschijnlijk. En dan bedoel ik niet eens dat het maar de vraag is of AI echt tijd bespaart, zoals onlangs bleek uit onderzoek van bijvoorbeeld Neil Selwyn.

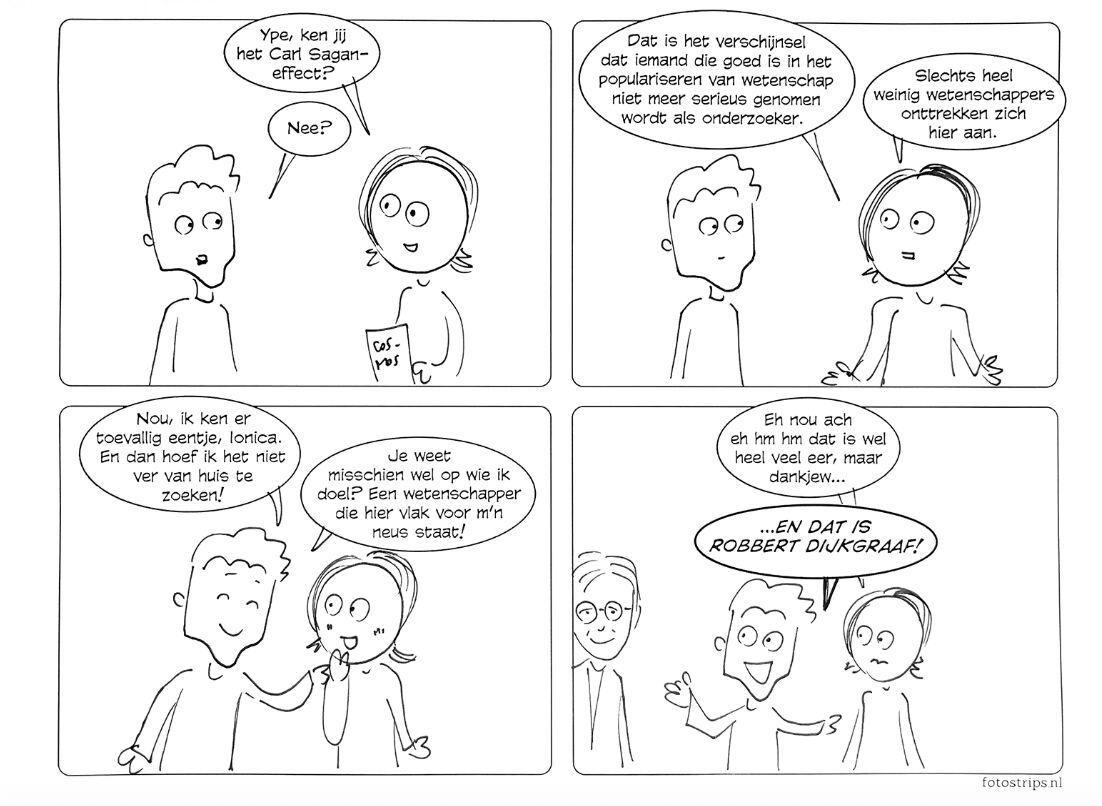

Ik bedoel veel eerder dat in de wereld waarin er AI is, worden communicatie-taken nog steeds niet beloond. Je leidinggevende kijkt er niet naar, en je collega-wetenschappers gaan je helaas niet serieuzer maar juist minder serieus nemen, het Sagan effect. Dus waarom zou je wetenschapscommunicatie doen als je ook gewoon twee papers kan schrijven in dezelfde tijd?

Wetenschappers die we nu als universiteiten werven willen niet alleen geen wetenschapscommunicatie doen, ze kunnen het ook niet. Of ja, als ze het kunnen dan is dat toevallig zo, het is geen eigenschap waar over het algemeen naar gekeken wordt als je ergens wordt aangenomen.

En, als allerlaatste argument is er nog de vraag hoe we, als we met AI zo vreselijk veel papers kunnen schrijven, wie die dan gaat lezen. En dan zeggen de optimisten weer dat AI dat allemaal voor ons kan samenvatten en dat we dan alleen maar die samenvattingen hoeven te lezen. Maar leidt dat dan tot meer kennis? Het klinkt paradoxaal maar ik denk dat er op die manier minder kennis in de wereld komt. Want, kennis opdoen gaat niet alleen over feitjes weten, maar ook over bereid zijn om de kennis die je opdoet te verdedigen. Ik citeerde een paar weken geleden nog Peter Naur's paper Programming As Theory Building, die zegt dat als je ergens over nadenkt, je dan ook een theorie maakt in je brein. Een theorie betekent bij hem:

the knowledge a person must have in order not only to do certain things intelligently but also to explain them, to answer queries about them, to argue about them, and so forth.

Door ergens actief over na te denken (Naur betrekt dit op programmeren) ontwikkel je een theorie, en kan je dus niet alleen uitleggen wat er staat, maar ook waarom.

Ironisch genoeg is Naur's paper een mooi voorbeeld van wetenschapscommunicatie, want hij schrijft hier niet zozeer over zijn eigen werk, maar vertaalt vooral werk uit de cognitiewetenschap van filosoof Gilbert Ryle naar een informatica-publiek, en kende ik dit werk van hem niet, maar wel al zijn technische werk naar het maken van programmeertalen.

Volgens de theorie van Naur, die ik ook totaal aanhang, is het soort kennis dat je opdoet als je alleen samenvattingen leest, heel anders dan de kennis die je opdoet als je op de een of andere manier actief met een onderwerp bezig bent. En alleen dat soort kennis kan je dan ook uitleggen, verdedigen en bediscussieren, precies die activiteiten die nodig zijn voor het communiceren van wetenschap.

