AI in week 40

Veel te bespreken deze week! Gelijkheid in tech, de publieke digitale ruimte, waarom vibe coding zoveel schade toebrengt aan de IT, en wel of geen interviews met AI doomers?

(As last week, scroll down, or visit my site for the English version of this newsletter.)

Waar o waar is toch de gelijkheid in tech gebleven?

Hoe denkt "Silicon Valley"? Het is iets dat mij al lang bezighoudt, ook drie weken geleden schreef ik al over mijn verbazing over de verbazing van anderen dat ze daar 'opeens' zo rechts en op de hand van Trump zijn. Een vergelijkbare verbazing las ik in Wired, in een stuk van tech-journalist Steven Levy. Het stuk is echt de leestijd niet waard, maar is interessant omdat het zo goed laat zien dat journalisten (zelfs die al langer dan ik leef over technologie schrijven) het echt niet begrijpen. Lees mee:

"What’s happened to Silicon Valley? Why did the Ayn Rand–loving heroes of tech become Donald Trump’s bootlickers?"

Op het eerste gezicht zou je het anti-overheidsdenken van Rand misschien kunnen contrasteren met het samenwerken met Trump, aka "de overheid". Maar dan kijk je niet verder dan je neus lang is, want Trump is natuurlijk geen gewone president, maar eentje die er (net als de libertariërs uit California) op uit is om de overheid te verzwakken voor eigen gewin. Levy probeert het verleden van Silicon Valley dat hij snapt, te verenigen met de huidige tijd, hetgeen hem niet lukt:

"How quickly and decisively the visionaries I chronicled aligned themselves with Trump, a man whose values violently clashed with the egalitarian impulses of the digital revolution. How did I miss that?"

Hij koppelt deze egalitaire waardes aan het ontstaan van Silicon Valley uit de jaren '60 hippiecultuur.

"Some of the first computer startups sprang from the Homebrew Computer Club, organized by an antiwar activist. The club’s moderator had led the technology wing of the Berkeley Free Speech Movement."

Tip over de hippies trouwens! Ben je net als ik veel te jong om die hippecultuur te hebben meegemaakt of het goed te snappen? Ik vond Steal this book ontzettend grappig, en het geeft echt de counter-culture goed weer, alle manieren die Hoffman beschrijft om gratis te leven zijn eigenlijk ook een soort hacken!

Maar goed even terug naar Levy. Hij mist voor mij twee belangrijke punten, en het feit dat die nog steeds onbenoemd blijven, zelfs in een stuk over hoe hij het niet begrijpt, zegt een hoop.

Levy trekt dus een lijn van de hippies naar de computernerd. Maar er is een belangrijk verschil: waar de hippies vooral filosofisch van aard waren, en hun idealen uitleefden in hun eigen leefwereld in communes en festivals, gingen de programmeurs praktisch aan de slag. De hippies moesten zich na verloop van tijd aanpassen aan de 'gewone wereld' die gemaakt is op gezinnen en kapitalisme, ze werden dus in zekere zin uiteindelijk toch veranderd door de wereld, maar de programmeurs niet, die gingen juist actief aan de slag om de wereld aan te passen aan hun ideologie, goedschiks of kwaadschiks door letterlijk te hacken. En die omgeving was perfect voor mensen die niet zozeer het veranderen van de wereld, maar juist het hacken, kraken en puzzelen zelf als allergrootste aantrekkingskracht zagen. Ethiek is iets heel anders dan hacken, zei Richard Stallman (die door Levy zelf de laatste "true hacker" genoemd werd in zijn boek uit 1984 en uitgebreid aan het woord komt) in 2002:

"Just because someone enjoys hacking does not mean he has an ethical commitment to treating other people properly. Some hackers care about ethics [...] but that is not part of being a hacker, it is a separate trait. Some stamp collectors care a lot about ethics, while other stamp collectors don't. It is the same for hackers."

Hacken is dus heel wat anders dan love, peace and understanding.

Ten tweede is er altijd al rampant sexism geweest in de hackers community. Ik citeer uit Levy's eigen boek, een hacker die vertelt over de vroegste dagen van computers in de 60s:

"“Women, even today, are considered grossly unpredictable,” one PDP-6 hacker noted, almost two decades later. “How can a hacker tolerate such an imperfect being?”"

Tsja, schrijft Levy, letterlijk, zo gek dat "there never was a star-quality female hacker. No one knows why." Ja, echt zo raar, hoe zou het kunnen joh dat vrouwen geen zin hadden om zich in deze groepen te mensen?

Dan laat hij Bill Gosper nog even aan het woord voor een verklaring.

"Even the substantial cultural bias against women getting into serious computing does not explain the utter lack of female hackers. “Cultural things are strong, but not that strong,” Gosper would later conclude, attributing the phenomenon to genetic, or “hardware,” differences."

Ik snap best dat mensen hun geheugen niet altijd alles wat ze zelf hebben geschreven kraakhelder opslaat, en 40 jaar is een lang tijd, maar dat de schrijver van bovenstaande zinnen nu opeens verbaasd achterover slaat dat er in Silicon Valley geen egalitaire cultuur bestaat... tsja?

Van wie is de digitale publieke ruimte?

Afgelopen week was ik te gast bij Stem op een vrouw om het te hebben over de digitale publieke ruimte en feminisme, hier heb ik uitgeschreven wat ik ongeveer verteld heb.

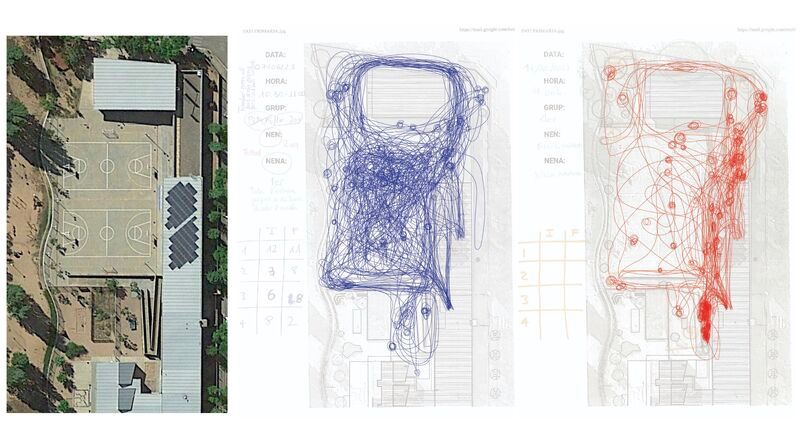

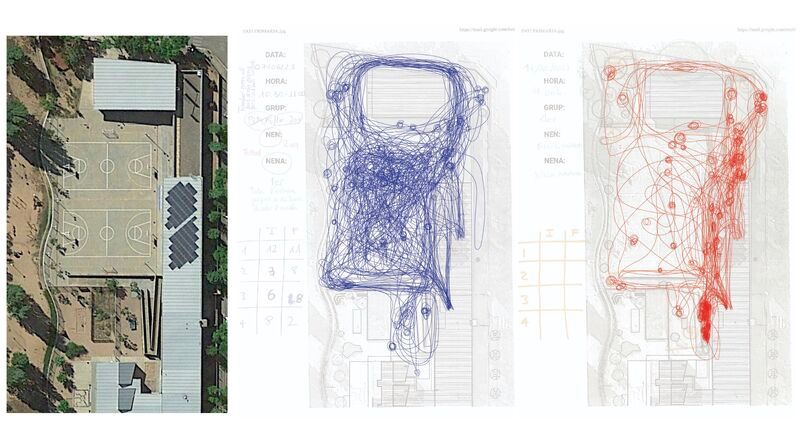

Kijk eens naar deze afbeelding, wat denk je dat de twee visualisaties weergeven? Niet meteen spieken hieronder he?

