AI in week 45

Hallo lieve lezers! (before I forget, scroll down, or use /#english to visit the English translation right away!)

Het was me het weekje wel zeg! Was ik maandag, toen mijn stuk in Trouw verscheen nog in Zurich voor een lezing over AI, donderdag leidde ik een debat over AI op de UvA in, vrijdag gaf ik een lezing bij de uitreiking van de nationale prijs onderwijsjournalistiek, gisteren stond op het podium bij Jim en Dolf Jansen en ik was net (wie weet heb je het al gezien!) op de buis bij Buitenhof.

U snapt het, dit wordt echt een korte nieuwsbrief, ik ga het houden bij de stukken die deze week al verschenen, en wat daar verder nog over te zeggen is.

Gooi AI de klas uit

Voor Trouw schreef ik een stuk getiteld "Gooi AI de klas uit" [[1]], en de reacties... het was me wat. Mensen die zelf niet voor een krant schrijven weten dit vaak niet, maar columnisten kiezen eigenlijk nooit hun eigen headlines. De kop "Gooi AI de klas uit" is dan ook niet van mijn hand, en ik had 'm denk ik zelf anders gekozen als ik had voorzien wat voor een gedoe dit weer zou opleveren.

Niet omdat ik het er niet mee eens ben, het vangt wel ongeveer wat ik zeg, maar rood wordt het mensen blijkbaar voor de ogen als je suggereert dat we AI niet hoeven te gebruiken. Daarover ging mijn stuk in Volkskrant dan weer, zie verderop.

Eén opdeling, die ik ken van Bas Hummel, die ik heel zinnig vind is verschil tussen leren over AI en leren met AI en leren verstoord door AI.

Leren over AI. Vaak denken mensen (of zeggen ze dat ze denken) dat ik doe alsof AI er niet is, en leerlingen er dus ook niets over mee wil geven. Ik vind leren over AI cruciaal, recent onderzoek laat immers zien dat hoe minder je van AI weet, hoe vaker je het gebruikt en ik geef dus ook veel les over AI.

We lezen er stukken over, we praten erover, soms laat ik ze zelfs, als ik meekijk en oplet, iets opzoeken met AI en de resultaten met elkaar vergelijken. Leren over AI kan heel goed met AI. Misschien, zo ver wil ik nog best gaan, kan leren over AI, alleen door ook gedoseerd met AI te werken. Maar let op, ik bedoel niet dat ze zelf dingen op moeten zoeken en dan leerlingen zelf te laten ontdekken of ze er iets van opsteken, of ze de uitvoer laten controleren! Als je punt is dat er vaak verkeerde uitvoer uitkomt (en dat is zo, zelfs Altman zegt dat zelf) dan is het veel effectiever om zelf als docent een goed "fout" stuk te genereren, en dat met elkaar te bespreken. 30x half-verkeerde informatie die ze moeten controleren met de misschien machien, dat is geen doen.

Leren met AI. Dan hebben we nog leren met AI, daarmee bedoel ik leren in een wereld waarin AI er is. Rekenschap geven als docent aan het feit, of we dit nu leuk vinden of niet, waarin AI er is. Dat betekent dat als we leerlingen laten zoeken, dat we er rekening mee meoten houden dat ze met hallucinaties aankomen. En anders dan vroeger, toen we nog konden zeggen dat Harry's webhoekje geen goede bron was en of ze even verder konden scrollen, wordt de onzin nu verpakt in de epistemische mantel van Google, en van AI, en dus lijkt het waar.

En dat betekent dat we, als we opdrachten geven, we moeten nadenken hoe we de kans verkleinen dat leerlingen en studenten een LLM gebruiken om de opdracht te maken (als dat althans niet is wat we willen). Ik zie overal dat het onderwijs daar prima op kan reageren, zo zijn mondelinge examens op veel plekken weer terug van weggeweest, en tentamens en opdrachten op papier.

Voor mij persoonlijk betekent dat dat ik leerlingen en studenten in de klas en collegezaal, tenzij expliciet toegestaan, geen computers bij de hand laat houden. Juist omdat ze thuis voortdurend op AI zitten, wil ik dat in sociale leersituaties niet. Ook verplaats ik steeds vaker de hele moeilijke dingen (lange stukken lezen, of erover nadenken) naar de klas of collegezaal. Zo is er, als ze vastlopen, iemand in de buurt, ik of een andere student, om mee te denken, sparren, of hulp te vragen.

