AI in week 50

Goed nieuws: de kerndoelen Digitale Geletterdheid zijn goedgekeurd, dus kinderen in Nederland gaan binnen afzienbare tijd allemaal leren over AI, programmeren en de digitale wereld. En ik moest weer denken over denken, en over de rol van links in het AI debat.

I did not have time for an English translation this week! Now added!

Maken is mooi

Als er een uitspraak voor mij aan 2025 verbonden is, dan is het wel deze:

The secret of quality is love

Ook al is de uitspraak zelf uit 2016. En ik zag deze week weer een absoluut amazing stuk in New York Times waarvoor dit dubbel waar is!

Het stuk zelf is waanzinnig mooi vormgegeven, je begint met lezen en dan scrol je langs filmpjes die alles zo mooi afmaken. Maar ook het onderwerp is één grote ode aan vakmanschap en liefde, voor een onverwacht object, namelijk de typemachine.

Dit is hoe je de digitale wereld kan gebruiken om verhalen te vertellen, dít is meer dan papier, meer dan video, maar zijn hele eigen ding. Hoe jammer dat stukken in de digitale wereld vaak gewoon een computerversie zijn van een statisch stuk.

Maar wat mooi dat leerlingen in de (niet al te verre) toekomst, ook gaan leren hoe ze digitaal kunnen maken, want... tromroffel!!!!!

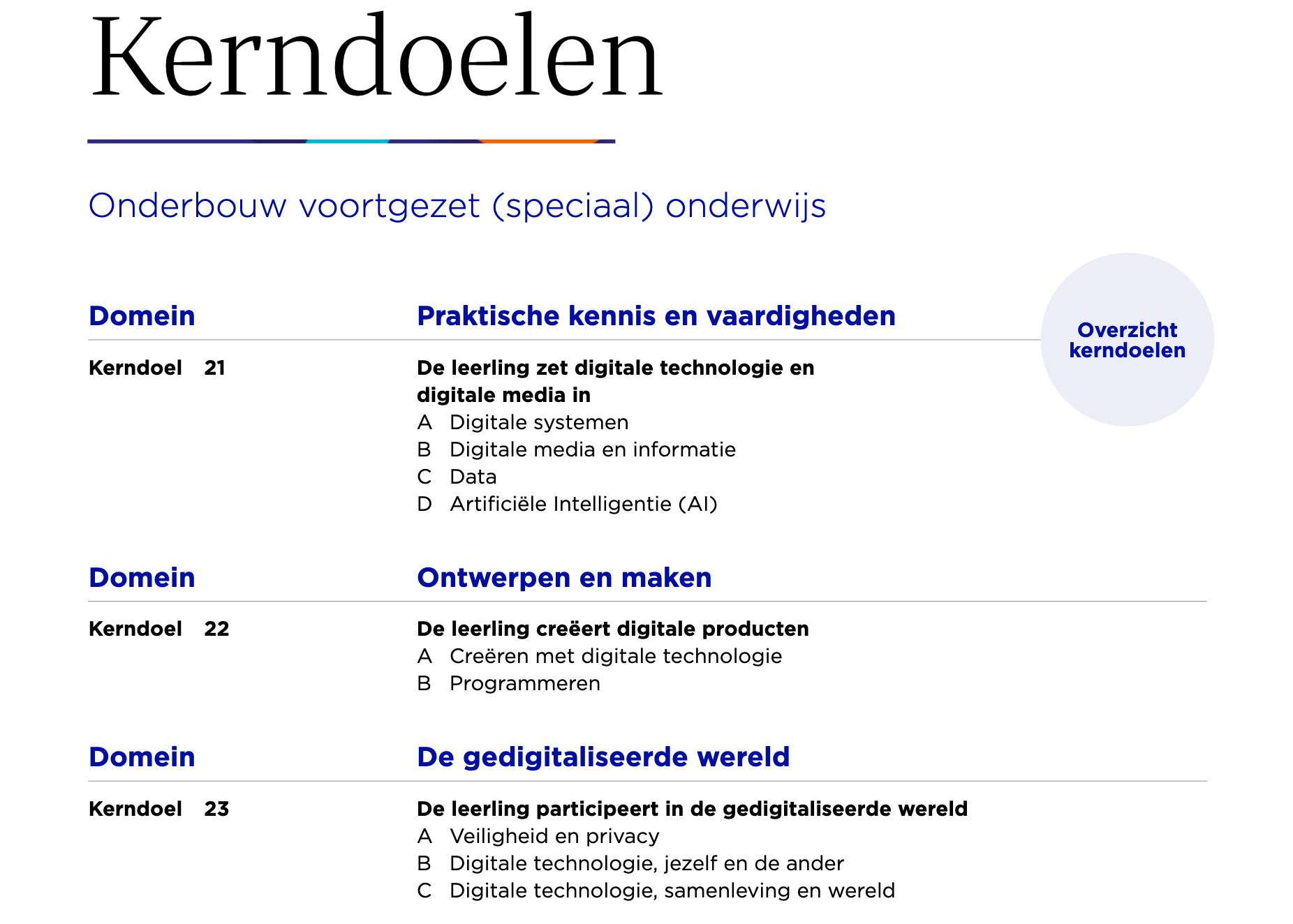

De nieuwe kerndoelen voor digitale geletterdheid zijn door de Tweede Kamer goedgekeurd, doelen waar ik in 2022-2023 ook aan heb mee mogen schrijven. Alle leerlingen in de onderbouw van de middelbare school moeten straks aan deze dingen gaan werken (en ook op de basisschool gaan ze vergelijkbare dingen doen).

Ik zal vast in een andere editie nog eens terugkomen om doelen 21 en 23 waar AI een grote rol speelt, maar nu kies ik voor doel 22, omdat het zo mooi past bij dat typemachinestuk. Want niet iedereen was enthousiast over de kerndoelen, er kwam zelfs een site tegen de doelen, vol met, hilarisch genoeg, AI-afbeeldingen. "Leerlingen moeten ‘digitale producten’ maken." luidde de kritiek "Maar er staat nooit waarom."

Nou is dat natuurlijk eenvoudig te weerleggen onzin, want we schrijven weldegelijk over het waarom:

Leerlingen leren om kritisch te kijken naar digitale technologie en digitale media, deze te doorgronden en op basis daarvan hun handelen aan te passen. Ook leren ze dat het mogelijk is om invloed uit te oefenen op de ontwikkeling van digitale technologie en digitale media.

Maar als dit niet duidelijk genoeg is, laat de schitterende typemachines je dan overtuigen. Ik wil dat leerlingen hun gedachten en verhalen en plannen in zulke mooie digitale vormen kunnen gieten, naast in posters, spreekbeurten en toneelstukken.

Zoals ik las in deze schitterende (wat late) obit van schrijfster Abigail McGrath in Harper's Bazaar, kunst is een weg naar een andere wereld.

Misschien wordt dit mijn slogan van 2026!

Ow en over 2026 gesproken... Het Stimuleringsfonds voor de Journalistiek vroeg twaalf journalisten en andere experts wat hun voorspellingen en wensen zijn, en ik sta er ook tussen met een supermooie illustratie van Chuan Ming Ong.

Lezersvraag zonder antwoord!

Ik kreeg een leuke vraag van lezer Niels, IT-er bij een Amsterdamse onderwijsorganisatie, waar ik het antwoord ook niet op weet, dus ik deel 'm hier (iets ingekort). Het is trouwens niet alleen een vraag, maar ook een soort sign of the times.