De afbeelding toont...

Een schoolplein en de paden erdoor van jongens (midden) en meisjes (rechts)

Deze afbeelding geeft pijnlijk weer hoezeer de buitenruimte gemaakt is door mannen voor jongens. Een basketbalveldje, dat is voor jongens, en meisjes moeten zich maar een beetje vermaken aan de randen. Een schoolplein zou gebalanceerder gemaakt kunnen worden, met dingen in het midden die minder expliciet opgedeeld zijn langs de lijnen van geslacht, denk aan een zandbak of een klimrek, of zelfs, ter balans, met dingen in het midden die wat meer voor meisjes zijn, turntoestellen zoals een evenwichtsbalk bijvoorbeeld. Maar we hebben wat we hebben en zo verandert de wereld maar berelangzaam.

De fysieke ruimte is helaas niet zo anders dan de digitale, ook daar moeten vrouwen en meisjes zich maar een beetje aan de rand opstellen, anders gebeurt ze nog wat. Zo liet eigen onderzoek van de Groene Amsterdammer uit 2021 zien dat maar liefst één op de 10 tweets gerichts aan vrouwelijke politici haatberichten betreft, en schreef ik vorige week nog in mijn nieuwsbrief over Zwitsers onderzoek dat laat zien dat online haat vrouwen daadwerkelijk ontmoedigt om in de politiek te gaan. En we weten al sinds jaar en dag dat de online wereld giftig is voor vrouwen, ik haalde er—maar weer eens—de analyse van GamerGate bij uit 2014 van weblog Deadspin bij, waarover ik in het voorjaar ook in Volkskrant schreef.

"What we have in Gamergate is a glimpse of how these skirmishes will unfold in the future—all the rhetorical weaponry and siegecraft of an internet comment section brought to bear on our culture, not just at the fringes but at the center. What we're seeing now is a rehearsal, where the mechanisms of a toxic and inhumane politics are being tested and improved."

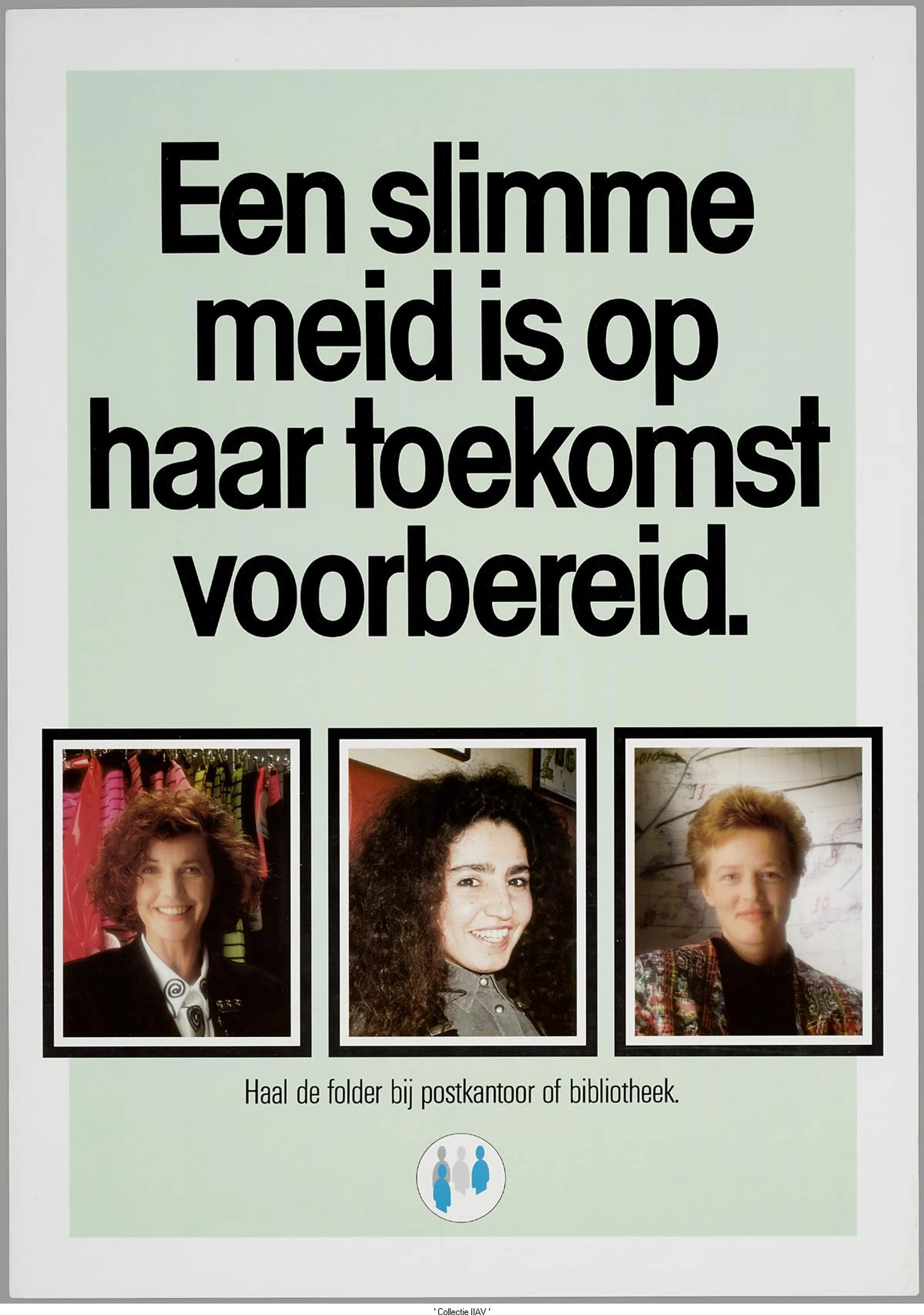

Maar deze wereld is niet de wereld die mij als kind beloofd werd. Bent u net als ik boven de 40, dan kent u toch zeker deze nog?

Tsja, wat bleek, ik was dan wel goed op toekomst voorbereid, maar die toekomst was helemaal niet zo goed op mij voorbereid, en op alle meiden en vrouwen die de techniek gingen bestormen ook niet. Ik zou de rest van de 5000 woorden van deze nieuwsbrief kunnen besteden aan voorbeelden hiervan, maar ik beperk me er tot eentje.

Toen ik solliciteerde op mijn huidige baan als hoogleraar didactiek van de informatica (een leerstoel gedeeltelijk bij gedragswetenschappen en gedeeltelijk bij informatica) werd mij gevraagd of ik wel technisch genoeg was om hoogleraar informatica te zijn. Of ik wel technisch genoeg was. Ik, iemand gepromoveerd aan de TU Delft in de software engineering, die een programmeertaal heeft gemaakt, en dan niet alleen als klein wetenschappelijk projectje, maar een groot wereldwijd open source platform. Of ik wel technisch genoeg was. Het is boos- en misselijkmakend dat iemand het kan vragen, en dat ik ook nog eens rustig moest blijven en een serieus antwoord moest formuleren, want tsja als je je koffie over een toekomstige collega gooit dan nemen ze je niet aan.

En het wrange is ook nog eens dat als ik dit verhaal aan vrouwen in mijn omgeving vertel dat hun reacties bijna altijd is: ow dat is echt zo seksistisch. Terwijl mannen soms ook reageren met verdedigende woorden, bijvoorbeeld dat die vraag eruit voortkomt dat ik ook ander onderzoek doe, bijvoorbeeld met kinderen, alsof het iets aan mijn technische vaardigheden afdoet dat ik ook nog andere vaardigheden heb. Lang verhaal kort, ik kreeg de baan wel, maar na een tijdje verhuisde ik in z'n geheel naar gedragswetenschappen, want ik had gewoon geen trek meer in de informatica [[1]].