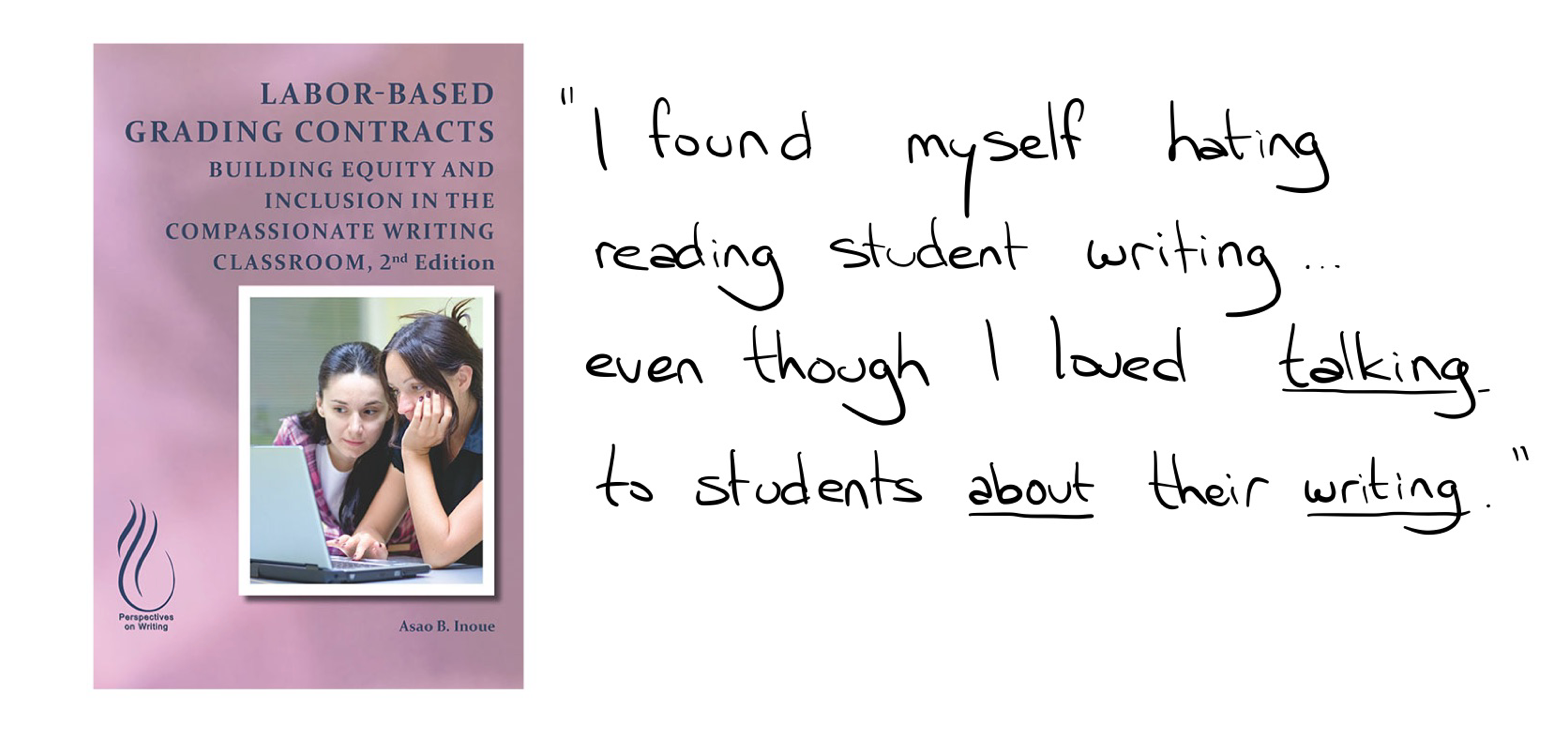

En tenslotte, zoals ik ook in Trouw schrijf, moeten we de context voor leren leuker maken en minder verplicht. Eén van de dingen waarmee ik op de universiteit aan het experimenteren ben is Labor-based grading. Ik ga daar nog wel eens in depth op in, maar het basisidee is dat studenten schrijfopdrachten krijgen, die de docent wel van feedback, maar niet van een cijfer voorziet. Je geeft ze een cijfer op basis van inzet, ik heb in mijn vak bijvoorbeeld met studenten afgesproken dat, als ze drie keer wat inleverden, ze sowieso een voldoende hadden. Je zag de druk gewoon van de ketel gaan bij ze, geen rubriks om naar te schrijven, geen cijferangst, gewoon: opschrijven wat je denkt en voelt. Ik zeg niet dat ze geen AI gebruikt hebben, neehoor, ze zaten er vast tussen en ik begrijp dat, studenten hebben het al zo druk, zeker in de lerarenopleiding waar ze 3 of soms 4 dagen lesgeven naast de ene dag dat ze bij ons college volgen. Maar ik geloof heilig dat de kans op AI gebruik afneemt als mijn verhaal naar ze toe is: ik wil oprecht weten wat jij denkt en kan, maar ik oordeel niet. Laat die spelfouten staan, ik help je ze te verbeteren, maar ik terk er geen punt voor af. Ik wil jou zien.

En een mooi praktisch punt, omdat ik studenten ook in de klas laat lezen en bediscussiëren, heb ik tijd om tijdens college na te kijken en veel ingeleverd werk onmiddellijk van feedback te voorzien. Een win-win.

Zoals de schrijver van het boek Labor-Based grading schreef (dat trouwens al van voor the chatGPT era is):

En ik denk dat veel docenten dit herkennen, ik in ieder geval wel. Door cijferen los te koppelen van feedback geven wordt nakijken opeens heel veel mooier en betekenisvoller.

Leren verstoord door AI. Dit is misschien nog het onderwerp waar ik het meest in mening verschil met de AI fans. Ja, ik weet dan ze thuis dingen aan AI vragen, ik ben niet van gisteren. Het percentage studenten dat AI gebruikte groeide van 66% vorig jaar naar 92% dit jaar. En dan kan je je, nee, dan moet je je als docent afvragen wat je daarmee doet. Ik vind het uiterst vermoeiend om steeds maar weer te moeten horen dat ik doe alsof AI er niet is (Ik zal dan ook proberen er na dit stuk niks meer over te schrijven maar gewoon hierheen te verwijzen. Ben je het grofweg met mij eens dan doe je me een enorm plezier als je dat ook doet, zodat ik niet de godganse dag in mijn eentje de dialoog aan hoef te gaan).

Dus de vraag is dan: hoe doen we dat het beste? En mijn antwoord is: ik weet het niet, en ik geloof, als wetenschapper, niet dat andere mensen dat al wel weten. Is het verstandig om prompt engineering aan te leren, als we weten dat modellen zo snel veranderen? Ik weet het niet. Moeten we steeds weer herhalen dat modellen hallucineren en dat ze alles drie keer moeten checken, of werkt dat net zo goed als zeggen dat ze op tijd naar bed moeten en niet zoveel moeten Tiktokken? Ik weet het niet. Niemand weet het.