[[1]]: In tegenstelling tot alle andere vakgebieden publiceren informatici voornamelijk in proceedings (verslagen) van conferenties. Andere wetenschappers publiceren vooral in journals (tijdschriften).

AI denkt niet

Door al dat Deltaplangedoe de afgelopen twee weken helemaal geen ruimte meer gehad voor een heel fijn verhaal van Rens Bod in Trouw, dat hij origineel schreef als reactie op mijn stuk in Trouw en paar weken terug dat ik mocht voorlezen bij de uitreiking van de prijs voor de onderwijsjournalistiek. AI, zo zegt Bod, denkt helemaal niet, en we moeten studenten dat vertellen.

Rens Bod is trouwens niet de enige die dit zegt, in the Verge konden we vorige week een hele fijne samenvatting lezen van een opiniestuk uit Nature getiteld Language is primarily a tool for communication rather than thought. Dat zeer leesbare stuk onderbouwt heel fijn dat zowel "taal is nodig om te denken" en "denken is nodig om taal te produceren" niet aantoonbaar juist zijn, en dat een model alleen gebouwd op taal niet als denken geclassificeerd mag worden. Dus once more for the people in the back: een LLM denkt niet.

Bod is trouwens enorm positief want hij zegt dat we door AI misschien "iets van de eeuwenoude humanistische traditie" kunnen terugwinnen:

Als we teruggaan naar die traditie van kritisch denken, is de AI-revolutie een verborgen zegen: dankzij generatieve AI gaan we de aloude humanistische waarheidsvinding opnieuw waarderen.

Ik hoop dat hij gelijk heeft! Als schrijver merk ik dit effect zeker, ik ben de afgelopen maanden veel preciezer geworden in het citeren van bronnen. Vroeger vertrouwde ik wat ik online las, nu controleer is alles. Nou is dat geen zegen hoor, het haalt de lol uit lezen, maar het zorgt er wel voor dat ikzelf veel secuurder ben gaan citeren, en ik geef toe, dat is winst.

En het lijkt erop dat een focus op langzaam en precies in de collegezaal ook kan werken, las ik in een heel uplifting stuk in New York Times Magazine. Hij zegt dat we moeten praten over wat AI ons verleidt te doen:

You can’t address A.I.’s effect on writing without considering its invitation to settle for a summary of content instead of actually reading.

Ja, de lokroep van sneller meer lezen, met minder aandacht voor detail, en met natuurlijk veel minder blootstelling aan rijke tekst en dus vocabulaire. Daartoe moet je je verhouden. In plaats dus van je vakken AI-proof maken met strenge controle, kan je beter een AI resistente aanpak gebruiken, zegt Carlo Rotella, docent Engels aan Boston College:

An A.I.-resistant English course has three main elements: pen-and-paper and oral testing; teaching the process of writing rather than just assigning papers; and greater emphasis on what happens in the classroom.

Dit lijkt me allemaal verstandige voorstellen, verstandiger dan wat de VU voorstelt in hun (ik weiger onze te zeggen) AI-geletterdheid Companion, waarin "Leerondersteunend gebruik" wordt beschreven hoe je AI kan inzetten als je vastloopt.

Je hebt een uitdagende onderzoeksopdracht gekregen, maar je hoofd zit vol losse ideeën en je weet niet goed waar je moet beginnen. In plaats van in paniek eindeloos te scrollen door bronnen of blanco naar je scherm te staren, open je een generatieve AI-tool zoals ChatGPT. Je voert een gerichte prompt in met jouw losse ideeën erbij: "Stel je bent een milieujurist. Geef me drie perspectieven over de juridische gevolgen van microplastics in Europese wetgeving." Er verschijnen bruikbare invalshoeken, suggesties voor bronnen en een voorstel voor structuur. Je herschrijft, reflecteert, zoekt verder, schrapt, voegt nieuwe onderdelen toe, maar die eerste stap, die is gezet. AI werkt voor jou, niet andersom.

Het is echt woestmakend dat juist deze worsteling, waarvan je zoveel kan leren als je die met studenten bespreekbaar maakt, weggepoetst moet worden, en dat een student zijn eigen ideeën nooit naar boven kunnen komen omdat ze bij het idee van AI beginnen en ze vanaf daar alleen nog maar hoeven te schrappen en toevoegen. Je ziet hier tussen de regels een absolute focus op het product, dat moet goed worden, en daar moet je dan maar AI voor gebruiken, want een leeg velletje inleveren, dat kan niet.

Het leerproces van de student wordt zo door technologie totaal aan het zicht onttrokken, ik kan niet meer zien of een student een mooi stuk zelf geschreven heeft, of uit AI gehaald heeft of iets ertussen in. Hoe moet ik dan beoordelen hoe hij het doet?

Onder het mom van studenten klaarstomen voor de toekomst worden hier keuzes gemaakt over hoe ik les moet geven, en wat ik wel of niet wil zien van een student. Het proces van de worsteling wordt tegen mijn zin in aan mijn zicht onttrokken. En die macht komt dan, zo zei ik ook al bij de Jonge Akademia podcast, te liggen bij een (hoogstwaarschijnlijk Amerikaans) bedrijf.

Hoogleraar Michael Clune van Ohio State University noemde dit soort plannen in The Atlantic weinig subtiel de "zelf-lobotomie" van universiteiten:

such policies represent a dangerously hasty and uninformed response to the technology. Based on the available evidence, the skills that future graduates will most need in the AI era—creative thinking, the capacity to learn new things, flexible modes of analysis—are precisely those that are likely to be eroded by inserting AI into the educational process.