De informatica cultuur

Van een geruime afstand tot de informatica (op de VU niet zo heel ruim, ik zit nu hemelsbreed zo'n 100 meter verderop) ging ik me als vanzelf ook met andere vragen bezighouden. Nog meer technisch onderzoek doen voelde opeens zo betekenisloos, want wat zou ik in godsvredesnaam nog meer moeten doen om er wel bij te horen? Nog een programmeertaal bedenken? Ik begon me steeds meer af te vragen waarom de informatica zo is? Waarom is het belangrijk om technisch te zijn? Deze vraag leidde als eerste tot een lijvig paper over de masculiene cultuur van mijn subveld Programming Languages.

Meer weten over dat onderzoek? Hier lees je het hele paper, maar je kan ook beginnen met een video van 10 minuten (Engels) of eentje van 40 mins (ook Engels). Ik schreef ook over dat paper in de Volkskrant in maart.

Liever een podcast? Luister dan naar deze aflevering van de Technoloog van BNR in het Nederlands met mij of eentje van Future of Programming zonder mij.

Het belangrijkste dat ik in dat werk beschreef is een idee dat ik kreeg na het lezen van een voor mij life changing paper Glaciers, gender, and science, waarin de auteurs de masculiene cultuur van de studie van gletsjers (glaciologie) beschrijven. Ik kende dit paper van Twitter, waar het in 2016 semi-viral [[2]] ging omdat mensen het bizar vonden, wat heeft feminisme nou met gletsjers te maken?! Zelfs in 2025 maken mensen zich nog erg druk over dit paper trouwens...

Maar het is een paper dat juist ontzettend veel hout snijdt, omdat het op hele concrete manier blootlegt dat kennis een sociaal construct is, dit paper is echt wel een leestip! Wat mij het meest in het oog sprong was een stuk over de liefde voor moeilijke dingen, in de glaciologie het beklimmen van onbegaanbare bergen. Dáár krijg je status van, en dus doen mensen dat, en dus hebben we veel meer informatie over "moeilijke" gletsjers dan over die bij mensen in de buurt, contra-intuitief en misschien ook niet zo nuttig, want de gletsjers in woongebieden snappen is misschien van meer praktisch nut. Die komen misschien binnenkort wel omlaag en vernielen dan hele dorpen.

Ik las en herlas en paper en concludeerde na een tijdje: dít is ook in de informatica aan de hand. Wij beklimmen dan wel geen bergen maar onze social status komt wel van complexiteit: ingewikkelde algoritmes, complexe programmeertalen, veel veel data verwerken, dat zijn de dingen die wij zien als de hoge bergen. Mensen interviewen, ethisch handelen, denken over inclusiviteit, dat zijn die lage dorpsgletsjers waar je niet dood gevonden wilt worden.

En niet alleen is de complexiteit iets dat we belangrijk vinden, het is het enige dat we belangrijk vinden. Waar sommige dokters of een advocaten misschien ook gek zijn op een supercomplexe bypassoperatie of pleidooi, zijn er ook tussen die dat beroep kiezen om mensen te helpen of uit een abstracter idee van de wereld beter maken. Die hebben we in de informatica niet, onderzoek laat zien dat de grootste reden voor het niet kiezen van de studie informatica is het belangrijk vinden van sociale verandering:

"First is the persistent negative association between social activist values

and the pursuit of computing careers; women and men who place greater

importance on helping others and effecting social change are less likely to

pursue computer science in college" Bron: Sax et al, 2016

En die complexiteit wordt dan ook nog eens gebruikt als een schild tegen alle verantwoordelijkheid. Overheden die big tech aan banden willen leggen? Die snappen er geen snars van. "Normal people and governments" zo zei Eric Schmidt, oud CEO van Google vorig jaar nog, "aren't ready". Filosofen, psychologen, linguisten of wie dan ook die niet uit de informatica komt, die snappen niets van algoritmes op social media of van AI of van LLMs en die moeten (dus) gewoon snaveltjes dicht over deze onvermijdelijke vooruitgang.

En nu zijn we dus hier, in een wereld chatbots kinderen een "beautiful suicide" beloven.

Was er een ander product geweest dat deze gevolgen had op kinderen, een energy drink, of een middeltje tegen hoofdpijn, dan was het zo uit de schappen gehaald, of daar nooit gekomen eten en medicijnen worden immers streng gereguleerd (en niet voor niets, natuurlijk). Maar op de een of andere manier vinden ingrijpen in de wereld van software te ingewikkeld om aan te beginnen, of niet goed voor innovatie in de BV Nederland. Probeer je het toch dan schreeuwen de techbros moord en brand en noemen ze je een luddite (een term die gelukkig wel terug is van weggeweest, aldus geweldige stuk van n+1 magazine)

Als je je afvroeg waarom ik er week op week zin in heb om duizenden woorden vuil te maken aan kritiek op AI, dan is dat dat deze repliek op mij maar nauwelijks van toepassing is, je kan mij niet verwijten dat ik niet goed snap hoe algoritmes of software werken, en dus horen mensen mijn verhaal anders. Heel vaak als ik spreek op scholen over AI, en vertel dat AI niet onvermijdelijk is, of intelligent, dan halen docenten opgelucht adem. Dat dachten ze zelf namelijk ook al, maar ze durven het niet te vinden omdat ze zichzelf niet vertrouwen om er genoeg van te snappen.

Zo sloot ik mijn betoog woensdag dan ook af: ook al ben je geen techneut, je weet genoeg! Ik weet genoeg van benzine-auto's om te weten dat ik er geen wil, ik hoef daarvoor helemaal niet te weten wat een bobine doet. Als jij geen software wil van een bedrijf dat "tieners die zich waardeloos, onzeker, gestrest, verslagen, bang, dom of waardeloos voelen" als product verkoopt, of extreem-rechts blijft pushen dan hoef je daar helemaal niet voor te weten hoe het precies geprogrammeerd is!

Ben je overtuigd en wil je van (Amerikaanse) big tech af, niet alleen Bert Hubert heeft een lijstje, Paris Marx ook. Maar dat dat niet altijd meevalt, beschreef Marloes de Koning geestig in NRC, "alsof je een vegaburger bestelt terwijl je een BigMac wilt".

Vibe coden de dood van programmeren?

Als dat zo is, dan hebben we dat zelf gedaan met z'n allen.

Als mensen mij vragen hoe het met mijn onderzoek gaat, dan heb ik tegenwoordig niet echt meer een pasklaar antwoord. Waar ik vroeger volop bezig was met mijn programmeertaal Hedy, en er altijd wat cools te melden was; een nieuwe feature, een nieuwe taal, ergens een studie aan het runnen, laat mijn onderzoek zich nu veel minder vangen in concrete voortgang.

Waar ik vroeger dacht dat de problemen in ons veld met programmeren op te lossen waren—als talen niet inclusief zijn, dan bouw ik ze inclusiever, case closed—richt ik me nu meer op de vraag waarom de problemen ontstaan zijn. Gedeeltelijk komt dat door de reactie op mijn werk om programmeren inclusiever te maken, bijvoorbeeld door het toelaten van Arabische of Chinese karakters en woorden. Ik dacht dat het gewoon een klein foutje was van onze community dat we die talen niet in Python, C, of Java hadden ingebouwd. Gewoon even niet aan gedacht. Ik had dus ergens (heel naïef, I know) gedacht dat als mensen Hedy in een andere taal zouden zien, ze zouden denken: ah cool, dat kunnen wij ook! Ik schreef voor de zekerheid met oud-collega Alaaeddin Swidan een paper dat uitlegt hoe je meertaligheid in je code in kan bouwen.