Ik zoek naar aanleiding van de AI Act een nuchtere basis AI-geletterdheidstraining voor mijn collega's. De eerste resultaten bij google bij het zoeken naar "AI geletterdheid training" zijn die van De Nationale AI-cursus Basisdiploma AI Geletterdheid, dat lijkt een mooie website met goede filmpjes. Maar bij de lijst met sponsors kreeg ik al argwaan, en bij het volgen van de basiscursus ben ik geschrokken hoe commercieel dit is. Zo komen o.a. deze drie deskundigen vooral aan het woord, maar zijn niet bepaald onafhankelijk:

Rob Elsinga, National Technology Officer (NTO) bij Microsoft Nederland

Claire Zitman - Director of AI Projects at KickstartAI

Onno Zoeter - Head of Booking AI Research bij Booking.com

Erg jammer, want ik had hoge verwachtingen. Bij de naam ‘De Nationale AI-cursus’ zou je denken dat het een neutrale overheidstraining is. Vooral omdat het ook door de overheid zelf wordt genoemd op Wat je moet weten over AI-geletterdheid - Digitale Overheid

Ik heb ook de training AI en Ethiek bekeken op dezelfde site. Deze is een flink stuk sterker (veel meer beschouwend), maar vooral verdiepend en weinig praktisch. Gaat ook over sociale media, monopolies en de rechtsstaat, voor nu zoek ik een basis AI-geletterdheid training.

Een andere hoge hit op google is https://ai-geletterdheidcursus.nl/, maar dit blijkt van Copilot Academy te zijn, die weer diep in de Microsoft trainingen zitten Microsoft Copilot Training in Nederland | Copilot Academy. Als hun naam dit niet overduidelijk weggaf, zou je geen idee hebben.

Heb jij een goede tip voor Niels, dat hoor ik dat graag, ook voor andere lezers is dat heel relevant natuurlijk. Maar zoals gezegd, het zegt ook veel over de wereld waar we nu in leven. Het vrije internet vol persoonlijke weblogs, gratis goede kennis van publieke partijen zoals de bieb of omroepen, dat is er niet meer.

Het lijkt er dus ook wel op dat er een markt zou zijn (o, de ironie van deze formulering, I know) voor een goede neutralere AI-cursus zonder winstoogmerk.

Een links/progressieve blik op AI

Waar blijft de tijd dat universiteiten en studenten progressief waren en bedrijven en politiek conservatief?

Zo schrijft Jeroen van Glabbeek, CEO van telecombedrijf CM op Linkedin. Of ja telecombedrijf, als je op hun site kijkt zie je dat de voormalige smsjes-verkoper nu helemaal ingezet heeft op AI:

CM.com’s AI-powered engagement platform helps you engage customers through AI Agents, unified data, and real-time communication across marketing, service, and sales.

Als ik dit soort teksten lees dan denk ik echt: wat staat hier? Waar is Japke-D, die vrouw moet toch wel de time of her life hebben in deze bubbel. Ik kan het 10 keer lezen en dan weet ik nog niet wat dit voor bedrijf is en dan weet ik nog van de meeste woorden in deze zin wat ze ongeveer betekenen.

Anyway, van Glabbeek is niet de enige die zich verwondert over het gebrek van enthousiasme voor AI bij links, ook op de linkse blog Jacobin, die nota bene naar eigen zeggen "de ideeën uit de intellectuele traditie van het analytisch marxisme voor het grote publiek toegankelijk maken", krijgt links een veeg uit te pan. Want, zo schrijft, Savriël Dillingh, promovendus in de economie aan Erasmus, AI is niet het probleem, kapitalisme in het probleem.

Nu ben ik het daar natuurlijk roerend mee eens, maar toch mist Dillingh een paar relevante punten. Maar voor ik daar verder op inga, moeten we misschien eens definiëren wat links is, of althans wat dat voor mij betekent. Want links verenigt verschillende soorten mensen en opvattingen, die elkaar soms tegenspreken. Maar net als bij lekker eten, of mooie muziek, ja, smaak speelt een rol, maar er is ook zoiets als een gedeelte realiteit waarin de meeste mensen verse appeltaart lekkerder vinden dan slappe friet, en Joni Mitchell beter dan Eurodance.

Voor mij betekent links streven naar een eerlijkere wereld met meer gelijkheid. Traditioneel heeft links allereerst een arbeiderstak, die streven naar gelijkheid tussen arbeider en eigenaar van de fabriek, waarom zou de eerste minder verdienen en minder te zeggen hebben dan die tweede? Dat gelijkheidsideaal breidde zich daarna uit naar de vrouwenzaak: waarom mogen vrouwen niet stemmen en studeren? Waarom werken mannen buitenshuis met ontvangst van bijbehorende status, financiële zekerheid en lol die daarbij hoort, en vrouwen niet? Waarom is de zorg voor kinderen en ouderen niet eerlijker verdeeld.

De progressie die links dus aanhangt (of volgens mij zou moeten aanhangen) is geen technologische progressie, geen vooruitgang om de vooruitgang, maar een progressie weg van de ongelijkheid die zich sinds jaar en dag in onze samenleving heeft ontwikkeld. Even zo zit wat conservatieven willen conserveren vaak in de hoek van traditionele rolpatronen en regelgeving.

En hier zit ook meteen het probleem van hedendaags links: we hebben gewonnen. Ik weet dat het nu echt niet zo voelt en ik zit ook regelmatig stomend aan de eettafel mijn man te vertellen wat er nu weer mis en oneerlijk en lelijk is in deze tijdslijn, maar ik zal eens ongekend positief zijn en dit benoemen. Vrouwen mogen stemmen, studeren, kunnen hoogleraar worden (met 30% zijn we, mat LNVH deze week). En ook de zoon van de bakker mag studeren, kan studeren en doet dat ook. De enorme toename van studenten in het hoger onderwijs–in 1990 studeerden er in Nederland 180.000 mensen, in 2000 230.0000 en 2014 waren het er al 255.000 —is natuurlijk niet toe te schrijven aan dat we allemaal slimmer zijn geworden, dat is het effect van het toegankelijk en eerlijker maken van school, want die stijging zit 'm vooral in toename van het aantal vrouwelijke studenten in het hoger onderwijs. Het percentage vrouwen ging van 42% in 1990 naar 51% in 2014.

Dus we kunnen stellen dat het ons is gelukt, en juist daarmee is het samenbindende verhaal van de ongelijkheid weggevallen. Want het verhaal van oud-links was: Kijk dat onrecht daar eens! Die regel dat vrouwen geen bankrekening mogen hebben, die moet weg. Als we willen dat iedereen kan studeren moet dat wel betaalbaar zijn, dus we moeten studiefinanciering invoeren.

De toplaag van problemen, die zijn opgelost, en dingen waar we nu naar moeten wijzen zijn zo onzichtbaar dat ze onbenoembaar worden. Zoals Christien Brinkgreve schrijft in Beladen Huis (waaat een boek trouwens, dank aan mijn moeder voor de leestip, daar ga ik zeker later nog meer over schrijven):

Jaren feministische strijd weten deze dieptelaag vrijwel intact te laten. [...] Het is een andere laag dan die van de wetten en de regels, ongrijpbaarder, taaier.