Precies, er is geen enkel bewijs dat dit gebruik van AI het leerproces ten goede komt, en ik doe in mijn lessen van ook het tegenovergestelde, en stel juist het proces centraal zet. Ik deed dat met labour-based grading, waarbij mijn studenten gedurende het semester drie keer een draft mochten inleveren, en als ze dat deden gegarandeerd een voldoende kregen. Het maakte me niets uit wat ze inleverden, ik oordeelde niet maar gaf wel feedback. Spelfouten, rommelige overdenkingen, de losse ideeën die in je hoofd zetten, werkelijk alles was mij best, en het was heerlijk! Studenten vonden het bevrijdend en ik eerlijk gezegd ook. In veel gevallen, zeiden de studenten, hielp het feit dat ze wisten dat ik niet zou oordelen al met iets op papier krijgen.

Je kan beter aandacht aan ze besteden als ze nog bezig zijn, dan na het semester als ze alleen nog om het cijfer geven, citeert Rotella zijn collega Maia McAleavey.

En dat werkt, onderschrijft Rotella ook.

it has come as a pleasant surprise to me and to many of my fellow teachers that the A.I. apocalypse that was expected to arrive in full force in higher education this fall, bringing an end to reading and writing and school as we know them, has not come to pass just yet. Responding to the rise of A.I. by doubling down on the humanity of the humanities appears to be working, at least for the moment.

Het hele stuk zit vol met werkelijk heerlijke AI resistente lessuggesties, zoals vijfminutenquizzen met vragen over hele gekke details, zoals wat Anna's zoon in Anna Karenina als verjaardagscadeau kreeg in 1875, of studenten vragen om hun handgeschreven aantekeningen in te leveren zodat hij ze kan "zien denken".

Maar Rotella ziet ook de grote lijnen, in zijn oproep om te benadrukken hoe bijzonder het eigenlijk is om met een groep mensen bij elkaar te komen en een stuk echt diep te lezen en met elkaar te bediscussiëren. Zoiets doe je waarschijnlijk nooit meer in je leven, dus geniet er nu maar van.

This tech-obsessed moment may have finally pushed humanists to identify the value of their disciplines and play to their strengths, after first going fetal for far too long when assailed by return-on-investment literalists who willfully misunderstand the fit between school and work (“There is no job called English or history”).

Ja, misschien is deze AI hype wel een blessing in disguise en zien we in dat universiteiten zich veel te lang hebben laten gijzelen door het arbeidsmarktperspectief. Een mens mag dromen, toch?

The end of undertitleing?

In week 36 had ik het nog over het onverdeeld positieve effect van ondertiteling op de Engelse taalvaardigheid van Nederlander, en schreef daarbij "Wel jammer dat AI al die ondertitelingen onleesbaar gaat maken", niet wetende hoe snel het zou gaan. Want, zo las ik op een LinkedIn post van Piek Knijff, er zijn blijkbaar al Engelstalige series die met AI Nederlands nasynchroniseren.

Blegh! Niet alleen het argument van Piek is valide, dat kinderen zo totaal wennen aan neppe taal van neppe mensen, maar zo missen we ook nog eens gratis een hele standaarddeviatie beter zijn in Engels; een zeldzaam voorbeeld van hoe leren met echt heel weinig expliciete moeite kan gebeuren. Nu zullen de echte AI fans natuurlijk zeggen dat we binnenkort helemaal geen Engels meer hoeven te kunnen, omdat we een babelfish dragen..., maar dat even terzijde.

Wat nu op tv gebeurt, komt straks ongetwijfeld ook op YouTube en Tiktok, de plekken waar jongeren natuurlijk ook Engels leren, want alle techbedrijven zoeken plekken om AI in te zetten.

Het voorspelbare resultaat is dat Nederlandse jongeren straks minder goed Engels spreken, en wie is daar de verantwoordelijke voor? Waar in de oude wereld de omroepen als gatekeepers bepaalden wat we te zien krijgen, en hoe (wat natuurlijk ook allerhande problemen veroorzaakte!) bepaalt nu een product owner bij een groot software bedrijf in Amerika, iemand die naar alle waarschijnlijkheid niet eens tweetalig is, of bekend met onderzoek waaruit de voordelen van ondertiteling blijken, wat en hoe Nederlandse burgers kijken.

De alomtegenwoordigheid van AI kent talloze problemen, maar een ervan is het langzame verschuiven van besluiten die vroeger lagen bij mensen dicht op het vuur; een omroep over de taal van programma's, een dokter over hoe hij omging met patiënten, een leraar die steeds keuzes maakte over leerlingen, weg van die kenners. Precies daar waar het ertoe doet, maken nu bedrijven de dienst uit.

De lezersvraag: hoe is je nieuwsbrief anders dan een paper, of een tweet?

Ik pak ook nog even een lezersvraag mee. I know, ik heb er echt nog een dozijn in de wachtrij, sorry als ik nog niet aan jouwe ben toegekomen *something something deltaplan*. Deze vond ik echt heel erg leuk, iemand vroeg me hoe het schrijven van mijn nieuwsbrief zich verhoudt tot mijn eerdere werk, zowel mijn hoogtijdagen op Twitter [[2]] als het schrijven van papers.

Ik ben echt aan mijn nieuwsbrief begonnen omdat ik Twitter zo miste, ik heb 10 jaar lang nieuws gelezen en bij alles gedacht: hier heb ik ook een mening over, en hop online, en ik merkte dat mijn gedachten gewoon over elkaar heen bleven buitelen zonder uitlaatklep. Dus wat dat betreft vult een nieuwsbrief voor mij wel de rol van tweets.

Twee dingen vind ik tot nu toe echt heel erg leuk aan mijn nieuwsbrief, vergeleken met andere uitlaatkleppen.