Echter, veel programmeurs waren helemaal niet enthousiast, au contraire! Ze vonden het te veel moeite, want "zij" kunnen toch "gewoon" Engels leren? Of ze vonden het maar storend dat de woke strijd voor gelijkheid en inclusie nu ook het ontwerp van programmeertalen bereikt had.

Dus verlegde ik langzaam maar zeker mijn focus, niet naar: hoe lossen we dit probleem op, maar: waarom is dit probleem ontstaan? Hoe is het mogelijk dat ik in mijn informatica-studie wel vijf vakken heb gevolgd over het maken van programmeertalen, maar dat niemand daarbij vertelde dat 1+1 niet in alle talen en culturen hetzelfde is? Waarom leerde we alles over de geschiedenis van C, C++, Java, ABC en PASCAL, maar niets over programmeertalen en systemen uit andere culturen, zoals experimenten uit de Sovjet-unie om een ternaire, niet binaire computer te maken. Je zou verwachten dat dat de geest van informatici zou prikkelen net als een programmeertaal met alleen maar tabs en spaties. En hoe is het mogelijk dat John von Neumann, een man persoonlijk betrokken bij het uitkiezen van doelwitten Hiroshima en Nagasaki, niet alleen uitvoerig voorkomt in onze curricula (hij is nu eenmaal bekend van de Von Neumann-architectuur), maar ook nog steeds naamgever is van een bekende IEEE-prijs? Wat zegt dat over onze normen en waarden?

Hoe je een waarom-vraag beantwoordt is veel ongrijpbaarder, hoe weet je hoe je voortgang maakt? Wat zijn de stappen om daar te komen?

Eén van de dingen waar ik veel over nadenk is over hoe we programmeren definiëren. Programmeren is een heel ongrijpbare term, het kan eigenlijk van alles betekenen. In heel oud onderzoek van mij (uit 2017, ver voor Hedy) schreef ik al hoe het proces van programmeren wel wat weg heeft van het proces van het schrijven van een boek.

Schrijven is ook een ongrijpbare term, en toch kunnen we daar prima mee omgaan. Iedereen snapt dat als ik zeg dat ik een boek aan het schrijven ben, ik daarmee niet alleen rammen op het toetsenbord bedoel, maar ook plannen, schrappen, herlezen en communiceren met een uitgever, en zelfs het geven van een lezing over mijn boek hoort er misschien wel bij.

In het programmeren echter ligt dat totaal anders. Programmeren betekent voor de meeste mensen alleen het typen van de code op de computer mee [[3]]. Als mensen horen dat je programmeur bent, dan denken ze aan ongrijpbare matrix-codes die naar beneden rollen, niet aan iemand die met een kladblok rondloopt en mensen bevraagt over hoe ze hun werk doen en hoe software daarbij zou kunnen helpen.

Dat idee komt niet uit de lucht vallen, dat zit ingebakken in je opleiding, toen ik studeerde waren er de vakken Programmeren 0 (haha, tellen begint bij 0) t/m 5, en die gingen alleen maar over codes schrijven. Dat oefenden we meestal met mini-probleempjes zoals priemgetallen uitprinten, stukken tekst omdraaien of zoeken in een lijstje. (Eigenlijk begint het zelfs al eerder, als we aan leerlingen in het vo vertellen dat wiskunde B zo heel vreselijke belangrijk is voor informatica, en door het feit dat informatica heel vaak bij wiskunde in de faculteit zit.)

Andere vakken dan puur programmeren en wiskunde komen later in je studie, en gaan dan ook op wiskundige manier, een vak over testen bijvoorbeeld gaat vaker over de technieken en frameworks van testen, dan over met mensen testen. Dat is immers later niet jouw werk, dat doet een tester! Of een vak dat iets als Requirements Engineering heet, dat klinkt heel moeilijk en technisch, maar dat is gewoon "aan mensen vragen wat ze willen". En ook dat hoef je maar zijdelings te leren hoor, want praten met klanten, dat doet een product manager wel voor jou. Jij mag lekker de hele dag codes typen!

Zo wordt de menselijkheid uit het vak gehaald, en het beeld geschapen dat programmeren heel heel moeilijk is, en dan kan je je als programmeur lekker slim voelen. De afgelopen jaren hebben de salarissen in de tech dat beeld natuurlijk ook flink ondersteund, als je zoveel kan verdienen moet je wel iets heel bijzonders kunnen.

Maar helaas pindakaas, daar komt de AI trein aan! Laat code typen nou net iets zijn waar LLMs redelijk goed in zijn (of in ieder geval heel goed in lijken!). Iedereen kan lekker aan het vibe coden, en opeens zijn er geen programmeurs meer nodig, zo waait nu de wind en opeens is de vaardigheid programmeren zo bijzonder niet meer (ook al werkt het helemaal nog niet zo). Oops. Hadden we wat meer gefocust op de menselijke kant, op echt luisteren naar wat mensen nodig hebben, dan was ons vak misschien niet zo uitgehold!

Want wat er echt moeilijk is aan een goed product maken, dan is snappen wat er in de echte wereld gebeurt en dat dan omzetten in code.

De lezersvraag: welke meningen moet je een platform geven?

Naar aanleiding van vorige week toen ik over Michiel Bakker schreef, vroeg een lezer zich af of zo'n interview eigenlijk wel een goed idee is. De journalist hoopt waarschijnlijk dat zijn stellige uitspraken (bv over mensen die machines zijn) voor zichzelf spreken, in de hoop/verwachting dat het publiek daar ook wel doorheen prikt, maar is dat ook zo?

Het is een klassiek dilemma. Geef je Baudet zuurstof, of Wilders, Trump? Of iemand als Wierd Duk? Zijn zijn invloedrijke stemmen, maar ja door een interview worden ze ook weer zichtbaarder.

Ik moest als eerste denken aan stukje uit 2012 van John Oliver, waarin hij Donald Trump smeekt me mee te doen aan de verkiezingen. Hahaha, wat zal dat lachen worden zeg. Tsja, not so funny now, denk ik, nu er letterlijk mensen van straat gegrist worden door gemaskerde ICE agenten.

Voor het grootste gedeelte is het oude adagium denk ik waar: Er is niet zoiets als slechte publiciteit. Je naam in het nieuws, in welke vorm dan ook, dat is goed voor je brand. Is het in de good old legacy media zoals Volkskrant, dan werkt het legitimerend. Een figuur als Thierry Baudet is door de media in het zadel geholpen ook al was zijn eerste tv-optreden er eentje waarin hij geweld tegen vrouwen normaliseerde. De dynamiek die toen ontstond is een goed voorbeeld van de energie die het kost om zulke standpunten te ontkrachten. Baudet mag op tv voor een groot publiek iets zeggen en vervolgens is het aan vrouwen om steeds maar weer uit te gaan leggen hoe zoiets dehumaniserend werkt en welke gevolgen het kan hebben. Het kost tijd, energie en frankly ook levensgeluk om het steeds weer te moeten gaan uitleggen waarom problematische dingen problematisch zijn, dat schreef ik in 2016 al.

Bovendien worden verkiezingen vaak niet gewonnen op meningen, maar op onderwerpen, dus als jij bepaalt wat het onderwerp van gesprek is, heb je de strijd eigenlijk al gewonnen. Dit wordt ook wel 'agenda-setting theory' genoemd. (Wilders snapt dit heel goed zo blijkt uit een goede analyze van NRC van zijn recente tweets, door nagenoeg alleen nog maar over migratie te schrijven).