We moeten dus in deze wereld meer moeite doen om de oneerlijkheid te benoemen, en we moeten dat doen in een wereld waarin onze spirit, zoals A.R. Moxon het noemt, gevangen is door het idee dat de wereld eerlijk is, en dat mensen dus krijgen wat ze verdienen. Het verhaal van de American Dream is ook in Nederland het narratief waarin we hangen: Met hard werk kom je er wel, de echte barrières zijn immers verwijderd. Verhalen over die ene vrouw, Marokkaan, Surinamer, rolstoelgebruiker etc. die het wel gelukt is, die worden verteld en gevierd.

Een CEO die 200x zoveel verdient als mensen in de fabriek? Ja, dan hadden ze maar harder moeten werken. Een vrouw die het niet redt in de wetenschap omdat ze ook kinderen opvoedt? Ja, die is niet slim en gedreven genoeg. Niets stond haar in de weg, toch? Er zijn nu toch meer vrouwen dan mannelijke studenten?

In de wereld waarin het nieuwe links geen duidelijk verhaal meer heeft, blijkt het voor links dan ook heel lastig om zich goed te verhouden tot de wereld, en dus tot AI. Is het nu een middel voor gelijkheid tussen mensen of juist niet? En als het dat niet is, waar zijn we dan tegen? Tegen algoritmes? Tegen big tech? Tegen extractie?

Er komt geen helder tegengeluid, en dan moet je je gaan afvragen: Haten linkse mensen zoals Savriël Dillingh schrijft, het kapitalisme eigenlijk wel? Als ik het enthousiasme zie waarmee links rechtse idealen als productiviteit en groei omarmt, dan is er volgens mij voldoende reden om daaraan te twijfelen.

Kan AI denken? The sequel

Er is bewijs voor AI Consciousness, en niet volgende week, nee nu al, aldus deze ronkende headline van Cameron Berg in AI Frontiers, waar "expert dialogue and debate on the impacts of artificial intelligence" plaatsvindt.

Of ja, als we even de ondertitel lezen ligt het meteen al genuanceerder: "A growing body of evidence means it’s no longer tenable to dismiss the possibility that frontier AIs are conscious."

Ah ja, we weten het nog niet maar er komt steeds meer bewijs dat we het zomaar verwerpen van AI-bewustzijn niet echt meer kunnen verdedigen. Het zijn eindeloze semantische spelletjes, en dat begint al met het ontbreken van een definitie maar daarover toch nog heel wat kunnen zeggen:

Defining consciousness. “Consciousness” is a notoriously slippery concept, so it’s important to be explicit about what I mean. I am referring to the capacity for subjective, qualitative experience. When a system processes information, is there something it is like, internally, to be that system beyond the merely mechanical? Does it have its own internal point of view? In short: are the lights on? (originele nadruk).

Nee maar even serieus, wat staat hier? "beyond the merely mechanical" Ehm een computer noch een mensenbrein is mechanisch... En is het licht aan? Heb ik soms een ledje in mijn kop? Het is zo verleidelijk om zo'n stuk (on)zinnetje voor (on)zinnetje te weerleggen, maar dat is nu juist precies wat zo'n auteur wil: de discussie voeren, het debat aanjagen.

En ik heb lang gedacht dat ik verbaal het masker er wel af kon trekken, kom op mensen bij Anthropic, hebben jullie het nou serieus over de ziel van Claude? Hedde drugs op?

Maar ik trap er niet meer in, want het is zinloos. Zie je het zelf al, dan heb je mij niet nodig, en vind je dit indrukwekkend klinken? Dan is er niks dat ik kan zeggen dat je van gedachten laat veranderen, en bovendien dan trok je deze nieuwsbrief toch niet.

Ik merk dat ik het veel interessanter vind om te ontrafelen wat de denkkaders zijn van mensen uit deze hoek, want als je die snapt, dan kan je op een veel dieper niveau zien wat de onzin is, en hoef je je niet steeds met losse gedachtes bezig te houden. Twee dingen vallen in het denkkader steeds op:

Een diepgeworteld ongemak met geloof

Ok, dit klinkt out there, I know maar geef me even. De vraag of een computer kan denken is op het diepste niveau een vraag over geloof. Geloof je dat een mens meer is dat een verzameling cellen die rekenen? Het stuk van Anthropic benoemt dat zelf:

We believe Claude may have functional emotions in some sense (nadruk van mij)

Het oneens zijn over geloof is van alle tijden, en is prima.

Ik geloof niet dat Claude emoties heeft, persoonlijk, want ik denk dat mensen een "iets" hebben; een unieke combinatie is van je genen, je omgeving, al je ervaringen en kennis, dat maakt je tot wie je bent. Je hoeft niet eens te geloven dat dat iets een ziel is die door een god gegeven is, om te geloven dat ieder mens uniek is. Je hoeft maar een klein kind te zien opgroeien die langzaam een eigen karakter ontwikkelt, om te zien: hier zit een uniek mensje in wording, anders dan alle andere mensen.

Maar "big tech" mensen [[1]] geloven dat over het algemeen niet, die geloven, zoals Michiel Bakker en Cameron Berg, dat mensen computers zijn. Nu is daar alleen in praktische zin al voor op aan te merken. Zo toont nieuw onderzoek aan dat je darmen een sterke invloed hebben op je mentale gesteldheid. Zelfs als je gelooft dat Claude emoties heeft, dan zijn dat dus hele andersoortige emoties dan mensen met ingewanden hebt. Maar vooruit, als we denken aan een technologie in de heel verre toekomst waarin we ook de darmflora van de robotten gaan simuleren dan hebben ze misschien vergelijkbare emoties.

Maar in die wereld of in deze, we weten niet of een machine een ziel heeft, of kan hebben in de toekomst. Het enige dat we kunnen doen is verschillen in ons geloof, ik geloof dat in de ziel en jij niet. No biggie, op zich.

Maar nu komt het probleem, de subcultuur die dit soort dingen denkt, is opgegroeid met een diep wantrouwen voor geloof. Geloof is geen acceptabele manier om een debat te voeren of te beëindigen. De huidige Silicon Valley subcultuur heeft stevige wortels in New Atheism, de beweging uit de vroege jaren 2000 die rationaliteit boven geloof stelde.

Maar de anti-geloofsvibe gaat natuurlijk nog veel verder terug, al eerder schreef ik over de hiërachie van wetenschappen waarin wiskunde met pure bewijzen en redeneren ver boven andere manier van denken staat. Een informatica-studie zorgt ervoor, zoals Joseph Weizenbam zei, dat je alleen nog op de wetenschappelijke manier kan denken:

I am constantly confronted by students, some of whom have already rejected all ways but the scientific to come to know the world, and who seek only a deeper, more dogmatic indoctrination in that faith (although that word is no longer in their vocabulary).

Het idee dus dat ze moeten toegeven dat iets dat ze denken uiteindelijk rust op iets wel of niet geloven, dat veroorzaakt kortsluiting. De enige manier van overtuigen, zowel een ander als zichzelf, is het opzetten van argumenten en het presenteren van bewijs. Niet voor niets komt het woord 'evidence' 20 keer in het stuk van Cameron Berg voor, en word je om de oren geslagen met studies over zelf-bewustzijn, pijnvermijding en aandacht: gedrag dat mensen uiteindelijk toeschrijven aan output van computers.