Ten eerste is het heerlijk om op onderwerpen terug te kunnen komen. Op Twitter refereerde je zelden terug naar een tweet van weken terug, dat paste gewoon niet bij waar het voor was. Zoals McLuhan schrijft in het heerlijke Amusing ourselves to death:

...consider the primitive technology of smoke signals. While I do not know exactly what content was once carried in the smoke signals of American Indians [sic], I can safely guess that it did not include philosophical argument. Puffs of smoke are insufficiently complex to express ideas on the nature of existence…. You cannot use smoke to do philosophy. Its form excludes its content.

Steeds terugkomen op stukken—"zoals ik eerder al schreef" is vast de meestgebruikte tekst hier—zorgt ervoor dat ik dieper kan nadenken over onderwerpen en beter onthoud waarover ik zelf heb geschreven [[3]] .

Wat ik verder nog heerlijk vind ik dat ik kan schrijven zoals ik lees. Ik heb de afgelopen jaren enorm genoten van goede non-fictie en wetenschappelijke werk uit de etnografie, filosofie en feministische theorie. David Graeber, Mary Midgley, Mary Beard, heerlijk allemaal! Daarin worden vaak hele mooie verhaallijnen onderbouwd met termen, ideeën en verhalen uit andere boeken. Dat soort teksten las ik tijdens mijn promotie niet, alleen papers waarin experimenten beschreven werden en de uitkomsten ervan, en wat je niet kent, kan je ook niet willen worden.

Maar nu ik dit soort teksten lees, voel ik dat mijn brein ook zó werkt; ik werk mijn gedachtes uit en terwijl ik dat doe denk ik: zus en zo schreef daar ook over, even mijn aantekeningen erbij zoeken en een goede aansluiting maken. Het voelt als thuiskomen na een lange vakantie.

[[2]]: Vermoedelijk zal ik nooit meer ergens 16.000 followers hebben 😭! Wil je mijn pijn verzachten, stuur deze nieuwsbrief eens naar iemand door, zodat ik misschien ooit de 5000 abonnees aantik. Dat lijkt me al een heel aardig doel!

[[3]]: Ik word hierbij trouwens geholpen door het feit dat mijn nieuwsbriefplatform gekoppeld is aan Obsidian waardoor ik alles heel makkelijk kan doorzoeken en snel kan linken aan oudere posts.

Goed nieuws

De tentoonstelling Alice and Eve, waarin 30 vrouwelijke informatica-wetenschappers in de spotlight gezet worden om te laten zien dat ook wij vrouwen aan de informatica bijdragen heeft een prijs gewonnen (en ik ben een van die 30, is dat niet cool?!)

En dan ook wat goed nieuws, maar niet voor jou en mij. Congresleden in de VS die leiderschapsrollen gaan vervullen, verdienen daarna 47 procentpunten meer dan andere politici. Dat komt volgens de studie oa omdat ze handelen in aandelen die later grote contracten krijgen!

Dankzij held Bert Hubert is de AIVD gestopt met Google Analytics op vacatures, en dat nieuws bereikte zelfs de internationale media! Hele terecht want misschien is het in dit geopolitieke klimaat niet zo handig als de VS weet wie onze toekomstige spionnen worden.

Slecht nieuws

Zomergasten stopt. Nou, daar gaat mijn allergrootste droom om nog ooit zomergast te worden. Pestbezuiniging noemde Joris Luyendijk het heel terecht in NRC. Met ook de quote (van Telegraaf-columnist Rob Hoogland): "Ik ben niet rechts, ik heb gewoon een bloedhekel aan links". Ik denk dat we aan de verkiezingen en de aanhoudende weigering van VVD precies kunnen zien hoe waar dat is.

De Nederlandse overheid maakt steeds meer gebruik van generatieve AI, zo onderzocht TNO en schreef NRC. Dit roept vragen op "over de controle, veiligheid en digitale onafhankelijkheid" omdat die modellen vaak Amerikaanse software gebruiken. Ook vriendin van de nieuwsbrief Wiep Hamstra liet zich in Volkskrant kritisch uit over de bevindingen van TNO:

Terwijl we medicijnen eerst uitvoerig testen onder gecontroleerde omstandigheden, vinden de experimenten met AI midden in de maatschappij plaats.

Carnegie Mellon becijfert dat in Amerika stroomtarieven in 2030 8% gaan stijgen door meer data centra op het stroomnet, en het minen van crypto.

En dan, volgens een lek gaat chatGPT binnenkort ads laten zien, en sommige gebruikers hebben die ook al te zien gekregen, ook al werd het door openAI ook al weer snel tegengesproken. Hoe het ook zij, openAI heeft een verdienmodel nodig, het feest is wel voorbij, zo schreef Laurens Verhagen afgelopen weekend in Volkskrant, dus als het geen ads zijn, dan wel wat anders.

Geniet van je boterham!

English

In the first few days of the Delta Plan I was really angry and sad that this is what my fellow computer people want to do to the world, I am now at the point where I can laugh about it, with a column in Volkskrant about how writers don't even believe in their own plans. The best thing we can do against tech bros, according to Ed Zitron, is make fun of them.

Events

Mark your calendars for after the Christmas break:

- January 16: At Onderwijsinzicht, organized by Kennisnet, I will be speaking about the impact of AI on learning. I gave a short interview about it!

- February 12: I will give a keynote speech at NWO Insight Out, a conference for women in science (STEM) organized by NWO. I will (of course!) talk about the culture of science and its effect on how we work and what we research in science. This talk will be in English, by the way.

- On March 26, I will speak at the Teachers' Day Digital Literacy. On that day, we will try to support teachers in shaping digital literacy at school.

Overpublication

Last Friday, I was a guest on Spraakmakers, which is always great fun, and the topic was, of course... AI. But this time, I specifically talked about the impact of AI on scientific research (in Dutch).