Media, zo zei Bernard Cohen al in 1963, "may not be successful much of the time in telling people what to think, but it is stunningly successful in telling its readers what to think about." Gaat het in de krant voortdurend over dichtere grenzen, ook al roepen v/d Plas en Wilders dingen die staatsrechtelijk voorlopig echt onmogelijk zijn, dan is het toch weer dat onderwerp dat de klok slaat.

Andere partijen zien dat de extreme standpunten keer op keer aandacht krijgen, en die schuiven ook op, zoals Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer onlangs weer benoemde in HP/deTijd.

"Onder invloed van Wilders in het Raam van Overton zozeer naar rechts opgeschoven dat een voormalige middenpartij als de VVD aan de electorale dreiging van Wilders genoeg heeft om diens extremistische standpunten in te nemen. In zekere zin is de rol van Wilders hiermee uitgespeeld. Hij is niet meer nodig. Hij heeft al gewonnen. Zijn fascisme is mainstream geworden."

Zo hoeven de extreme partijen hun standpunten helemaal niet aan te passen, sterker nog, die kunnen dan weer verder de fringes in. Wat compromis lijkt, wordt zo een eenzijdige strijd, zo goed beschreven in het boek Very Fine People van AR Moxon: [[4]].

"Meet me in the middle, says the unjust man.

You take a step towards him, he takes a step back.

Meet me in the middle, says the unjust man."

Nu komt dat echt niet alleen door de journalistiek he? Even voor de duidelijkheid, daar kunnen we niet alleen journalisten de schuld van geven! Ook social media heeft ermee te maken, en verschillende crises zoals oorlog in Syrië, de huizen/stikstofcrisis, corona, Oekraïne die steeds weer aanleiding waren voor nieuwe discussies over grenzen en overheidsinmenging en zo weer aanleiding gaf voor het platformen van sommige meningen, hetgeen weer reacties uitlokte etc etc.

Ok, tot zo ver het punt voor het klassieke dilemma, dit heeft allemaal nog niks met AI te maken, bij AI ligt het subtiel nog wat anders. Want waar mensen bij uitspraken van Duk, Wilders of Trump, in theorie, nog zouden kunnen denken, "hé maar dit kan helemaal niet!" is dat bij een stuk over AI bijna onmogelijk.

Door de dynamiek van complexiteit (zie ook hierboven) zijn informatici erin geslaagd de "normal people" uit de discourse te weren, omdat ze niet snappen wat er staat. Een universitair docent aan MIT, tsja, die zal het toch wel weten zeker? En zijn vrienden en bekenden moeten toch ook allemaal superslim zijn? Nou, als die het allemaal ook vinden, dan is dat niet een zeer slappe appeal aan authority maar een ijzersterk punt.

En in de AI discussie weten we het simpelweg allemaal niet. Bakker zegt:

"Wij zijn uiteindelijk een biologische computer. En waarom zou een niet-biologische computer niet hetzelfde kunnen? Ik zie geen enkele fundamentele beperking."

Tsja, daar moet je hem gelijk in geven in zekere zin. Op de een of andere magische manier die we totaal niet snappen kunnen mensen dingen. We hebben wat ontrafeld, maar ook zoveel nog niet. Hoe vormt een gedachte zich? Terwijl ik dit typ gebeurt er ergens in mijn lijf, in mijn hoofd, maar nieuw onderzoek laat zien ook in andere stukken van je lijf zoals de darmen, gebeuren iets dat er uiteindelijk toe leiden dat mijn vingers letters typen op een toetsenbord. Zou je dat hele proces kunnen namaken op een computer? Misschien wel. Ik denk persoonlijk van niet, want ik denk dat er zoiets is als een ziel, iets dat jou als mens uniek maakt, een mix van je persoonlijkheid, opvoeding en je lijf, maar een ander mag gerust denken dat een computer dat inderdaad kan. Wat Bakker zegt is niet zozeer totaal van de pot gerukte onzin, als wel een geloof.

Bakker is natuurkundige. Hoe weet hij eigenlijk dat een mens een biologische computer is? Wat betekent dat woord computer daar in die zin? Doen mensen soms niet meer dan rekenen? Voelen ze niet ook emoties, stress, paniek? Kan je dingen die niet rationeel zijn, wel berekenen? Ik ben inmiddels oud genoeg om toe te geven dat veel van mijn onderzoek, en van mijn denken wordt gedreven door mijn gevoel. Ik vind het oneerlijk dat vrouwen niet mogen meedenken in de digitale wereld, dat maakt me boos, en daarom ben ik gemotiveerd om zoveel van mijn computationele power daaraan te wijden. Die gevoelens komen voort uit 25 jaar als vrouw in de IT wereld rondlopen en op die manier ervaringen opdoen die uniek voor mij zijn. Er zijn maar weinig mensen die jarenlang als (bijna) enige vrouw in een collegezaal hebben gezeten, en zijn maar weinig mensen die een programmeertaal hebben gemaakt en hebben gezien hoe boos het mensen maakt als je probeert om dat op een inclusieve manier te doen. Mijn ervaringen, gecombineerd met mijn karakter en mijn opvoeding maken dat ik dingen doe, dingen weet, dingen wil. Zelfs als je gelooft dat een computer kan denken, geloof je dan werkelijk dat computers ooit in alle soorten en maten gaan ontstaan? Het wereldbeeld dat onbenoemd blijft is hét wereldbeeld van beta, waarin kennis los staat van de weter, en waarin zo'n rekenende computer niet uniek is, maar slimmer/beter/wijzer is dan alle mensen samen. Dat zie je ook duidelijk aan uitspraken als "Waar en hoe die kracht wordt ingezet, zou door ons allemaal bepaald moeten worden." alsof er een juist antwoord is waar we gewoon even op moeten stemmen, in plaats van een veelheid aan stemmen, genders, culturen, talen, die allemaal wat anders willen. Het lijkt me uiterst onwaarschijnlijk dat veel Volkskrant-lezers dit soort dingen denken als ze die zin lezen.

En zo kunnen we doorgaan met het wetenschapsfilosofisch uitgraven van deze manier van denken want wat betekent biologisch? Nemen we ook de darmflora mee, gaan we die ook simuleren in de PC? Mogelijk, maar niet iets waar de wetenschap op dit moment de pijlen op richt. En wat te denken van menselijke voortplanting? Zo ongeveer helft van de mensheid kan nieuwe mensen maken met hun lijf, en dat is nou niet bepaald een bewust cognitief proces. Het is niet dat zwangeren in een Excelsheetje zitten bijhouden welke genen van de een of de andere ouder ze gaan kiezen, of dat ze even een wijsvingertje of een rechterlong aanmaken met pure wilskracht. Denk je even door, dan kom je toch al snel tot de conclusie dat het feit dat een computer in de denkbare toekomst geen babies gaat kunnen maken, nogal een fundamentele beperking is. Ook hier dringt zich, bij goed kijken, weer een mensbeeld op, namelijk een mensbeeld waarin alleen het denken van de mens telt als mens, als iets dat gesimuleerd moet worden. Alle andere dingen die mensen doen—poepen, zingen, seks hebben, boos worden, rouwen etc etc etc—leggen onmiddellijk die fundamentele problemen blootleggen die Bakker onder het tapijt veegt. Nogmaals, het lijkt me uiterst onwaarschijnlijk dat veel Volkskrant-lezers dit soort dingen denken als ze die zin lezen, want wat wel en niet denken is, wat wel menselijk is, is al 2000 jaar (en waarschijnlijk nog veel langer) het onderwerp van heel veel filosofie. Het is geen puzzeltje dat een programmeur even kan kraken, het is een ongoing debat met een rijkheid aan mooie, lelijke, gekke en sterke meningen.