Wat studies tot nu toe laten verschilt erg, sommige studies vinden positieve en andere weer negatieve effecten. Een metastudie concludeerde dat korte interventies meer effect laten zien dat langere (vermoedelijk omdat de nieuwigheid eraf gaat) en studenten in het hoger onderwijs hebben er meet baat bij dan kinderen op school. Wat het effect over meerdere jaren is, of decennia, daar weten we gewoon nog helemaal niks over. Niet over leeropbrengst, maar ook niet over motivatie, leerplezier, of zelfvertrouwen.

Maar er is gelukkig, een hoop dat we wel weten! Om tekst uit de misschien-machien te consumeren, moet je goed kunnen lezen. Laten we dus investeren in sterk, plezierig en goed onderbouwd leesonderwijs. Michelle van Dijk heeft talloze tips in die laatste link over hoe je dat aan kan pakken.

Om snel, zonder steeds te hoeven opzoeken en controleren, zin van onzin te scheiden, helpt het hebben van veel feitenkennis. Laten we dus investeren in sterk, plezierig en goed onderbouwd stampen.

Laten we, met andere woorden, goed onderwijs geven, zoals ik in het voorjaar ook al in NRC schreef:

En dan kom ik uit bij lesgeven zoals we dat ook voor ChatGPT deden: een capabele en bevlogen docent die in een goede volgorde en met een goed tempo kennis overdraagt, en een context waarin leerlingen veel zelf oefenen in kleine stapjes. Dat is niet wat werkt omdat we dat al decennialang doen, dat doen we al decennialang omdat het werkt.

Worst case, mocht de AI hype wegebben, heb ik mijn leerlingen een stevige basis gegeven. Wat is de worst case van all in gaan op AI? Ik weet het niet, maar jij ook niet.

En dan ga ik nog een ding zeggen voor ik even met het onderwerp AI in de klas stop, want het doet me eerlijk gezegd best wat om voortdurend door het slijk te worden gehaald als ouderwets en simpel.

Ik geloof, naast in goed onderwijs, heilig in de autonomie van de docent als professional als manier voor onderwijskwaliteit en voor werkplezier. Wil jij dus als docent wel AI gebruiken in je klas, doe dat dan. Ik zal vechten voor jouw vrijheid om dat te doen, ook als je daarbij voor mij blocking nadelen zoals bias en hallucinaties niet vindt opwegen tegen de voordelen. Lees bijvoorbeeld dit mooie en genuanceerde stuk van docent Peter Hoogendijk die al heel veel met AI doet en zijn eigen worsteling en twijfel daarbij beschrijft. Jij kent jouw context en je leerlingen het beste, en er zijn vast contexten dat het plezierig is en zinnig is om er samen mee te spelen.

Problematisch wordt het voor mij als collega's, die vaak zelf niet of nauwelijks les geven, zomaar beweren dat AI gebruiken beter is en absoluut onontbeerlijk, zonder daarvoor overtuigend bewijs te overleggen, en mij en anderen die dat niet willen steeds de maat nemen. Zulke buitengewone claims vergen buitengewoon bewijs, en dat bewijs blijft voorlopig uit. Het is niet aan ons gewone docenten om met onze leerlingen te experimenteren omdat we LLMs zelf zo cool vinden.

En weet je wie dat eigenlijk ook prima snapt? Kinderen zelf, zie deze mooie brief in NRC van Charlotte Paulus van Pauwvliet die terecht de de schrijfwedstrijd van ‘Nieuws in de klas’ won.

[[1]]: Handig, vanaf nu zet ik een linkje naar mijn stukken op mijn site! Het wordt nog eens wat met mijn organisatie talent. ..

Wat is kennis die ertoe doet?