Ik moet dan altijd denken aan de Heider-Simmel Illusion (ik schreef er al eerder over). Maar ken je 'm niet bekijk deze video dan eens.

Ongelofelijk toch dat je meteen emoties en motieven toeschrijft aan die figuurtjes? Ze zijn boos en bang, ze vluchten, ze slopen, ze verstoppen. En dat terwijl je weet dat je naar geknipte vouwblaadjes zit te kijken! Geen wonder dus dat we bij iets wat heel wat ingewikkelder klinkt ook gaan denken aan emoties.

En dan toch nog even over het bewijs dat volgens het stuk in veelvoud "point[s] toward consciousness-like processes in AI systems"

Dat bewijs, zo blijkt uit onderzoek van oa The Oxford Internet Institute, is vaak helemaal niet zo stevig. Veel benchmarks, datasets om te testen wat AI kan, "fail to define what exactly they aim to test"—herkenbaar als je ziet hoe slecht doelen van AI overal meestal gekaderd zijn. En niet hier of daar een foutje, nee:

However, roughly half of the benchmarks examined in the study fail to clearly define the concepts they purport to measure, casting doubt on benchmarks’ ability to yield useful information about the AI models being tested.

En zo nieuw is dat idee trouwens niet, Emily M. Bender noemde zulke benchmarks in 2021 (dus vóór de huidige chatGPT hype) met de voor haar karakteristieke humor al "Everything in the Whole Wide World Benchmarks" en dan niet op haar blog, maar op NEURIPS, dé AI conferentie.

Identificatie met machines

Het andere deel van het wereldbeeld is een diepgewortelde affiniteit met machines, zo diep dat die gaat boven affiniteit met andere mensen, zeker mensen die niet op ze lijken. Laat deze zin bijvoorbeeld maar even goed op je inwerken.

Failing to recognize genuine AI consciousness means permitting suffering at an industrial scale.

Als we geen rekening houden met het idee dat AI een bewustzijn heeft, dan staan we leed toe, op een industriële schaal zelfs.

Zelfs als je gelooft dat dat waar is, en dat je dus dat een AI zich net als mensen kan vervelen, boos of verliefd kan worden, dan nog moet je dat leed zien in verhouding tot mensen die nu al bestaan in de echte wereld.

Mensen die voor een grijpstuiver onthoofdingen of kinderporno moeten bekijken zodat AI het niet aan jou toont.

Mensen die kanker krijgen omdat ze bij een datacentrum in de buurt wonen. Mensen, kinderen nog, die kobalt en koper uit de grond halen.

Het vergt een heel speciaal soort mens om wel te denken aan het mogelijke lijden van de AI computers en niet aan het ontegenzeglijke lijden dat AI nu al veroorzaakt in mensen.

[[1]]: Niet iedereen die bij een groot techbedrijf werkt, denkt natuurlijk zo. Maar het gaat over de algemene denkwijze: wat kan je in Silicon Valley en omstreken zeggen zonder dat ze je raak aankijken?

De mythe van twee-sigma

Heel veel onderwijsvernieuwing leunt op het idee dat leerlingen, uit vrije wil en helemaal zelfstandig, met een technologie gaan leren, ook bijvoorbeeld de fantasie van Werner Vogels van Amazon, die net als ieder jaar een voorspelling voor het komende jaar schreef.

Dat idee is in de basis erg eenvoudig te ontkrachten, zelfs wij volwassen leerders gebruiken alle nu al op het internet aanwezige kennis maar nauwelijks om echt te leren, liever kijken we naar kattenfilmpjes of influencers. Het allerbeste dat het internet qua leren heeft voortgebracht is DuoLingo, dat je met punten en streaks probeert te verleiden tot leren, en als dat niet lukt het register chantage aanboort en het vrolijke logo laat verworden tot een uilen-lijkje met virtuele vliegjes eromheen.

Het werkt gewoon niet, wie kent er nu niet iemand met een giga-streak en weinig echte kennis?

Iedereen weet: je echt iets wil leren, dan neem je les. Alleen al de "dwang" van ergens naartoe moeten, zorgt ervoor dat je het ook gaat doen, en je investering in geld maakt dat je je ook aan je voornemen houdt.

En fair enough ook! Je moet al zoveel in het leven, lekker op de bank Netflixen is toch veel fijner dan 's avonds nog moeten leren? Leren is taai, je moet stampen, en je wordt voortdurend geconfronteerd met je eigen onkunde—ik toonde mijn leerlingen van de week trots mijn kennis van het Arabisch en ik haalde na anderhalf jaar les de ta en de ya weer door elkaar. Als wij, volwassenen met tijd en goed ontwikkelde metacognitieve vaardigheden niet en masse het internet (of boeken, voor mijn part) gebruiken om slimmer te worden, hoe kunnen we dan in godsnaam verwachten dat tieners dat doen?

Onderzoek na onderzoek na onderzoek toont dan ook aan dat tieners dat niet doen. Projecten waarbij laptops werden uitgedeeld zodat kinderen konden leren programmeren mislukten faliekant, kinderen gebruikten ze om, quelle surprise, videos te kijken en muziek te luisteren. Ik schreef al eerder over het boek Charisma Machine, die dat zo fantastisch beschreef, en heb je geen zin in een heel boek? Hier is een recent paper dat ongeveer hetzelfde beschrijft. Geen zin in een heel paper? Als je alleen de abstract hebt, heb je het ook wel.

Following schools over time, we find no significant effects on academic performance but some evidence of negative effects on grade progression. Following students over time, we find no significant effects on primary and secondary completion, academic performance in secondary school, or university enrollment.

Deze studie was serieus, en volgde 531 kinderen, tot tien jaar na de pilot!

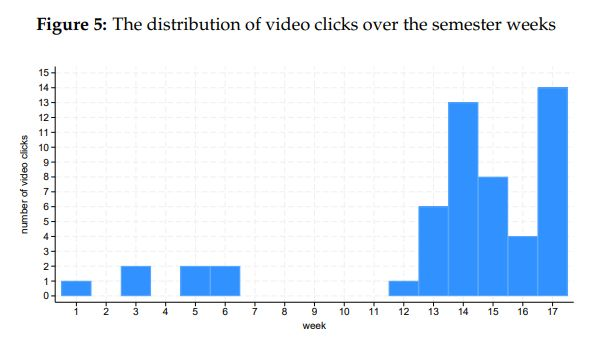

De voorbeelden zijn eindeloos, vorige maand verscheen er weer een paper dat aantoonde dat studenten video's laten kijken in plaats van echte colleges (LeKKer EFfiCieNt!) niet helpt. In München hebben wetenschappers twee versies van hetzelfde vak bekeken, eentje met echte colleges en eentje met videos. Verder leken de vakken zo precies mogelijk op elkaar. En helaas, studenten die de videos keken deden het 11% slechter (0.44 standaarddeviatie verschil), en dat verschil was nog groter voor studenten die het op de eerste toets slecht deden. En waar lag dat vooral aan? Nou, dat maar 25% van de studenten de videos uberhaupt bekeek! En de studenten die dat deden deden dat niet gedurende het semester verdeeld, maar, je verwacht het niet, de laatste weken voor de toets.

Dus in plaats van wekelijks wat leren, met herhaling, terugblik, en het toetsen van kennis, bingen ze alles in de laatste weken en dat werkt natuurlijk niet.