Daarom is zo'n stuk, en deze denkwijze in het algemeen, niet geschikt voor denken in termen van: als mensen dit lezen, zien ze wel dat het onzin is. Ze zien dat iemand, die door het systeem wat we hebben gecreëerd waarin beta's aan de top van de voedselketen van slimheid staan, op een voetstuk wordt gezet en dan wordt dit mensbeeld een soort feit.

En wat er in heel veel stukken over A(G)I gebeurt is eigenlijk precies Cohen in actie. Het gesprek over AI gaat over of het nu wel of niet kan denken, of het intelligent is of superintelligent of hyperintelligent of wat ze ook maar weer voor nieuwe term hebben bedacht, en over of dat in de toekomst existentiële risico's met zich meebrengt, niet over de veelheid van problemen die AI nu al veroorzaakt!

Events

Binnenkort kun je me hier treffen:

- Op 30 oktober sta ik op het podium met John Hattie en Gert Biesta! Heel erg cool!

- 11 november spreek ik over de geschiedenis van AI in Amsterdam op de Eurostar conferentie

- Wat verder in de toekomst: Op 12 februari 2026 spreek ik op de NLT conferentie in Ede

Goed nieuws

Ok, ik was waarschijnlijk de allerlaatste die dit ontdekte maar ik heb toch nog even smakelijk gelachen toen ik hoorde dat de baas van Nintendo Amerika Doug Bowser heet!! Heeft er ooit een geestigere aptoniem bestaan dan een eindbaas die de naam heeft van een eindbaas??

Hoera, er is wat de doen aan al die CO2 in de lucht! Een Eindhovens bedrijf heeft een demonstratiemodel gemaakt dat 3 ton CO2 per jaar kan opzuigen. Carbyon belooft dat de volgende versie wel 25x zo goed zal zijn, en wel 75 ton per jaar zal gaan verwijderen, hetgeen ongeveer de uitstoot van vijf Nederlandse huishoudens is. Lekker, dat zet zoden aan de dijk.

De Nederlandse overheid (ok behalve de Belastingdienst dan, zie verderop) wordt zich steeds bewuster van de problemen van Big Tech, niet alleen de afhankelijkheid maar ook de hoge licentiekosten (voor producten die je vaak ook redelijk aardig kan vervangen door gratis open source pakketten) dus daar gaan ze nu onderzoek naar doen.

Ook de Consumentenbond mengt zich in de AI discussie, heel goed en heel terecht! Twintig van de 70 Google AI antwoorden die ze onderzochten waren volgens de "achterhaald, te stellig, te ongenuanceerd of te commercieel." Dat is opvallend zeggen ze, omdat je de feature vaak ongevraagd oppopt. Fijn dat ze wel de tip noemen om "-AI" te gebruiken, dan blijven de hallucinaties uit!

Steeds meer Amerikanen zien wedden op sportwedstrijden als slecht voor de samenleving, vooral onder jonge mannen neemt deze opvatting toe van 22% in 2022 naar bij de helft in 2025.

Ok, het is geen nieuws want het originele stuk komt al uit 2020, maar ik pik m toch mee, omdat het zo mooi is. In Finland weten ze hoe ze dakloosheid op moeten lossen, namelijk door daklozen, je raadt het niet, een huis te geven. Het is goed nieuws, maar ook ergens heel droevig natuurlijk, dat een simpele interventie op zoveel plekken, ook in Nederland, niet overwogen wordt omdat anderen zouden klagen dat het oneerlijk is, of duur, of moeilijk.

"in deze steeds meer gepolariseerde samenleving" dat hoor je overal maar is dat ook zo? Wetenschapscommunicatieheld Michel van Baal dook in de data van het CBS en zag dat vertrouwen in andere mensen én in de rechtspraak de afgelopen 12 jaar juist is toegenomen!

En als heerlijke uitsmijter, Bits of Freedom heeft hun rechtszaak tegen Meta gewonnen, gebruikers van Insta en Facebook moeten de optie krijgen om standaard een chronologische tijdslijn te kiezen (en dus niet eentje die bij iedere nieuw bezoek weer algoritmisch wordt, zoals nu). Meta krijgt twee weken om dat te fiksen, ook met oog op de verkiezingen.

Slecht nieuws

In een timing die niet maffer had kunnen uitpakken, deze week het nieuws dat re belastingdienst toch naar de Microsoft-cloud verhuist. Zo'n project loopt natuurlijk al eeuwen, maar het is toch apart dat dit wordt doorgezet terwijl digitale soevereiniteit van de VS belangrijker is dan ooit.

Schreef ik bij Goed Nieuws over hoe de nog niet gebouwde nieuwe versie van de CO2 stofzuiger de uitstoot van wel vijf Nederlandse gezinnen kan opzuigen? Helaas pindakaas, dat kost dan wel ongeveer zoveel energie als vier huishoudens... Een goed voorbeeld van hoe hypothetische technologie ons weer lekker in slaap kan sussen met "dat lossen we nog wel op".

CarpetRight is failliet en dat komt, onder andere, door een mislukt softwareproject. Het zoveelste voorbeeld van "20 jaar digitaliseren, 0 effect".

En niet alleen het klakkeloos invoeren van software is slecht voor de bedrijfsvoering dat zijn overnames door private equity ook. Onderzoek in Amerika vergelijkt ziekenhuizen die worden overgenomen met vergelijkbare en ziet in die van private equity 13% meer sterfgevallen voorkomen, voornamelijk door het ontslaan van mensen die achteraf heel nodig bleken.

Geniet van je boterham!

English

Lots going on this week! Equality in tech, the public digital space, why is vibe coding wrecking our profession, and should we platform AI doomers?

Where, o where, has equality in tech gone?

How does Silicon Valley think? It's something that has been on my mind for a long time. Three weeks ago, I wrote about my surprise at the surprise of others that they are 'suddenly' right-wing Trump fans. I read about similar surprise in Wired, in an article by tech journalist Steven Levy. The article isn't really worth reading, but it's interesting because it shows so clearly that journalists (even those who have been writing about technology longer than I've been alive) really don't understand. Levy writes:

"What's happened to Silicon Valley? Why did the Ayn Rand–loving heroes of tech become Donald Trump's bootlickers?"

At first glance, you might indeed see Rand's anti-government thinking as contrary to collaborating with Trump, aka "the government." But then further inspection of course shows that Trump is obviously not a normal president, but one who (like the California libertarians) want to weaken the government for his own gain. Levy tries to reconcile the past of Silicon Valley that he understands with the present, but fails:

"How quickly and decisively the visionaries I chronicled aligned themselves with Trump, a man whose values violently clashed with the egalitarian impulses of the digital revolution. How did I miss that?"

He links these egalitarian values to the roots of Silicon Valley in the hippie culture of the 1960s:

"Some of the first computer startups sprang from the Homebrew Computer Club, organized by an antiwar activist. The club's moderator had led the technology wing of the Berkeley Free Speech Movement."

Tip about the hippies, by the way! Are you, like me, too young to have experienced hippie culture or to really understand it? I found Steal this book incredibly funny, and it really captures the counterculture well. All the ways Hoffman describes to live for free are actually a kind of hacking!

But anyway, back to Levy. For me, he misses two important points, and the fact that they remain unmentioned, even in a piece about how he doesn't understand it, says a lot.

Levy draws a line from the hippies to the computer nerds. But there is an important difference: while the hippies were mainly philosophical in nature and lived out ideals in their own world of communes and festivals, the programmers took practical action. Over time, the hippies had to adapt to the ‘normal world’ built for single families and capitalism (reading Steal this book it becomes so obvious how many of the ideals like a groceries coop were untenable), so in a sense they were ultimately changed by the world, but the programmers were not. They actively set to work to adapt the world to their ideology by literally hacking.