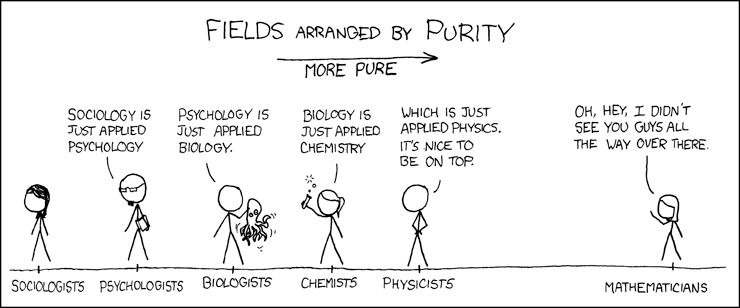

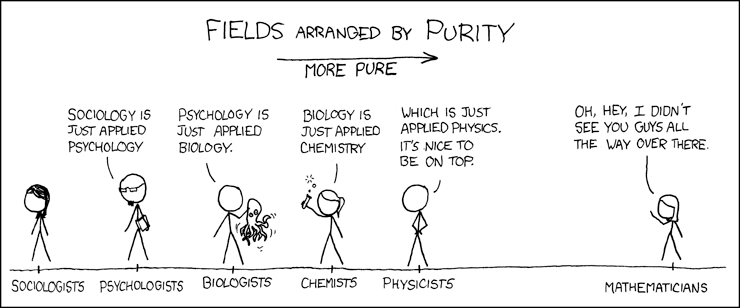

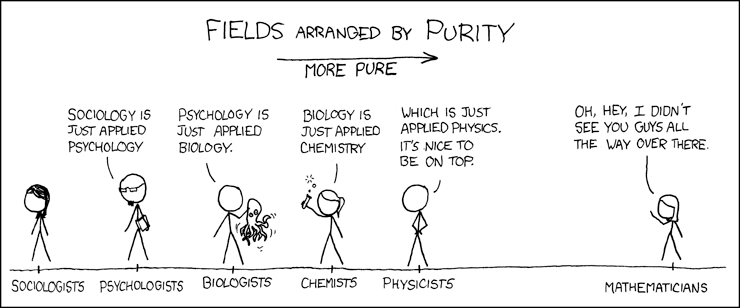

Een beetje verborgen in het stuk in Trouw stonden epistemologische overwegingen, die ik nog even extra aan uit wil stippen. Niet alle kennis wordt evenveel gewaardeerd in de wereld, misschien geeft deze hele oude XKCD dat nog het beste weer:

Ik ken dit stripje trouwens omdat het in de faculteit Wiskunde & Informatica waar ik studeerde aan de muur hing, ik weet niet meer bij welke vakgroep, helaas. Maar ondanks dat dit humor is, is de wereld van kennis wel grofweg zo georganiseerd. En dat heeft flinke implicaties, ook voor AI. Kennis die als (een bepaald soort) moeilijk gezien wordt, zoals wiskunde en het maken van algoritmes, wordt veel serieuzer genomen dan makkelijker (lijkend) werk, zoals onderzoek doen naar de impact van AI in bijvoorbeeld ethisch, sociologisch of cognitief opzicht.

En dat betekent niet alleen het voor filosofen, sociologen en cognitieve wetenschappers moeilijker is om financiering voor hun AI-onderzoek te krijgen, alhoewel dat ook al een probleem is natuurlijk, dat dat werk veel minder gedaan wordt dan het "bouwen bouwen bouwen" werk. Het betekent ook dat wetenschappers die het zachtere AI werk doen, lang niet zo vaak aan het woord zijn over AI, immers, we nodigen toch graag de slimme, indrukwekkende wetenschappers uit. Zo organiseerde de VU vorig jaar een universiteitsbrede dag over AI waarbij alledrie de sprekers (waaronder ik) uit de informatica kwamen, terwijl we natuurlijk ook allerhande andere gekwalificeerde collega's hebben.

Maar hier komt de echte kicker, het verspreiden van onderzoek volgt ook de lijnen van prestige.

prestige shapes which scientific ideas are shared and considered worthy of attention, rather than the other way around

Dus onderzoek dat minder prestigieus gezien wordt (zeg: sociologie), wordt niet vaak geciteerd in prestigieuzere gebieden (bijvoorbeeld informatica). In zekere zin is het werk dat we doen rondom AI ethiek dus "voor niks", tenzij het binnen de informatica gebeurt. Dat merkte ik zelf ook met het schrijven van mijn paper over feminisme en programmeertalen, veel van wat ik in dat paper schrijf is helemaal niet nieuw, maar was al eerder uitgebreid onderzocht en beschreven. Maar omdat mijn paper verscheen binnen de disciplinaire kaders van de informatica, kreeg het veel meer aandacht onder informatici.

Ik moest weer aan deze opdeling denken bij deze draad (beetje ingewikkeld want het is een Mastodon post over een tweet over een tweet, dus bear with me). Ik begin met de tweet over de tweet:

Something I've observed from lots of TAing is more science-oriented students like physics students tend to avoid memorization by instead understanding the content. Pre-med students tend to have a brute force approach which involves just memorizing every possible situation.

Je ziet hier, subtiel maar toch duidelijk, de hierarchie van de kennis. Kareem Carr, wiskundige aan Harvard, heeft het over het vermijden van onthouden dat natuurkundigen doen. Want dingen uit je hoofd leren, dat is natuurlijk voor dommerds. Echte slimmerds redeneren vanuit first-principles.

Een mooie reactie hierop kwam van een dokter op Mastodon, die uitlegde dat je, als je dokter bent, vaak helemaal geen tijd hebt om te gaan zitten nadenken, je moet onmiddellijk, onder hele grote tijdsdruk soms, besluiten en nemen over leven en dood. Daar heb je feitenkennis voor nodig. En, zei hij nog verder in de draad, er komen steeds nieuwe onderzoeken bij dat stofje a helpt tegen ziekte b, en daar is soms helemaal geen bekende oorzaak voor. Je moet dat dus gewoon weten.

Ik merk dat ook heel erg bij het schrijven van meer filosofische stukken, ik ben bezig met het opzetten van een argument, en opeens denk ik dan: "ik heb hier ook ooit wat over gelezen", en dan ga ik in mijn aantekeningen opzoeken waar dat was, en of dat echt mijn argument onderbouwt. Dat is een totaal andere manier van werken, waarbij je een hoofd vol feiten, namen, boeken nodig hebt, en daaruit steeds put als je iets schrijft.

En het mooie vind ik, in theorie, dat al die manieren van denken en weten en schrijven en redeneren waarde hebben, ik waardeer een breed scala aan methodes en soms wil je weten, soms redeneren, soms meten enzovoorts. Maar problematisch is dat de hierarchie ervoor zorgt dat mensen uit de betas andere soorten weten en snappen niet erkennen als waardevol, en zich verzetten tegen pogingen van anderen om ze op de problemen daarvan te wijzen.

Het is dan ook droevig maar ook weer niet verrassend trouwens dat mensen met een achtergrond in wetenschap en technologie vaker radicaliseren. Dat past bij de observaties van Weizenbaum, die ik al eerder beschreef:

I am constantly confronted by students, some of whom have already rejected all ways but the scientific to come to know the world, and who seek only a deeper, more dogmatic indoctrination in that faith (although that word is no longer in their vocabulary).