Toch duikt deze voorspelling iedere onderwijsvernieuwing weer op, want ja, wat als het lukt? Als het met laptops niet werkte, en niet met MOOCs en flipping the classroom, nu doen we het nog eens over met AI, en niet dunnetjes, maar dik en vet.

Hoe komt het toch dat deze mythe zo hardnekkig is?

Eén oorzaak daarvoor is te vinden in een overbekend paper van de overbekende wetenschapper Bloom (van de taxonomie) over het twee-sigma probleem. Als een leerling één-op-éen tutoring krijgt, presteert die tot twee standaarddeviaties (dat is de twee sigma) beter dan een leerling in een klas. Dat is de droom, als we dat nu toch eens aan ieder kind konden bieden! Hier komt het wereldbeeld van de computernerd weer eens om de hoek kijken. Want wat je hieruit zou kunnen concluderen is dat de mens tot mens relatie is wat die prestatie drijft. Dat een tutor, die jou kent, weet waar je staat, materiaal speciaal voor jou maakt en je aanzet tot leren, dat dat de secret sauce is. Dat correspondeert ook goed met bovenstaand resultaat over de video's want blijkbaar is naar college gaan waar eens mens voor jou speciaal voor de klas is komen staan, die misschien wel zegt "he, tof dat je er weer bent Saskia", iets anders dan een video aanklikken. Maar dat is over het algemeen niet de conclusie van techbros. Die lezen dit onderzoek en denken dan dat wat speciaal is aan die situatie is, de (gepersonaliseerde) kennis die overdragen wordt. Dat stuk denken ze na te kunnen maken zonder de mens erachter. En tsja, dat helpt niet.

Maar als je denkt dat deze ontmenselijking het grootste probleem is, heb je het mis, er is nog een ander denkbeeld dat hier speelt. De andere reden is dat de tech industrie simpel gezegd, volgens Ben Williamson op Linkedin "does not actually even like education". Ik wil nog wel wat verder gaan, ze hebben een teringhekel aan school. Ik las van de week de nieuwsbrief van een jeugdvriend, een man die filosofie en rechten gestudeerd heeft, die nu zonder pardon schrijft dat hij na een of twee jaar had moeten stoppen met studeren omdat hij toen al kon zien dat hij er toch niks aan had.

Het is consumentisme ten voeten uit, alsof je als student in je eerste jaar eventjes in de meloentjes van de kennis kan komen knijpen om te voelen of ze wel sappig genoeg voor je zijn. De vakken waaraan ik het allermeeste heb gehad vond ik in mijn studententijd de stomste en zinlooste. Ik dacht dat ik programmeur zou worden, dus statistiek voelde zinloos voor mij, zeker omdat het boek waaruit we op de TU les kregen voor alle opleidingen hetzelfde was en dus volstond met voorbeelden over fabrieken waaruit te kleine schroefjes stroomden. Jaren later had ik als wetenschapper had ik maar wat veel plezier van wat statistische basiskennis...! Wetenschapsfilosofie vond ik dan wel weer leuk—ik herinner me nog mijn totale verbijstering toen de docent uitlegde dat het verschil tussen 1 en 2 meter iets heel anders is dan tussen 1 en 2 graden—maar nuttig leek me dit soort quizweetjes totaal niet. Dit kwam natuurlijk ook gedeeltelijk door de eerder beschreven "Tema is kut"-dynamiek. Pas nu, vijfentwintig jaar later schat ik wetenschapsfilosofie van op waarde, en vraag het me over 10 jaar nog eens en misschien denk ik er dan weer anders over. Nu zeggen dat je had moeten stoppen is dus ook toegeven dat je nooit meer van mening gaat veranderen over hoe je naar kennis kijkt, wat een droefheid. Ik zal gelukkig zijn als ik over 10 jaar weer anders kijk naar de kennis die ik heb, en de allermooiste mailtjes die ik van studenten krijg zijn als ze zeggen dat ze het nu van mijn vak niet inzagen toen ze het volgden en dat pas veel later gingen doen. Dat je een student dus iets kan bijbrengen wat ze helemaal niet willen leren, dat is vakmanschap, dat kan een app per definitie niet, want die moet je als student vrijwillig opstarten en dat doe je niet als het niet hoeft. En dat je het ze dan ook zo leert dat het lang genoeg blijft rijpen dat ze het later aan nieuwe kennis koppelen. Eat that Duo-uiltje, jij krijgt vast nooit 10 jaar later een bedankmail.

Faux-to-correct

AI, het zit blijkbaar ook in de kaart die Strava gebruikt (was te lui om op te zoeken wat ze gebruiken). Voor mensen die hier niet in de buurt wonen, Aalsmeer ligt ongeveer waar in deze nieuwsbrief Slecht Nieuws staat.

Goed nieuws

Mijn man had er al twee afleveringen opzitten en toen móést ik van hem meekijken, hij was zelfs bereid om de eerste twee episodes nog eens te doen, en nou, he was not wrong! Waaaaat een show Pluribus! Als je het mij vraagt een onverdunde dig op alle ongeviruslijders, ik voel me bij het schrijven van deze nieuwsbrief nu zelf Carol Sturka.

In New York is sinds januari van dit jaar congestion pricing ingevoerd, een soort rekeningrijden+ waarbij tol duurder is op drukke tijden, onder andere om mensen aan te zetten tot het gebruik van OV wat in New York natuurlijk heel goed mogelijk is. En het helpt, aldus onderzoek van Cornell University:

In the first six months of the program, air pollution – in the form of particulate matter 2.5 micrometers and smaller – dropped by 22% in the Congestion Relief Zone (CRZ)

En dan nog even deze ongekende eensgezindheid in de Tweede Kamer. Alle 150 Kamerleden hebben ingestemd met een motie die universiteiten en hogescholen ertoe moet aanzetten om onafhankelijker te worden van big tech!

Slecht nieuws

Chatbots kunnen mensen overtuigen om op andere partijen te stemmen, maar hun output is (verrassing!) niet altijd correct, zeker niet als het over rechtse thema's gaat, zo schrijft Nature.

En dat is niet de enige technologische inmenging, lezen we bij RTL. Ook bots en trollen blijven een probleem en hebben in de laatste Nederlandse verkiezingen "uiterst rechtse en anti-institutionele standpunten populairder laten lijken dan ze waarschijnlijk zijn"

En dan als afsluiter het droevigste nieuws van de week... DUO heeft becijferd dat blijkt dat meiden in het basisonderwijs vaker een lager schooladvies krijgen dan jongens, en dat ligt niet aan hun intelligentie. De kans dat een jongen een hoger advies krijgt dan een meisje met verder gelijke kenmerken ligt 4,9 procentpunt hoger.

Dit is nu precies die onderlaag die zo moeilijk te veranderen is, want er is geen wet die we kunnen aanpassen om dit onrecht op te lossen, dat is een complexe combinatie van acties van ouders, leraren, andere volwassenen en de media. De media waarin bijvoorbeeld niet alleen minder vrouwen in beeld komen, maar ze ook nog eens andersoortige verhalen vertellen, meer over hun ervaringen en minder over hun expertise.

Gelukkig heeft VHTO nog wat fijne tips bij het nieuws!

Geniet van je boterham!