As in many domains, AI is also being welcomed as the goose that with the golden eggs; so we can produce more knowledge faster. For one scientist, AI writing meant 113 papers in one year, 89 of which were at the same conference[[11]]!!! Even if you take the position that we should embrace it and carefully monitor its output, as was argued this weekend in Nature, you have to ask yourself whether that is possible on this scale. For example, Nature itself recently had to withdraw a paper because it contained an obviously AI-generated (and completely inaccurate) image. Peer reviewers had not noticed it.

But more importantly, as with education, we must first ask ourselves what scientific research is and what its purpose is before we can properly determine whether AI can help.

When writing a paper, you might think of it as the ultimate form of knowledge gathering: collecting data about the world, developing theories, conducting historical analyses, and thus gaining a greater understanding of the world. That is, of course, the goal of scientific work. But for an individual scientist, a paper also has another purpose: advancing their career. I recently spoke to a young scientist in the Netherlands who has to write at least three papers a year to get promoted, although you can average it out if you write more one year and less the next. But it remains a numerical goal, not a content goal.

It reminded me of my very first conversation with my supervisor. Is it difficult to write a dissertation? No, he said, you just write five or six papers and you're done. What kind of papers? "Top-rated papers", he said. And that doesn't mean that you think they're solid, or that they really have an impact in the real world, no, it means that you send them to "competitive" conferences [[11]] where only about 10% of the papers are accepted.

Such a conference however, it is often said, is a kind of lottery. In 2014, the AI conference NIPS (now called Neurips) conducted a study in which they had a number of papers reviewed by two independent committees, and what did they find? They disagreed on 57% of the accepted papers:

Most papers accepted by one committee were rejected by the other, and vice versa.

So, if they had reviewed all the papers again, most of the accepted papers would not have been selected. Let that sink in for a moment. The careers of scientists are made or broken by a process that has little more predictive value than flipping a coin.

Of course, this could be positive for the quality of science, right? Maybe all the papers are so good and brilliant that the reviewers can't choose! But it's obviously not positive for scientists who have to participate in this kind of lottery. Because how do you win the lottery? By buying lots of tickets!

From day one, every PhD student feels the urge to publish, publish or perish. Those who succeed in doing so, or who feel comfortable and at home in that culture, stay, and those who don't succeed or don't like it drop out. Research by VU colleague Professor Klarita Gërxhani shows that men perform better than women in such an environment. Women perform better in a more cooperative landscape.

So science is full of people who are eager, and often quite enjoy, writing as many papers as possible, thereby strengthening their individual brand.

And I really don't blame individual scientists for that. Early in their careers, they often have to prove that they really belong at the top on a temporary contract, while also having to teach, often while their children are young, and perhaps also wanting to play sports or pursue other hobbies. I have often enough said in various places how awful I felt when I was still on a SIX-YEAR temporary contract (something that was only possible in higher education at the time, and fortunately is no longer the case in the Netherlands), for example in my inaugural lecture (in Dutch).

It is not the fault of these young scientists themselves; it is a system that encourages sloppiness, opportunism, and outright fraud. In the summer, I wrote about pharmacologist Szabo, who collected all kinds of cases of scientific fraud in his book Unreliable. There are countless examples. In the Netherlands, we immediately think of Diederik Stapel, and if you want to read more, you can read Unreliable.

Recently, there was another very painful case at MIT, as reported by the Wall Street Journal, where an economics student turned out to have fabricated an entire dataset. His (non-existent) dataset allegedly showed that scientists could find promising new materials much faster with a new AI tool. His professors, including a Nobel Prize winner (Daron Acemoglu), did not notice that the data was fake, even though the research was supposedly conducted in collaboration with a large company; more than 1,000 people within that company were said to have worked with this AI tool. As a professor, you have to wonder which company that is and why they would collaborate with a student just like that. And wouldn't you want to go along for a coffee?

The fraud only came to light when Charles Elkan, a computer scientist at the University of California, sent an email with questions (proudly to a colleague this time!), because, he said, if a company had acquired such good AI, they would be shouting it from the rooftops:

“If any company develops software like this that is so valuable, they should be boasting about it,” he said in an interview.

According to Elkan, that company had to be either 3M or Corning, the only two that employ more than 1,000 scientists who could use such a tool. It couldn't be otherwise, Elkan said, or he would have heard about it if that were the case.

Couldn't you have seen that earlier, asked The Wall Street Journal in its long article, since you had read several versions of the paper? Well, said the Autor, the other professor, I have no comment, but "these are legitimate questions." It's a sad story, not only for this student, who is no longer studying at MIT, but also for science as a whole. This is where we stand: everyone wants to present as many exciting breakthroughs as possible, apparently even someone who already has a Nobel Prize.

Now you may be thinking, hey, what does this have to do with AI, Hermans? Yes, yes, I'm getting there. Because this is the rich, fertile ground in which the seed of AI can germinate. The enormous pressure to perform in science already existed before AI, and now AI is entering that world, with the promise of being able to do more, faster.

Imagine, it's difficult, but go along with it for a moment, that scientists were under no pressure whatsoever to write papers. Of course, in that scenario, scientists are still expected to do something, for example, to formulate an interesting research question in consultation with the head of your department or faculty and work on it for a year. Every year in your progress review, you would report on what you have done. Sometimes that would be a lot, sometimes perhaps five failed experiments that you cannot publish as a paper but which have yielded knowledge. Maybe that would be a good topic for a podcast, or an interesting lecture or blog post, because others could learn from those failures, at least to not repeat them. If you really want to do the best science with the most impact, would you want to use AI to do it faster?

For me, this AI hype is most of all a dynamic that exposes the real problems everywhere (healthcare, education, science, journalism). People are now saying the quiet part out loud.