Waarom is ongeveer genoeg?

Ik kreeg een heerlijke vraag van een collega deze week: Felienne, ben jij niet amazed door wat LLMs kunnen? Is het niet magisch dat je ze volstopt met woorden en zinnen, en dat ze er dan chocola van kunnen maken? Ik wilde 'm eigenlijk hier als lezersvraag meepikken, maar het werd zo'n lekker stukkie dat ik m naar de krant heb gestuurd. Met heerlijk vondsten, al zeg ik het zelf, zoals de misschien-machien, en het ongevirus.

Verder niks aan toe te voegen, lees lekker het hele stuk.

Met dank overigens aan dit fijne stuk van de genoeg kritische, maar ook enthousiaste Bert Hubert!

Slecht nieuws

Diptheria, wereldwijd ooit bijna verbannen, maakt de laatste 15 jaar weer een fikse opmars, vooral in ontwikkelingslanden zoals Nigeria en Somalie, schrijft New York Times.

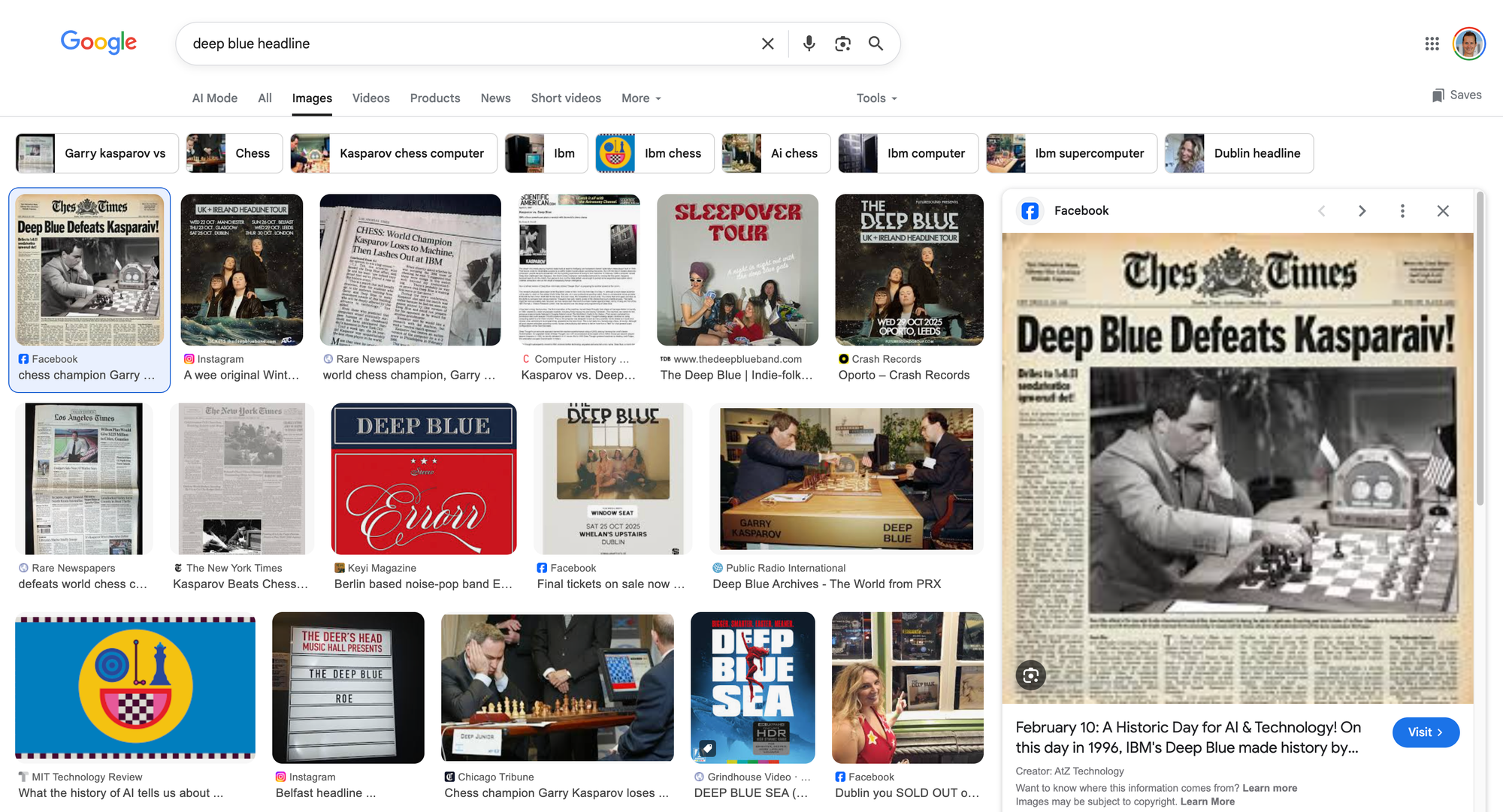

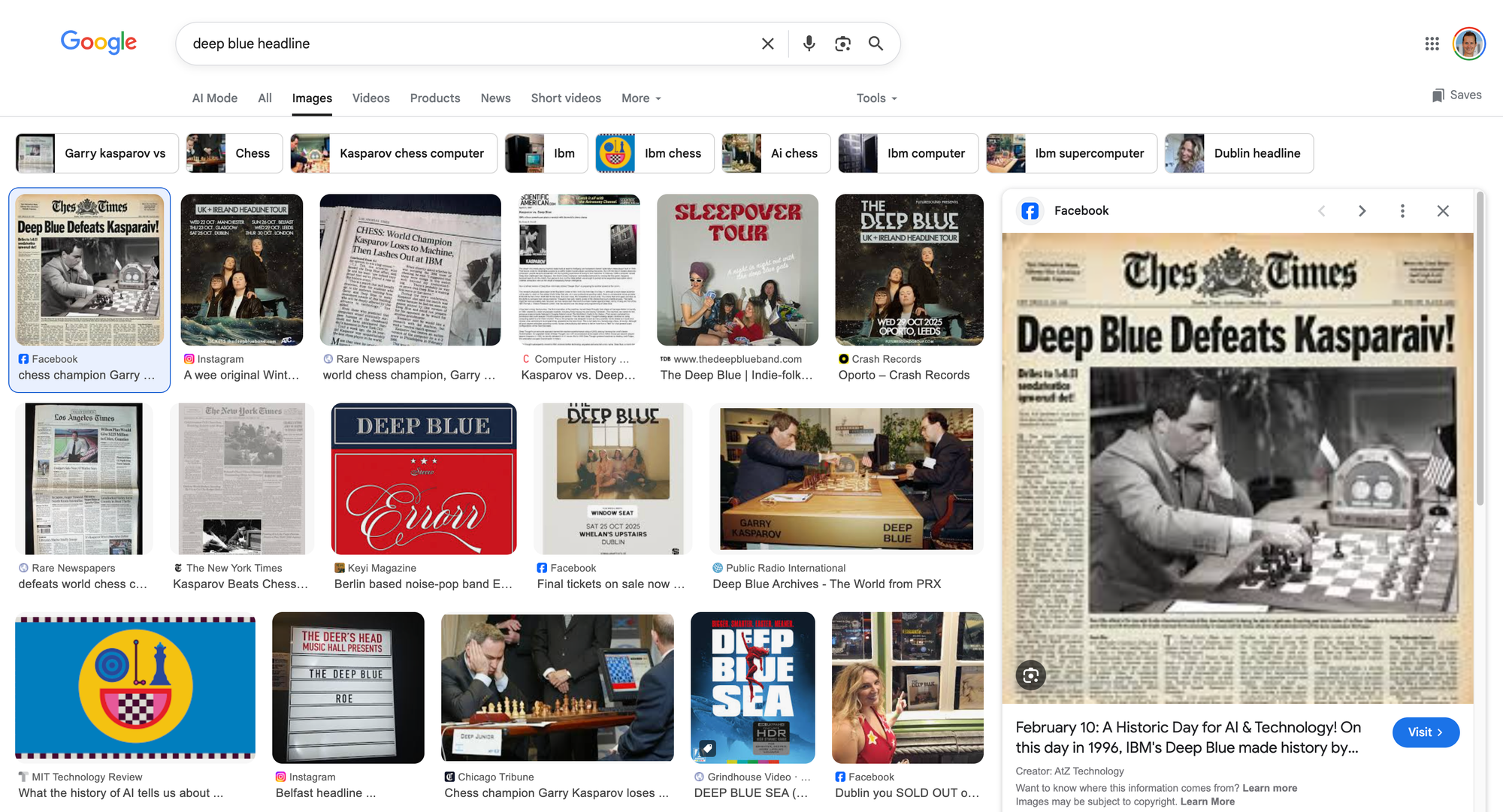

En dan nog een klein aaltje, in mijn Trouw stuk schreef ik over de winst van Deep Blue, en ik zocht, voor de bijbehorende lezing vrijdag een foto van de headline. Even vlot Googlen, en wat is de eerste hit onder Images... Kijk zelf maar even.

Waarom laten we dit toch gebeuren? Voor mij wat dit de druppel om over te stappen naar zoekmachine Ecosia, ben benieuwd hoe dit bevalt. Heb je tips voor betere zoekmachines? Ik hoor graag van je!

Goed nieuws

De vreselijke ziekte Huntington (die ik vooral ken uit de supermooie TV serie Wanted) kan met een combinatie van een operatie en gentherapie enorm vertraagd worden.

Geniet van je boterham en van het lekkere weer!

English