English

Making is beautiful

If there is one statement that describes 2025 for me it is:

The secret of quality is love

Even though the quote itself is from 2016. And this week, I saw another absolutely amazing piece in the New York Times that beautifully drives this point home.

The piece itself is beautifully designed; you start reading and then scroll past videos that complement the story. But the subject matter also is one big ode to craftsmanship and love for an unexpected object: the typewriter.

This is how you can use the digital world to tell stories; this is more than paper, more than video, but something entirely its own. How unfortunate that pieces in the digital world are often just a computer version of a static piece.

But how wonderful that in the (not too distant) future, students will also learn how to create digitally, because... drum roll!!!!!

The new Dutch learning goals for digital literacy have been approved by the Tweede Kamer (Parliament), learning goals that I also had the privilege of helping to write in 2022-2023. All students in the lower grades of secondary school will soon have to work on these things (and they will also do similar things in primary school).

I will probably come back to goals 21 and 23, in which AI plays a major role, in another edition, but for now I'm going to focus on goal 22, because it fits so well with that typewriter piece. Not everyone was enthusiastic about the core objectives; there was even a Dutch website opposing the goals, full of, hilariously, AI images. "Students must create ‘digital products’.” was the criticism "But it never says why."

Of course, that's easily refutable nonsense, because we do write about the why:

Students learn to look critically at digital technology and digital media, to understand them and to adapt their actions accordingly. They also learn that it is possible to influence the development of digital technology and digital media.

But if this is not clear enough, let the magnificent typewriters convince you. I want students to be able to express their thoughts, stories, and plans in such beautiful digital forms, in addition to posters, presentations, and plays.

As I read in this wonderful (albeit somewhat belated) obituary of writer Abigail McGrath in Harper's Bazaar, art is a gateway to another world.

Perhaps this will be my slogan for 2026!

Oh, and speaking of 2026... The Dutch Stimuleringsfonds voor de Journalistiek (Journalism Stimulation Fund) asked twelve journalists and other experts what their predictions and wishes are, and I am also included with a beautiful illustration by Chuan Ming Ong.

Reader question without an answer!

I received a great question from reader Niels, IT specialist at an Amsterdam-based educational organization, to which I don't know the answer either, so I'm sharing it here (slightly shortened). Incidentally, it's not just a question, but also a kind of sign of the times.

In response to the AI Act, I am looking for a down-to-earth basic AI literacy training course for my colleagues. The first results on Google when searching for “AI literacy training” are those of the National AI Course Basic Diploma in AI Literacy, which looks like a nice website with good videos. But I became suspicious when I saw the list of sponsors, and when I took the basic course, I was shocked by how commercial it is. For example, these three experts in particular have their say, but they are not exactly independent:

Rob Elsinga, National Technology Officer (NTO) at Microsoft Netherlands

Claire Zitman - Director of AI Projects at KickstartAI

Onno Zoeter - Head of Booking AI Research at Booking.com

It's a shame, because I had high expectations. With a name like “The National AI Course,” you'd think it would be a neutral government training program. Especially since it's also mentioned by the government itself on What you need to know about AI literacy - Digital Government

I also looked at the AI and Ethics training course on the same site. This one is a lot stronger (much more contemplative), but mainly in-depth and not very practical. It also covers social media, monopolies, and the rule of law. For now, I'm looking for a basic AI literacy training course.

Another high ranking result on Google is https://ai-geletterdheidcursus.nl/, but this turns out to be from Copilot Academy, which is deeply involved in Microsoft training courses Microsoft Copilot Training in the Netherlands | Copilot Academy. If their name didn't give it away, you would have no idea.

If you have a tip for Niels, I'd love to hear it, as it's also very relevant for other readers, of course. But as I said, it also says a lot about the world we live in today. The free internet full of personal blogs, free access to knowledge from public institutions such as libraries or broadcasters, that's no longer there.

Everything is commercial, the entire internet is Brawndo, while we are just longing for a sip of fresh water.

So there might be a market (oh, the irony, I know) for a good, more neutral, non-profit AI course.

A left-wing/progressive view of AI

Where are the days when universities and students were progressive and companies and politics were conservative?

This is what Jeroen van Glabbeek, CEO of telecom company CM, writes on LinkedIn. Or rather, telecom company—if you look at their website, you'll see that the former text message seller is now fully committed to AI:

CM.com's AI-powered engagement platform helps you engage customers through AI Agents, unified data, and real-time communication across marketing, service, and sales.

When I read texts like this, I really think: what does this say? Where is Japke-D? That woman must be having the time of her life in this bubble. I can read it 10 times and still not know what kind of company this is, even though I know the approximate meaning of most of the words in this sentence.

Anyway, van Glabbeek is not the only one who is surprised by the lack of enthusiasm for AI on the left. The left-wing blog Jacobin, which, according to its own statement, "makes the ideas of the intellectual tradition of analytical Marxism accessible to the general public", also piles onto the left. Because, as Savriël Dillingh, a PhD candidate in economics at Erasmus University, writes, AI you don't hate AI, you hate capitalism.

Now, of course, I wholeheartedly agree with that, but Dillingh misses a few relevant points. But before I go into that further, perhaps we should define what the left is, or at least what it means to me. Because the left unites different kinds of people and views, which sometimes contradict each other. But just as with good food or beautiful music, yes, taste plays a role, but there is also something like a part of reality in which most people prefer fresh apple pie to soggy fries, and Joni Mitchell to Eurodance.

For me, being left-wing means working towards for a world with more equality. Traditionally, the left wing has primarily represented the working class, striving for equality between workers and factory owners. Why should the former earn less and have less say than the latter? That ideal of equality then spread to women's issues: why shouldn't women be allowed to vote and study? Why do men work outside the home with the accompanying status, financial security, and fun that goes with it, and women don't? Why isn't the care of children and the elderly more fairly distributed?

The progress that the left advocates (or, in my opinion, should advocate) is not technological progress, not progress for progress's sake, but progress away from the inequality that has developed in our society over many years. Similarly, what conservatives want to preserve is often in the realm of traditional role patterns and regulations.

And this is precisely where the problem of the contemporary left lies: we have won. I know it doesn't feel like it right now, and I regularly sit at the dinner table, fuming, telling my husband what is wrong, unfair, and ugly in this timeline, but I will be unusually positive and point this out.

Women can vote, study, and become professors (we are at 30%, according to LNVH this week). And the baker's son can study, is able to study, and does so. The enormous increase in the number of students in higher education—in 1990, 180,000 people were studying in the Netherlands, in 2000 it was 230,000, and in 2014 it was already 255,000 —is of course not attributable to the fact that we have all become smarter, but is the effect of making school more accessible and fairer, because this increase is mainly due to the increase in the number of female students in higher education. The percentage of women rose from 42% in 1990 to 51% in 2014.

So we can say that we have succeeded, and it is precisely this that has removed the unifying narrative of inequality. Because the narrative of the old left was: Look at that injustice! That rule that women are not allowed to have a bank account must be abolished. If we want everyone to be able to study, it must be affordable, so we must introduce student financing.

The top layer of problems has been solved, and the things we now have to point out are so invisible that they become unmentionable. As Christien Brinkgreve writes in Beladen Huis (what a book, by the way, thanks to my mom for the reading tip, I will definitely write more about it later):

Years of feminist struggle have left this deep layer virtually intact. [...] It is a different layer than that of laws and rules, more elusive, more tenacious (translated from Dutch)

So in this world, we must make more effort to name the unfairness, and we must do so in a world where our spirit, as A.R. Moxon calls it, is trapped by the idea that the world is fair and that people therefore get what they deserve. The story of the American Dream is also the narrative we cling to in the Netherlands: with hard work, you will get there, because the real barriers have been removed. Stories about that one woman, Moroccan, Surinamese, wheelchair user, etc. who did succeed are told and celebrated.