And those circumstances welcomed people who were not so much interested in changing the world, but rather saw hacking, cracking, and puzzling as their greatest virtue. Ethics is very different from hacking, said Richard Stallman (who was called the last “true hacker” by Levy himself in his 1984 book and is quoted in it extensively) in 2002:

"Just because someone enjoys hacking does not mean he has an ethical commitment to treating other people properly. Some hackers care about ethics [...] but that is not part of being a hacker, it is a separate trait. Some stamp collectors care a lot about ethics, while other stamp collectors don't. It is the same for hackers."

Hacking thus is at its core very different from love, peace, and understanding.

Secondly, there has always been rampant sexism in the hacker community. I quote from Levy's own book, where an unnamed hacker us talking about the early days of computers in the 60s:

"Women, even today, are considered grossly unpredictable [...] How can a hacker tolerate such an imperfect being?"

Levy continued by remarking how absolutely weird it that “there never was a star-quality female hacker. No one knows why.” Yes, really so strange, how could it be that women didn't feel like joining these groups? Then he quotes Bill Gosper:

"Even the substantial cultural bias against women getting into serious computing does not explain the utter lack of female hackers. “Cultural things are strong, but not that strong,” Gosper would later conclude, attributing the phenomenon to genetic, or “hardware,” differences."

I understand that people don't always remember everything they've written ever, and 40 years is a long time, but that the author of the above sentences is now suddenly surprised that there is no egalitarian culture in Silicon Valley... It says a lot about who matters.

Who owns the digital public space?

Last week, I spoke about digital public spaces and feminism in The Hague, and this is (more or less) what I said. What do you think the image below represents? Don't peek below just yet, okay?

The image shows...

A schoolyard and the paths through it taken by boys (center) and girls (right).

This image painfully illustrates how much outdoor space is created by men for boys. A basketball court is for boys, and girls just have to entertain themselves on the sidelines. A schoolyard could be made more balanced, with things in the middle that are less explicitly divided along gender lines, such as a sandbox or a climbing frame, or even, for balance, with things in the middle that are more for girls. But we have what we have, and the world changes only slowly.

Unfortunately, the physical space is not so different from the digital one; there, too, women and girls have to position themselves a little on the sidelines, otherwise something might happen to them. For example, research conducted by De Groene Amsterdammer in 2021 showed that no less than one in 10 tweets directed at female politicians are hate messages, and last week I wrote in my newsletter about research showing that online hate discourages women from entering politics. And we have known for years that the online world is toxic for women. I referred—once again—to the 2014 analysis of GamerGate by the Deadspin, which I also wrote about in De Volkskrant in the spring (in Dutch):

"What we have in Gamergate is a glimpse of how these skirmishes will unfold in the future—all the rhetorical weaponry and siegecraft of an internet comment section brought to bear on our culture, not just at the fringes but at the center. What we're seeing now is a rehearsal, where the mechanisms of a toxic and inhumane politics are being tested and improved."

But this unequal world is not what I was promised as a child, when we were all told that equality was only a few steps away.

When I applied for my current job as professor of computer science education, I was asked whether I was technical enough to be a professor of computer science. Whether I was technical enough!! Me, someone holds a PhD in software engineering from Delft University of Technology, who created a programming language, and not just as a small scientific project, but as a large global open source platform. Whether I was technical enough!! It is infuriating that someone would ask that, and that I had to remain calm and formulate a serious answer, because, well, if you throw your coffee at a future colleague, they won't hire you.

And the irony is that when I tell this story to women, their reaction is almost always: oh gosh, that's so sexist! Whereas men sometimes respond defensively, saying that the question stems from the fact that I also do other research, for example with children, as if having other skills like interviewing somehow interferes with my technical abilities. Long story short, I got the job, but after a while I moved away from the CS faculty elsewhere in the unversity, because I just wasn't feeling it for computer science anymore [[11]]

From a considerable distance from computer science (ok, not physically considerable, as I am now only about 100 meters from my old office as the crow flies), I began to concern myself with other questions. Doing more technical work suddenly felt so meaningless, because what could I to do to fit in? Create another programming language??

Over time, I became more interested in why computer science is the way it is. Why is it important to be technical? This question first led to a lengthy paper on the masculine culture of my subfield, Programming Languages.

Want to know more about that research? You can read the entire paper here, but you can also start with a 10-minute video or a 40-minute video.

Prefer a podcast? The lovely folk at Future of Programming did a whole episode on the paper!

The most important thing I described in that work is an idea I got after reading a life-changing paper for me, Glaciers, gender, and science, in which the authors describe the masculine culture of the study of glaciers (called glaciology). I knew about this paper from Twitter, where it went semi-viral [[12]] in 2016 because people found it bizarre: what does feminism have to do with glaciers?! (Even in 2025, people are still going bananas about this paper, by the way...)

But it is a paper that for me made sense, because it exposes in a very concrete way that knowledge is a social construct. This paper is definitely worth reading! What got me most was a section about the love of difficult things, in glaciology the climbing of impassable mountains. That's what gives you status, so people do it, and thus we have much more information about difficult glaciers than about those near people, which is counterintuitive and perhaps also not so useful, because understanding the glaciers in residential areas may be of more practical use. They might soon come down and destroy entire villages.

I read and reread the paper and concluded after a while: this is aptly describing computer science. We may not climb mountains, but our social status does come from complexity: complicated algorithms, complex programming languages, processing lots and lots of data, these are our high icy mountains. Interviewing people, acting ethically, thinking about inclusivity, these are the low village glaciers where you don't want to be found dead.

And not only is complexity something we consider important, it is the only thing we consider important. While some doctors or lawyers may also love a super-complex bypass operation or plea, there are also those who choose that profession to help people or to make the world a better place based on a more abstract idea. We don't have that in computer science. Research shows that the biggest reason for not choosing to study computer science is the importance of social change:

"First is the persistent negative association between social activist values and the pursuit of computing careers; women and men who place greater importance on helping others and effecting social change are less likely to pursue computer science in college" Source: Sax et al, 2016

And the complexity is also used as a shield against all responsibility. Governments that want to rein in big tech? They don't understand a thing. "Normal people and governments", as Eric Schmidt, former CEO of Google, said last year, “aren't ready”. Philosophers, psychologists, linguists, or anyone else who doesn't come from a computer science background don't understand algorithms on social media or AI or LLMs and (therefore) should just keep quiet about this inevitable progress.

And so here we are, in a world where chatbots promise children a "beautiful suicide."

If there had been another product doing this, like an energy drink or a new Advil, it would have been taken off the shelves immediately, or never made it there in the first place, because food and medicine are strictly regulated (and for good reason, of course). But somehow, intervening in the world of software is considered too complicated to attempt, or bad for the economy. If you try, the tech bros will call you a Luddite (a term that, fortunately, has made a comeback, according to this lovely article in n+1 magazine).

If you were wondering why I am eager to write thousands of words criticizing AI week after week, it is because this response doesn't apply to me. You can't accuse me of not understanding how algorithms work, so people listen to me differently. Very often, when I speak at schools about AI and say that AI is not inevitable or intelligent, teachers feel so relieved! They already thought so, but they don't dare to say so because they don't trust themselves to understand AI well enough.

So I concluded my argument on Wednesday by saying: even if you're not a software person, you know enough! I know enough about cars to know that I don't want one, I don't need to know how the motor itself. If you don't want software from a company that sells “teenagers who feel worthless, insecure, stressed, defeated, afraid, stupid, or worthless” as a product, or continues to push the extreme right (both links in Dutch) you don't need to know exactly how it's programmed!