Well this week was quite a week! On Monday, when my article appeared in Trouw, I was still in Zurich for a lecture on AI. On Thursday, I led a debate on AI at the University of Amsterdam. On Friday, I gave a talk at the award ceremony of the Dutch award for journalism on education , and yesterday I was on stage with Jim and Dolf Jansen. And I was just (maybe you saw it already!) on Dutch TV (Buitenhof).

So, as you can imagine, this is going to be a short newsletter. I'll stick to the articles that appeared this week and what else there is to say about them.

Throw AI out of the classroom

I wrote an article for Trouw titled "Throw AI out of the classroom" [[11]], and the reactions... were quite something. People who don't write for a newspaper themselves often don't know this, but columnists don't choose their own headlines. So "Throw AI out of the classroom" is therefore not my own, and I think I would have chosen a different one if I had foreseen the kerfuffle it would create.

Not because I disagree with it—it pretty much sums up what I'm saying—but apparently people just go crazy a bit when you suggest that we don't have to use AI. That was the subject of my piece in Volkskrant, see below.

One distinction, which I learned from Bas Hummel and find very useful, is the difference between learning about AI and learning with AI and and learning disrupted by AI.

Learning about AI. People often think (or say they think) that I pretend AI doesn't exist and therefore don't want to teach students about it. I think learning about AI is crucial, as recent research shows that the less you know about AI, the more often you use it, so I teach a lot about AI.