A CEO who earns 200 times as much as people in the factory? They should have worked harder. A woman who doesn't make it in science because she is also raising children? She is not smart and driven enough. Nothing stood in her way, right? There are now more female than male students, aren't there?

In a world where the new left no longer has a clear narrative, it is very difficult for the left to relate to the world, and therefore to AI. Is it a means of achieving equality between people, or is it not? And if it is not, what are we against? Algorithms? Big tech? Extraction?

There is no clear opposition, and then you have to ask yourself: Do left-wing people, as Savriël Dillingh writes, actually hate capitalism? When I see the enthusiasm with which the left embraces right-wing ideals such as productivity and growth, I think there is sufficient reason to doubt this.

Can AI think? The sequel

There is evidence for AI Consciousness, and not next week, no, right now, according to this roaring headline by Cameron Berg in AI Frontiers, where "expert dialogue and debate on the impacts of artificial intelligence" takes place.

Or rather, if we read the subtitle, it immediately becomes more nuanced: "A growing body of evidence means it’s no longer tenable to dismiss the possibility that frontier AIs are conscious."

Ah yes, we don't know yet, but there is growing evidence that we can no longer really defend simply dismissing AI consciousness. These are endless semantic games, starting with the lack of a definition, but there is still a lot to say about it:

Defining consciousness.

“Consciousness” is a notoriously slippery concept, so it’s important to be explicit about what I mean. I am referring to the capacity for subjective, qualitative experience. When a system processes information, is there something it is like, internally, to be that system beyond the merely mechanical? Does it have its own internal point of view? In short: are the lights on? (original emphasis).

No, but seriously, what am I reading? "beyond the merely mechanical" Um, neither a computer nor a human brain is mechanical... And are the lights on? Do I have an LED in my head? It's so tempting to refute such a piece of (nonsense) sentence by sentence, but that's exactly what such an author wants: to stimulate discussion, to fuel the debate.

And for a long time, I thought I could verbally pull off the mask. Come on, folks at Anthropic, are you seriously talking about the soul of Claude? Are you on drugs?

But I'm not falling for it anymore, because it's pointless. If you can see it for yourself, you don't need me, and do you find this impressive? Then there's nothing I can say to change your mind, and besides, you wouldn't have subscribed to this newsletter anyway.

I find it much more interesting to unravel the thought processes of people from this corner, because once you understand them, you can see the nonsense on a much deeper level, and you don't have to keep dealing with random thoughts. Two things always stand out in their thought processes:

A deep-rooted discomfort with faith

Okay, this sounds out there, I know, but bear with me. The question of whether a computer can think is, at its deepest level, a question of faith. Do you believe that a human being is more than a collection of cells that calculate? The article by Anthropic mentions this itself:

We believe Claude may have functional emotions in some sense (emphasis mine)

Disagreeing about faith is older than time, and totally fine.

I don't believe Claude has emotions, personally, because I think people have a “something”; a unique combination of your genes, your environment, all your experiences and knowledge, that makes you who you are. You don't even have to believe that this something is a soul given by a god to believe that every human being is unique. You only have to watch a small child grow up and slowly develop its own character to see that this is a unique human being in the making, different from all other people.

But "big tech" people [[11]] generally don't believe that; they believe, like Michiel Bakker and Cameron Berg, that humans are computers. Now, there are practical reasons to question that. For example, new research shows that your intestines have a strong influence on your mental state. Even if you believe that Claude has emotions, they are very different from the emotions of people with intestines. But let's say that in the distant future, we develop technology that allows us to simulate the intestinal flora of robots, then perhaps they will have similar emotions.

In that world or in this one, we don't know if a machine has a soul, or could have one in the future. All we can do is accept differences in our beliefs. I believe in the soul and you don't. No biggie, in itself.

But now comes the problem: the subculture that thinks this way has grown up with a deep distrust of faith. Faith is not an acceptable way to conduct or end a debate. The current Silicon Valley subculture has strong roots in New Atheism, the movement from the early 2000s that placed rationality above faith.

But the anti-faith vibe goes back much further, of course. I wrote earlier about the hierarchy of sciences, in which mathematics, with its pure proofs and reasoning, stands far above other ways of thinking. A computer science degree ensures, as Joseph Weizenbam said, that you can only think in the scientific way:

I am constantly confronted by students, some of whom have already rejected all ways but the scientific to come to know the world, and who seek only a deeper, more dogmatic indoctrination in that faith (although that word is no longer in their vocabulary).

So the idea that they have to admit that something they think ultimately rests on believing or not believing something causes a short circuit. The only way to convince others, as well as yourself, is to construct arguments and present evidence. It is no coincidence that the word ‘evidence’ appears 20 times in Cameron Berg's piece, and that you are bombarded with studies on self-awareness, pain avoidance, and attention: behavior that people ultimately attribute to computer output.

It always reminds me of the Heider-Simmel Illusion. If you're not familiar with it, check out this video.

Isn't it incredible that you immediately attribute emotions and motives to those little figures? They are angry and afraid, they flee, they destroy, they hide. And that's even though you know you're looking at cut-out pieces of paper! No wonder, then, that we also start thinking about emotions when we encounter something that sounds a lot more complicated.

And then there's the evidence that, according to the article "points toward consciousness-like processes in AI systems"

That evidence, according to research by The Oxford Internet Institute, among others, is often not that solid. Many benchmarks, datasets used to test what AI can do, "fail to define what exactly they aim to test"—which is understandable when you see how poorly AI goals are usually framed everywhere. And it's not just a few mistakes here and there, no:

However, roughly half of the benchmarks examined in the study fail to clearly define the concepts they purport to measure, casting doubt on benchmarks' ability to yield useful information about the AI models being tested.

And that idea isn't all that new, by the way. In 2021 (i.e., before the current ChatGPT hype), Emily M. Bender, with her deadpan humor, already referred to such benchmarks as "Everything in the Whole Wide World Benchmarks" not on her blog, but at NEURIPS, the premier AI conference.

Identification with machines

The other part of the worldview is a deep-rooted affinity with machines, so deep that it surpasses affinity with other people, especially people who are not like them. Let this sentence sink in for a moment.

Failing to recognize genuine AI consciousness means permitting suffering on an industrial scale.

If we do not take into account the idea that AI has consciousness, then we are permitting suffering, even on an industrial scale.

Even if you believe that to be true, and that AI can get bored, angry, or fall in love just like humans, you still have to see that suffering in relation to people who already exist in the real world.

People who have to watch beheadings or child pornography for a pittance so that AI doesn't show it to you.

People who get cancer because they live near a data center.

People, even children, who extract cobalt and copper from the ground.

It takes a very special kind of person to think about the possible suffering of AI computers and not about the undeniable suffering that AI already causes in humans.

[[11]]: Not everyone who works for a large tech company thinks this way, of course. But it's about the general mindset: what can you say in Silicon Valley and the surrounding area without them looking at you strangely?