Because the desire for faster, more science with AI exposes so well what motivates people to write papers: having more papers. More papers means a better resume, a better chance of more grants, and then again a better chance of more papers, etc., etc. But to do or achieve what?

Some scientists have ambitions that really matter, such as solving world hunger or curing cancer. Let's consider the latter, cancer. What has science found in recent years to combat it? Well, quite a few revolutionary things: something that reduces the risk of cervical cancer by almost 90%!

It's just a shame that that "something" is a vaccine, and yes, people don't want to take it anymore! Among girls born between 1997 and 2010, the vaccination rate is 60 to 70 percent, and among boys (who can also get cancer from the virus and pass it on), that percentage is even lower. So 30 to 40 percent of young girls choose not to take a vaccine that can prevent cancer. And this is also evident from who gets sick: of women who get cervical cancer, only 15% have been vaccinated (Dutch).

This does not bode well for new vaccines in development, such as those against pancreatic cancer.

And why is that? This brings us to I said at Buitenhof also: we do not lack knowledge.

Is this because we lack information about how well a vaccine works against HPV? No. I know there are a whole range of causes, but I will mention two here.

- We lack research into how to effectively disseminate such knowledge. Social sciences and humanities have been under pressure for years, including in the Netherlands, and are not always taken seriously. Just think of the coronavirus crisis. We listened to pulmonologists and epidemiologists (important!), but the crisis team lacked sociologists, educators, and epistemologists, and it was precisely their knowledge that could have helped to make people less skeptical about vaccines then and now. However wise it may have been for the government to make vaccinations mandatory, in the long term this may have had the effect of changing people's perception of vaccines, and that could have been handled much better.

- There is no lack of dry, abstract knowledge or information, but a lack of good, compelling stories, translations into practice. As I said to Piek Knijff in her podcast in the spring, we suffer not so much from misinformation as from misstories. The narrative "your body can handle an infection on its own" has apparently won out over "you can get incredibly ill if you don't do this, it's worth it" (see also the horrifying report in De Volkskrant about long COVID this week (in Dutch)).

The other side of vaccine debate personified in America by RFK junior, is pulling out all the stops, as this week's long read in the New York Times revealed. It chronicles a two-decade-long crusade, started with the belief that mercury in vaccines causes autism.

That is what scientists have to argue against, and we also need stories about science, such as the heartbreaking letter from Roald Dahl about losing his twelve-year-old daughter.

The brilliant essay that won this year's Robbert Dijkgraaf Prize, written by Jade Hurenkamp, a student at the University of Amsterdam, also addressed the problem of not listening to knowledge, entitled Oost-Indisch weten [[4]].

If scientists want the world to become a better place, they must take their role in society seriously, which means talking more about science and doing less ‘science’. Or, better still, reframing the role of the scientist and seeing this type of work as the core of their profession.

Some readers sometimes ask me how I find the time to put into this newsletter, but I see it as the most important part of my work; it's not something I do on the side, it's what I do. So I don't blame young scientists for participating in the rat race because they fear they won't have a job otherwise. But I do blame senior scientists. They can break free from the hamster wheel without much damage to their careers, and they also have the power to change systems, at least more so than young people. What has disappointed me most about “growing old” in science is that the people with whom I made plans to change the system in my younger years are now suddenly not on board, because, for example, they want to rake in some research money before they really openly resist.

"Writing a column like you did in the spring," a former colleague said to me—referring to a column in Volkskrant in which I argued that I don't want to change science at all—"I would never do that. You'll never get a grant from NWO again". Now, it seems highly unlikely to me that my chances at NWO depend on what I write in the newspaper, but this does indicate what this person's priority is, and it is not improving science.

And then the AI optimist will say: but Felienne, AI will give us more time for knowledge sharing! With AI, you can write a paper in half the time, and then we can broaden science, share our knowledge in the newspaper and on TV, and debate it in the community center!

But that is highly unlikely for a number of reasons. And I don't even mean that it's questionable whether AI really saves time, as recent research by Neil Selwyn, for example, has shown.

Rather, I mean that in a world where AI exists, communication tasks are still not rewarded. Your manager doesn't look at it, and your fellow scientists will unfortunately take you less seriously, not more seriously, due to the Sagan effect. So why would you do science communication when you could just write two papers in the same amount of time?

Scientists that we currently recruit as universities not only do not want to do science communication, they are also unable to do so. Or rather, if they can do it, it is by chance; it is not a skill that is generally looked for when you are hired somewhere.

And, as a final argument, there is the question of who will read all those papers if we can write so many with AI. Optimists say that AI can summarize them all for us and that we will only need to read those summaries. But will that lead to more knowledge? It sounds paradoxical, but I think that this approach will result in less knowledge in the world. Because acquiring knowledge is not just about knowing facts, but also about being prepared to defend the knowledge you acquire. A few weeks ago, I quoted Peter Naur's paper Programming As Theory Building, which says that when you think about something, you also create a theory in your brain. For him, a theory means:

the knowledge a person must have in order not only to do certain things intelligently but also to explain them, to answer queries about them, to argue about them, and so forth.

By actively thinking about something (Naur relates this to programming), you develop a theory, and so you can explain not only what it says, but also why.

Ironically, Naur's paper is a good example of science communication, because he does not write so much about his own work, but mainly translates work from the cognitive science of philosopher Gilbert Ryle to a computer science audience. I was not familiar with this work of his, but I was familiar with all his technical work on creating programming languages.

According to Naur's theory, which I fully subscribe to, the kind of knowledge you gain from reading summaries alone is very different from the knowledge you gain when you are actively engaged with a subject in some way. And only that kind of knowledge can be explained, defended, and discussed, which are precisely the activities required for communicating science.