We read articles about it, we talk about it, and sometimes, when I'm watching and paying attention, I even let them look something up with AI and compare the results with each other. Learning about AI can be done very well with AI. Perhaps, and I am willing to go that far, learning about AI is only possible by working with AI in moderation. But note that I do not mean that students should look things up themselves, and then let them discover for themselves whether they learn anything from it, or let them check the output! If your point is that incorrect output is often produced (and that is true, even Altman says so himself), then it is much more effective for teachers to generate a good "wrong" piece themselves and discuss it together. Thirty times half-incorrect information that they have to check with the maybe machine is not feasible.

Learning disrupted by AI. And then there's learning with AI, by which I mean learning in a world where AI exists. As teachers, we have to take into account the fact that, whether we like it or not, AI is here to stay. That means that when we let students search, we have to take into account that they may come up with hallucinations. And unlike in the past, when we could say that Harry's web corner wasn't a good source and ask them to scroll a little further, the nonsense is now packaged in the epistemic mantle of Google and AI, and so it seems true.

And that means that when we give assignments, we have to think about how to reduce the chance that students will use an LLM to complete the assignment (if that is not what we want, at least). I see everywhere that education is responding well to this, with oral exams making a comeback in many places, as well as exams and assignments on paper.

For me personally, this means that I do not allow students to have computers at hand in the classroom and lecture hall, unless explicitly permitted. Precisely because they are constantly using AI at home, I don't want that in social learning situations. I am also increasingly moving the really difficult things (reading long passages or thinking about them) to the classroom or lecture hall. That way, if they get stuck, there is someone nearby, me or another student, to think along with them, brainstorm, or ask for help.

And finally, as I also write in Trouw, we need to make the context for learning more fun and less compulsory. One of the things I am experimenting with at the university is Labor-based grading. I will go into this in more depth at a later date, but the basic idea is that students are given writing assignments, which the teacher provides with feedback but not with a grade. You give them a grade based on effort. In my course, for example, I agreed with the students that if they submitted three assignments, they would pass. You could see the pressure just melt away. No rubrics to write to, no fear of grades, just writing down what you think and feel. I'm not saying they didn't use AI, no, they were stuck in the middle and I understand that. Students are already so busy, especially in teacher training, where they teach three or sometimes four days a week in addition to the one day they attend our lectures. But I firmly believe that the likelihood of AI use decreases when my message to them is: I sincerely want to know what you think and what you can do, but I'm not judging. Leave those spelling mistakes in, I'll help you correct them, but I won't deduct points for them. I want to see you.

And a nice practical point, because I also let students read and discuss in class, I have time to check during class and provide a lot of immediate feedback. A win-win. As the author of the book Labor-based grading wrote (which, incidentally, predates the ChatGPT era):

And I think many teachers recognize this, I certainly do. By decoupling grading from giving feedback, checking suddenly becomes much more enjoyable and meaningful.

Learning from AI. This is perhaps the topic on which I most disagree with AI fans. Yes, I know they ask AI questions at home, I wasn't born yesterday. The percentage of students who used AI grew from 66% last year to 92% this year. And then you can, no, you must ask yourself as a teacher what you are going to do about it. I find it extremely tiring to keep hearing that I am pretending AI does not exist (I will therefore try not to write anything more about it after this piece, but just refer to this). If you roughly agree with me, you would do me a huge favor by doing the same, so that I don't have to engage in this dialogue all day long on my own).

So the question is: how do we do that best? And my answer is: I don't know, and as a scientist, I don't believe that other people know either. Is it wise to teach prompt engineering when we know that models change so quickly? I don't know. Should we keep repeating that models hallucinate and that they need to check everything three times, or is that as effective as telling them to go to bed on time and not spend so much time on TikTok? I don't know. Nobody knows.

What studies have shown so far varies greatly, with some studies finding positive effects and others finding negative effects. A meta-study concluded that short interventions are more effective than longer ones (presumably because the novelty wears off) and that students in higher education benefit more than children in school. We simply don't know anything about the effect over several years or decades. Not about learning outcomes, but also not about motivation, enjoyment of learning, or self-confidence.

Fortunately, there is a lot we do know! To consume text from the ‘maybe machine’, you need to be able to read well. So let's invest in strong, enjoyable, and well-founded reading education. Michelle van Dijk has countless tips in that last link on how to go about this.

To quickly separate sense from nonsense without having to constantly look things up and check, it helps to have a lot of factual knowledge. So let's invest in strong, enjoyable, and well-founded spaced repetition.

In other words, let's provide good education, as I wrote in the spring in NRC (Dutch):

And that brings me to teaching as we did before ChatGPT: a capable and enthusiastic teacher who transfers knowledge in the right order and at the right pace, and a context in which students practice extensively in small steps. That's not what works because we've been doing it for decades; we've been doing it for decades because it works.

Worst case scenario, if the AI hype fades away, I will have given my students a solid foundation. What is the worst case scenario of going all in on AI? I don't know, but neither do you.

And then I'm going to say one more thing before I stop talking about AI in the classroom, because, to be honest, it bothers me to be constantly dragged through the mud as old-fashioned and simple-minded.

In addition to good education, I firmly believe in the autonomy of teachers as professionals as a way to ensure educational quality and job satisfaction. So if you, as a teacher, want to use AI in your classroom, go ahead. I will fight for your freedom to do so, even if you don't think the disadvantages, such as bias and hallucinations, outweigh the advantages. For example, read this beautiful and nuanced piece by teacher Peter Hoogendijk, who uses AI extensively but describes his own struggles and doubts. You know your context and your students best, and there are certainly contexts in which it is enjoyable and meaningful to play with it together.