The myth of two sigma

Much educational innovation is based on the idea that students will learn with technology of their own free will and completely independently, including, for example, the fantasy of Amazon's Werner Vogels, who, as he does every year, wrote a prediction for the coming year.

That idea is very easy to refute, because even we adult learners hardly use all the knowledge available on the internet to really learn; we prefer to watch cat videos or influencers. The best thing the internet has produced in terms of learning is DuoLingo, which tries to entice you to learn with points and streaks, and if that doesn't work, it resorts to blackmail and turns the cheerful logo into an owl corpse surrounded by virtual flies.

It just doesn't work. Who doesn't know someone with a huge streak but little real knowledge?

Everyone knows that if you really want to learn something, you take lessons. Just the “pressure” of having to go somewhere makes you do it, and your investment in money makes you stick to your intention.

And fair enough! You already have so much to do in life, isn't it much nicer to relax on the couch watching Netflix than having to study in the evening? Learning is tough, you have to cram, and you are constantly confronted with your own ignorance—I proudly showed my students this week my knowledge of Arabic, and after a year and a half of lessons, I still confuse the ta and the ya. If we, adults with time and well-developed metacognitive skills, don't use the internet (or books, for that matter) en masse to become smarter, how on earth can we expect teenagers to do so?

Study after study after study shows that teenagers don't. Projects in which laptops were handed out so that children could learn to program failed miserably; children used them to, surprise surprise, watch videos and listen to music. I wrote earlier about the book Charisma Machine, which described this so fantastically, and if you don't feel like reading a whole book, here is a recent paper that describes roughly the same thing. Don't feel like reading a whole paper? If you only have the abstract, that's enough.

Following schools over time, we find no significant effects on academic performance but some evidence of negative effects on grade progression. Following students over time, we find no significant effects on primary and secondary completion, academic performance in secondary school, or university enrollment.

This study was serious, following 531 children for up to ten years after the pilot!

The examples are endless. Last month, a paper was published showing that having students watch videos instead of attending actual lectures (nice and efficient!) does not help. In Munich, scientists looked at two versions of the same course, one with actual lectures and one with videos. Other than that, the courses were as similar as possible. And unfortunately, students who watched the videos performed 11% worse (0.44 standard deviation difference), and that difference was even greater for students who did poorly on the first test. And what was the main reason for that? Well, only 25% of the students watched the videos at all! And the students who did watch them did not do so throughout the semester, but, unsurprisingly, in the last few weeks before the test.

So instead of learning a little each week, with repetition, review, and testing of knowledge, they crammed everything in the last few weeks, which of course does not work.

Yet this prediction resurfaces with every educational innovation, because, well, what if it works? If it didn't work with laptops, and it didn't work with MOOCs and flipping the classroom, now we're doing it again with AI, and not just a little, but big time.

Why is this myth so persistent?

One reason for this can be found in a well-known paper by the well-known scientist Bloom (of taxonomy fame) on the two-sigma problem. When a student receives one-on-one tutoring, they perform up to two standard deviations (that's the two sigma) better than a student in a classroom. That's the dream, if only we could offer that to every child! This is where the worldview of the computer nerd comes into play again. Because what you could conclude from this is that it is the human-to-human relationship that drives performance. That a tutor who knows you, knows where you stand, creates material especially for you, and encourages you to learn is the secret sauce. This also corresponds well with the above result about the videos, because apparently going to college, where someone has come to stand in front of the class especially for you, who might say, “Hey, great to see you again, Saskia,” is different from clicking on a video. But that's not generally the conclusion of techbros. They read this research and think that what's special about that situation is the (personalized) knowledge that's being transferred. They think they can replicate that part without the human behind it. And well, that doesn't help.

But if you think this dehumanization is the biggest problem, you're wrong; there's another idea at play here. The other reason is that, simply put, according to Ben Williamson on LinkedIn, the tech industry does not actually even like education. I would go even further: they despise school. This week, I read the newsletter of a childhood friend, a man who studied philosophy and law, who now writes without hesitation that he should have stopped studying after a year or two because he could already see that it was of no use to him.

It's consumerism at its finest, as if, as a first-year student, you can just squeeze the melons of knowledge to see if they are juicy enough for you. The subjects that benefited me the most were the ones I found the most stupid and pointless during my student days. I thought I was going to be a programmer, so statistics felt pointless to me, especially since the book we were taught from at the technical university was the same for all courses and was therefore full of examples about factories producing screws that were too small. Years later, as a scientist, I really benefited from some basic statistical knowledge...! I did enjoy philosophy of science—I still remember my utter bewilderment when the teacher explained that the difference between 1 and 2 meters is very different from that between 1 and 2 degrees—but I didn't find this kind of trivia useful at all. Of course, this was partly due to the Tema sucks dynamic described earlier. Only now, twenty-five years later, do I appreciate the value of philosophy of science, and ask me again in 10 years and maybe I'll think differently. So saying now that you should have stopped is also admitting that you will never change your mind about how you view knowledge, which is sad. I will be happy if, in 10 years' time, I look at the knowledge I have in a different way, and the most beautiful emails I receive from students are when they say that they didn't understand my subject when they took it and only did so much later. The fact that you can teach a student something they don't want to learn at all is a sign of craftsmanship. An app cannot do that by definition, because as a student you have to start it up voluntarily, and you don't do that if you don't have to. And that you teach them in such a way that it matures long enough for them to link it to new knowledge later on.

Take that, Duo Owl, you'll probably never get a thank you email 10 years later.

Faux-to-correct

AI, apparently it's also in the map that Strava uses (I was too lazy to look up what they use). For people who don't live around here, Aalsmeer is located roughly where Bad News is in this newsletter.

Good news

My husband had already watched two episodes and then he insisted I watch them too. He was even willing to rewatch the first two episodes, and well, he was not wrong! What a show, Pluribus! If you ask me, it's an undiluted dig at all non-virus sufferers. Writing this newsletter, I now feel like Carol Sturka myself.

In January of this year, New York introduced congestion pricing, a kind of road pricing system in which tolls are more expensive during busy times, partly to encourage people to use public transportation, which is of course very possible in New York. And it helps, according to research by Cornell University:

In the first six months of the program, air pollution – in the form of particulate matter 2.5 micrometers and smaller – dropped by 22% in the Congestion Relief Zone (CRZ).

And then there is this unprecedented unanimity in the House of Representatives. All 150 members of parliament have agreed to a motion that should encourage universities and colleges to become more independent from big tech!

Bad news

Chatbots can convince people to vote for other parties, but their output is (surprise!) not always correct, especially when it comes to right-wing issues, according to Nature.

And that's not the only technological interference, according to RTL. Bots and trolls also remain a problem and in the last Dutch elections "made far-right and anti-institutional views appear more popular than they probably are".

And finally, the saddest news of the week... DUO has calculated that it appears that girls in primary education are more likely to receive lower school recommendations than boys, and that is not due to their intelligence. The chance that a boy will receive a higher recommendation than a girl with otherwise similar characteristics is 4.9 percentage points higher.

This is precisely the underlying layer that is so difficult to change, because there is no law we can amend to resolve this injustice; it is a complex combination of actions by parents, teachers, other adults, and the media. The media, for example, not only features fewer women, but also tells different kinds of stories about them, more about their experiences and less about their expertise.

Fortunately, VHTO has some great tips for the news (in Dutch)!

Enjoy your sandwich!

Member discussion