[[11]]: Unlike all other disciplines, computer scientists publish mainly in conference proceedings (reports). Other scientists publish mainly in journals (magazines).

[[4]]: I am simply not capable of explaining the rich history of the term Oost-Indisch doof, on which this term is a play.

AI does not think

With all the Delta Plan fuss over the past two weeks, there has been no room at all for a very nice story by Rens Bod in Trouw, which he originally wrote in response to my piece in Trouw a few weeks ago, which I was allowed to read aloud at the award ceremony for educational journalism. AI, says Bod, does not think at all, and we need to tell students that (both pieces in Dutch).

Rens Bod is not the only one who says this, by the way. Last week, in The Verge, we could read a very nice summary of an opinion piece from Nature entitled Language is primarily a tool for communication rather than thought. This highly readable piece nicely substantiates that both “language is necessary for thinking” and “thinking is necessary for producing language” are not demonstrably true, and that a model built solely on language cannot be classified as thinking. So, once more for those in the back: an LLM does not think.

Bod is actually very positive because he says that AI may allow us to regain "something of the age-old humanistic tradition":

If we return to that tradition of critical thinking, the AI revolution is a hidden blessing: thanks to generative AI, we will once again appreciate the age-old humanistic pursuit of truth.

I hope he's right! As a writer, I certainly notice this effect; I have become much more precise in citing sources in recent months. I used to trust what I read online, but now I check everything. Now, that's not a blessing, it takes the fun out of reading, but it does ensure that I myself have become much more accurate in my citations, and I admit, that's a gain.

And it seems that a focus on slow and precise reading in the lecture hall can also work, I read in a very uplifting piece in New York Times Magazine. He says we need to talk about what AI tempts us to do:

You can’t address A.I.’s effect on writing without considering its invitation to settle for a summary of content instead of actually reading.

Yes, the lure of reading more quickly, with less attention to detail, and of course much less exposure to rich text and therefore vocabulary. You have to relate to that. So instead of making your courses AI-proof with strict controls, it's better to use an AI-resistant approach, says Carlo Rotella, an English teacher at Boston College:

An AI-resistant English course has three main elements: pen-and-paper and oral testing; teaching the process of writing rather than just assigning papers; and greater emphasis on what happens in the classroom.

These all seem like sensible suggestions to me, more sensible than what VU University Amsterdam proposes in their (I refuse to say ‘our’) AI Literacy Companion, which describes ‘Learning Supportive Use’ as how you can use AI when you get stuck.

You've been given a challenging research assignment, but your head is full of random ideas and you're not sure where to start. Instead of panicking and endlessly scrolling through sources or staring blankly at your screen, you open a generative AI tool such as ChatGPT. You enter a specific prompt with your random ideas: “Imagine you are an environmental lawyer. Give me three perspectives on the legal implications of microplastics in European legislation.” Useful angles, suggestions for sources, and a proposed structure appear. You rewrite, reflect, search further, delete, add new parts, but that first step has been taken. AI works for you, not the other way around.

It's really infuriating that this struggle, from which you can learn so much when you discuss it with students, has to be brushed aside, and that students can never bring their own ideas to the surface because they start with the idea of AI and from there they only have to delete and add. Between the lines, you see an absolute focus on the product, which has to be good, and you have to use AI for that, because handing in a blank sheet of paper is not an option.

Technology completely obscures the student's learning process. I can no longer see whether a student has written a beautiful piece themselves, or whether they have taken it from AI, or something in between. How am I supposed to assess how they are doing?

Under the guise of preparing students for the future, decisions are being made here about how I should teach and what I do or do not want to see from a student. The process of struggle is being hidden from my view, against my will. And that power then lies, as I also said on the Jonge Akademia podcast, with a (most likely American) company.

Professor Michael Clune of Ohio State University referred to these kinds of plans in The Atlantic as the “self-lobotomy” of universities:

such policies represent a dangerously hasty and uninformed response to the technology. Based on the available evidence, the skills that future graduates will most need in the AI era—creative thinking, the capacity to learn new things, flexible modes of analysis—are precisely those that are likely to be eroded by inserting AI into the educational process.

Exactly, there is no evidence whatsoever that this use of AI benefits the learning process, and in my classes I do the opposite, focusing on the process itself. I did this with labor-based grading, where my students were allowed to submit three drafts during the semester, and if they did so, they were guaranteed a passing grade. I didn't care what they submitted, I didn't judge, but I did give feedback. Spelling mistakes, messy thoughts, random ideas that popped into your head, really anything was fine with me, and it was wonderful! Students found it liberating, and to be honest, so did I. In many cases, the students said that knowing I wouldn't judge them helped them get something down on paper.

It's better to pay attention to them while they're still working than after the semester when all they care about is their grade, Rotella quotes his colleague Maia McAleavey.

And that works, Rotella agrees.

It has come as a pleasant surprise to me and to many of my fellow teachers that the A.I. apocalypse that was expected to arrive in full force in higher education this fall, bringing an end to reading and writing and school as we know them, has not come to pass just yet. Responding to the rise of A.I. by doubling down on the humanity of the humanities appears to be working, at least for the moment.

The entire piece is full of truly delightful AI-resistant lesson suggestions, such as five-minute quizzes with questions about very obscure details, such as what Anna's son received as a birthday present in Anna Karenina in 1875, or asking students to hand in their handwritten notes so that he can “see them think.”

But Rotella also sees the bigger picture, in his call to emphasize how special it actually is to get together with a group of people and read a piece really deeply and discuss it with each other. You'll probably never do anything like this again in your life, so enjoy it while you can.