It becomes problematic for me when colleagues, who often teach rarely or not at all themselves, simply claim that using AI is better and absolutely indispensable, without providing convincing evidence, and constantly judge me and others who do not want to use it. Such extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, and that evidence is currently lacking. It is not up to us ordinary teachers to experiment with our students because we think LLMs are so cool.

And do you know who else understands this perfectly well? Children themselves. Like this beautiful letter in NRC by Charlotte Paulus van Pauwvliet, who won the ‘Nieuws in de klas’ writing competition, and for good reasons!

[[11]]: From now on I'll put a link to my articles on my site, although they are mostly in Dutch!

What is the knowledge that matters?

Somewhat hidden in the article in Trouw were epistemological thoughts, which I would like to highlight a bit here. Not all knowledge is valued equally in the world, perhaps this very old XKCD illustrates this best:

I know this comic because it was hanging on the wall in the Mathematics & Computer Science faculty where I studied, although I can't remember which department, unfortunately. But even though this is a joke, the world of knowledge is roughly organized in this way. And that has significant implications, including for AI. Knowledge that is considered (a certain type of) difficult, such as mathematics and creating algorithms, is taken much more seriously than easier (seeming) work, such as researching the impact of AI in, for example, ethical, sociological, or cognitive terms.

This not only means that it is more difficult for philosophers, sociologists, and cognitive scientists to obtain funding for their AI research, although that is already a problem in itself, of course, but also that this work is done much less than the “building, building, building” work. It also means that scientists who do the softer AI work are not nearly as often heard talking about AI, because we like to invite the smart, impressive scientists. Last year, for example, VU University Amsterdam organized a university-wide day on AI, where all three speakers (including me) came from computer science, even though we also have all kinds of other qualified colleagues.

But here's the real kicker: the dissemination of research also follows the lines of prestige.

prestige shapes which scientific ideas are shared and considered worthy of attention, rather than the other way around

So research that is considered less prestigious (e.g., sociology) is not often cited in more prestigious fields (e.g., computer science). In a sense, the work we do on AI ethics is therefore “for nothing”, unless it is done within computer science. I noticed this myself when writing my paper on feminism and programming languages. Much of what I write in that paper is not new at all, but had already been extensively researched and described. But because my paper appeared within the disciplinary framework of computer science, it received much more attention among computer scientists.

This thread reminded me of this division (it's a bit complicated because it's a Mastodon post about a tweet about a tweet, so bear with me). I'll start with the tweet about the tweet:

Something I've observed from lots of TAing is more science-oriented students like physics students tend to avoid memorization by instead understanding the content. Pre-med students tend to have a brute force approach which involves just memorizing every possible situation.

Here you see, subtly but clearly, the hierarchy of knowledge. Kareem Carr, a mathematician at Harvard, talks about physicists avoiding memorization. Because memorizing things is, of course, for dumb people. Real smart people reason from first principles.

A nice response to this came from a medical doctor on Mastodon, who explained that as a doctor, you often don't have time to sit down and think; you have to make decisions about life and death immediately, sometimes under enormous time pressure. For that, you need factual knowledge. And, he added further in the thread, new studies are constantly emerging that show substance A helps against disease B, and sometimes there is no known cause for this. So you just have to know that.

I notice this very much when writing more philosophical pieces. I'm in the process of constructing an argument, and suddenly I think, “I read something about this once,” and then I look it up in my notes to see where it was and whether it really supports my argument. That's a completely different way of working, where you need a head full of facts, names, books, and you constantly draw on that when you write something.

And what I find beautiful, in theory, is that all these ways of thinking and knowing and writing and reasoning have value. I appreciate a wide range of methods, and sometimes you want to know, sometimes you want to reason, sometimes you want to measure, and so on. But the problem is that the hierarchy ensures that people from the sciences do not recognize other types of knowledge and understanding as valuable, and resist attempts by others to point out the problems with this.

It is therefore sad but not surprising that people with a background in science and technology are more likely to become radicalized. This is consistent with the observations of Weizenbaum, which I described earlier:

I am constantly confronted by students, some of whom have already rejected all ways but the scientific to come to know the world, and who seek only a deeper, more dogmatic indoctrination in that faith (although that word is no longer in their vocabulary).

Why is more or less enough?

I received a wonderful question from a colleague this week: Felienne, aren't you amazed by what LLMs can do? Isn't it magical that you can fill them with words and sentences, and they can make sense of it all? I actually wanted to include it here as a reader's question, but it turned out to be such a nice piece that I sent it to the newspaper. With delightful discoveries, if I may say so myself, such as the "maybe-machine" (which in Dutch rhymes) and the "just-about-virus" (in Dutch a nice contraction of "more or less" ongeveer and virus: ongevirus )

Nothing more to add, just read the whole piece (which is in Dutch).

Hat tip, by the way, to this lovely piece by the sufficiently critical but also enthusiastic Bert Hubert!

Bad news

Diptheria, once almost eradicated worldwide, has been making a strong comeback over the past 15 years, especially in developing countries such as Nigeria and Somalia, I saw in New York Times.

And then there's another little "aaltje". In my Trouw article, I wrote about Deep Blue's victory, and I was looking for a photo of the headline for the accompanying lecture on Friday. A quick Google search, and what's the first hit under Images... See for yourself.

Why did we let this happen? For me, this was the last straw that made me switch to search engine Ecosia. I'm curious to see how I like it. Do you have any tips for better search engines? I'd love to hear from you!

Good news

The terrible disease Huntington's (which I know mainly from the wonderful TV series Wanted) can be significantly slowed down with a combination of surgery and gene therapy.

Enjoy your sandwich!

Member discussion