This tech-obsessed moment may have finally pushed humanists to identify the value of their disciplines and play to their strengths, after first going fetal for far too long when assailed by return-on-investment literalists who willfully misunderstand the fit between school and work (“There is no job called English or history”).

Yes, perhaps this AI hype is a blessing in disguise and we realize that universities have allowed themselves to be held hostage by the labor market perspective for far too long. A person can dream, right?

The end of subtitling?

In week 36, I talked about the undividedly positive effect of subtitling on the English language skills of Dutch people, and wrote, “It's a shame that AI is going to make all those subtitles unreadable”, not knowing how quickly it would happen. Because, as I read in a LinkedIn post by Piek Knijff, there are apparently already English-language series that are being dubbed into Dutch using AI.

Yuck! Not only is Piek's argument valid, that children become so accustomed to fake language from fake people, but we are also missing out on a whole standard deviation of improvement in English for free; a rare example of how learning can happen with very little explicit effort. Now, true AI fans will of course say that soon we won't need to know English at all, because we'll be wearing a babelfish... but that's beside the point.

What's happening on TV now will undoubtedly soon be on YouTube and TikTok, the places where young people also learn English, because all tech companies are looking for places to use AI.

The predictable result is that Dutch young people will soon speak English less well, and who is responsible for that? Whereas in the old world, broadcasters acted as gatekeepers, determining what we got to see and how (which of course caused all kinds of problems!), now a product owner at a large software company in America–someone who in all likelihood is not even bilingual or familiar with research demonstrating the benefits of subtitling—determines what and how Dutch citizens watch tv.

The ubiquity of AI has countless problems, but one of the more subtle ones is the slow shift of decisions that used to be made by people close to the action—a broadcaster about the language of programs, a doctor about how he dealt with patients, a teacher who constantly made choices about students—away from these experts. The decisions that really matter are now being made by companies.

Question from a reader: how is your newsletter different from a paper or a tweet?

I'll also take a reader question. I know, I have a dozen more in the queue, sorry if I haven't gotten to yours yet *something something deltaplan*. I really liked this one, someone asked me how writing my newsletter compares to my previous work, both my heyday on Twitter and writing papers.

I really started my newsletter because I missed Twitter so much [[12]]. For 10 years, I read the news and thought about everything: I have an opinion on this too, and hop online, and I noticed that my thoughts just kept tumbling over each other without an outlet. So in that respect, a newsletter does fill the role of tweets for me.

So far, I really like two things about my newsletter, compared to other places.

First, it's great to be able to revisit topics. On Twitter, you rarely referred back to a tweet from weeks ago; it just didn't fit with what it was for. As McLuhan writes in the delightful Amusing ourselves to death:

...consider the primitive technology of smoke signals. While I do not know exactly what content was once carried in the smoke signals of American Indians [sic], I can safely guess that it did not include philosophical argument. Puffs of smoke are insufficiently complex to express ideas on the nature of existence…. You cannot use smoke to do philosophy. Its form excludes its content.

Returning to pieces—"as I wrote earlier" is probably the most commonly used text here—allows me to think more deeply about topics and remember better what I myself have written [[13]] .

What I also love is that I can write the way I read. In recent years, I have greatly enjoyed good non-fiction and scientific work in ethnography, philosophy, and feminist theory. David Graeber, Mary Midgley, Mary Beard, all wonderful! These often use beautiful storylines underpinned by terms, ideas, and stories from other books. I didn't read that kind of text during my PhD, only papers describing experiments and their results, and you can't want to become something you don't know.

But now that I'm reading these kinds of texts, I feel that my brain works the same way; I work out my thoughts and while I'm doing that, I think: so-and-so wrote about that too, let me find my notes and make a good connection. It feels like coming home after a long trip.

[[12]]: I will probably never have 16,000 followers anywhere again 😭! If you want to ease my pain, please forward this newsletter to someone, so that I might one day reach 5,000 subscribers. That seems like a very nice goal to me!

[[13]]: I'm helped in this by the fact that my newsletter platform is linked to Obsidian, which makes it very easy for me to search through everything and quickly link to older posts.

Good news

The exhibition Alice and Eve, which puts 30 female computer scientists in the spotlight to show that we women also contribute to computer science, has won an award (and I'm one of those 30, isn't that cool?!)

And then some more good news, but not for you and me. Members of Congress in the US who go on to hold leadership roles earn 47 percentage points more than other politicians. According to the study, this is partly because they trade in stocks that later receive large contracts!

Thanks to hero Bert Hubert, the AIVD has stopped using Google Analytics on job vacancies, and that news even reached the international media! Quite rightly so, because in this geopolitical climate, it may not be so convenient for the US to know who our future spies will be.

Bad news

Zomergasten is ending. Well, there goes my biggest dream of ever becoming a summer guest. Joris Luyendijk rightly called it NRC's bullying cutbacks. With the quote (from Telegraaf columnist Rob Hoogland): "I'm not right-wing, I just hate the left." I think we can see exactly how true that is in the elections and the VVD's continued refusal.

The Dutch government is making increasing use of generative AI, according to research by TNO and reported in NRC. This raises questions "about control, security, and digital independence" because these models often use American software. Wiep Hamstra, a friend of the newsletter, also expressed criticism of TNO's findings in Volkskrant (both in Dutch):

While we first test medicines extensively under controlled conditions, experiments with AI take place in the midst of society.

Carnegie Mellon predicts that electricity rates in America will rise by 8% in 2030 due to more data centers on the power grid and crypto mining.

And then, according to a leak, chatGPT will soon start showing ads, and some users have already seen them, even though openAI quickly denied this. Be that as it may, openAI needs a revenue model, the party is over, Laurens Verhagen wrote last weekend in Volkskrant, so if it's not ads, it will be something else.

Enjoy your sandwich!

Member discussion