If you're convinced and want to get rid of (American) big tech, Paris Marx has a nice howto!

Is vibe coding the death of programming?

If so, then we have done it ourselves.

When people ask me how my research is going, I don't really have a ready answer these days. Whereas I used to be fully engaged with Hedy, and always had something cool to report—a new feature, a new language, a study running somewhere—my research is now much less tangible in terms of concrete progress.

Where I used to think that the problems in our field could be solved with programming—if languages aren't inclusive, then I'll build them to be more inclusive, case closed—I now focus more on the question of why problems arose in the first place. This is partly due to the response to my work to make programming more inclusive, for example by allowing people to program Arabic or Chinese. I thought it was just a teeny tiny mistake that we hadn't built non-English languages into Python, C, or Java. Just didn't think about it. So I had thought (very naively, I know) that if people saw Hedy in non-English language, they would think: ah cool, we can do that too! I wrote a paper on with former colleague Alaaeddin Swidan on how to build multilingualism into your code.

However, many programmers were not enthusiastic at all, au contraire! They thought it was too much effort, because "they" could "just" learn English, right? Or they found it disturbing that the woke left had now also reached the design of programming languages.

So I slowly but surely shifted my focus, not to: how do we solve this problem, but: why did this problem arise? How is it possible that I took five courses on creating programming languages in CS, but no one told me that 1+1 is not the same in all languages and cultures? Why did we learn everything about the history of C, C++, Java, ABC, and PASCAL, but nothing about programming languages and systems from other cultures, such as experiments in the Soviet Union to create a ternary, non-binary computer? You would expect that be exciting, just like a programming language with only whitespace.

And how is it possible that John von Neumann, a man personally involved in choosing Hiroshima and Nagasaki, not only features extensively in our curricula (fair enough, he is known for the Von Neumann architecture), but also is the namegiver of an IEEE award? What does that say about our values?

One of the things I think about a lot is how we define programming, which is very hard to do. In a paper I wrote a long time ago (from 2017, long before Hedy!), I described how the process of programming is somewhat similar to the process of writing a book. Writing as a term is similarly vague, and yet we can deal with it just fine. Everyone understands that when I say "I'm writing a book", I don't just mean typing on the keyboard, but also planning, deleting, rereading, and communicating with a publisher, and maybe even given a talk about my book is part of it.

In programming, views are completely different. For most people, programming means only typing code on a computer [[13]]. When people hear that you are a programmer, they think of codes like in the move the Matrix, not someone walking around with a notepad asking people how they do their work and how software could help them.

That idea doesn't come out of nowhere; it's starts in education. When I was a student, there were courses called Programming 0 (haha, counting starts at 0, of course!) through 5, and they were all about wel... programming, which we practiced with tiny problems such as printing prime numbers, reversing pieces of text, or searching in a list. (Actually, it starts even earlier, when we tell secondary school students that mathematics is incredibly important for computer science, and because computer science is very often part of mathematics and science faculties and departments).

Subjects other than programming and mathematics are placed far later in study programs, and are also approached in a mathematical way. A course on testing, for example, is more often about testing theories, techniques and frameworks than about user testing with people. After all, that's not your job later on, that's what a tester does! Or a subject called something like Requirements Engineering, which sounds very difficult and technical, but is just “asking people what they want.” And you only need to learn that indirectly, because talking to customers is something a product manager does for you. You get to type code all day long!

This removes the humanity from the profession of programming, and creates the image that programming is very, very difficult, which makes you feel smart as a programmer (see also: climbing glaciers). In recent years, salaries in tech have certainly stengthened that image. If you can earn that much, you must be able to do something very special.

But unfortunately, here comes the AI train! Typing code happens to be something that LLMs are pretty good at (or at least seem to be good at!). Anyone can code, and suddenly programmers are no longer needed. That's the hype du jour after all, even though it seems not really working that way, and suddenly programming is no longer such a special skill. Oops.

Had we focused more on the human side, on really listening to what people need, our profession might not have been so eroded. Because what's really difficult about making a good product is understanding what's happening in the real world and then translating that into code.

Question by a reader: what opinions should you give a platform?

Following on from last week when I wrote about Michiel Bakker, a reader wondered whether such an interview is actually a good idea. The journalist probably hopes that his assertive statements (e.g. about people being machines) speak for themselves, in the hope/expectation that the public will see through them, but is that really the case?

It's a classic dilemma. Do you give space to Nigel Farage or Trump to voice their opinion? Or someone like Joe Rogan or Charlie Kirk? They are influential voices, but an interview also makes them more visible.

The first thing that came to my mind was a piece from 2012 by John Oliver, in which he begs Donald Trump to run for president. Hahaha, that would be hilarious. Well, not so funny now, I think, now that people are literally being snatched off the streets by masked ICE agents.

For the most part, I think the old saying is true: there's no such thing as bad publicity. Having your name in the news, in whatever form, is good for your brand. If it's in the good old legacy media such it has a legitimizing effect. And the opinions out in the wild force people (almost always marginalized people) to explain over and over again why these opinions are harmful and dangerous and wrong. This takes time, energy, and frankly also happiness to have to explain over and over again why problematic things are problematic, as I wrote back in 2016.

Moreover, elections are often won not on opinions, but on issues, so if you determine what the topic of conversation is, you have already won the battle. This is also known as “agenda-setting theory.” (Dutch right winger Wilders understands this very well, as evidenced by a good analysis by NRC in Dutch of his recent tweets, in which he writes almost exclusively about migration).

Media, as Bernard Cohen said back in 1963, "may not be successful much of the time in telling people what to think, but it is stunningly successful in telling its readers what to think about." If the newspapers constantly talk about tighter borders, even right wing politicians are calling for things that are currently impossible under constitutional law, it is still the topic that dominates the debate.

Other parties see that extreme positions are receiving attention time and time again, and they are also shifting, as Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer recently mentioned in HP/de Tijd (in Dutch, but this phenomenon of course occurs elsewhere too).

"Under Wilders' influence, the Overton window has shifted so far to the right that a former centrist party like the VVD is sufficiently threatened by Wilders at the polls to adopt his extremist positions. In a sense, Wilders' role is now over. He is no longer needed. He has already won. His fascism has become mainstream."

This means that the extreme parties do not have to adjust their positions at all; in fact, they can move further to the fringes. What appears to be compromise thus becomes a one-sided battle, so well described in AR Moxon's book Very Fine People: [[14]].

"Meet me in the middle, says the unjust man.

You take a step towards him, he takes a step back.

Meet me in the middle, says the unjust man."

Now, I am not saying this is happening just because of journalism! We can't blame journalists alone for that! Social media also plays a role, as do various crises such as COVID-19, and Ukraine, which have repeatedly sparked new discussions about boundaries and government interference, which in turn has led to the platforming of certain opinions, which has provoked reactions, etc., etc.

Okay, so much for the classic dilemma; none of this has anything to do with AI yet. With AI, it's slightly different. Because while people might, in theory, still think, "This is completely outrageous!" when hearing statements by Farage, Kirk or Trump, this is almost impossible when it comes to AI.

Due to the the shield of complexity (see also above), computer scientists have succeeded in excluding "normal people" from the discourse because they don't understand what it says. A university lecturer at MIT, well, he must know, right? And his friends and acquaintances must all be super smart too, right? Well, if they all agree, then that's not a very weak appeal to authority but a rock-solid argument.

And in the AI discussion, we simply don't know. Bakker says (translated):

"We are ultimately biological computers. And why couldn't a non-biological computer do the same? I don't see any fundamental limitations."

Well, in a sense, you have to agree with him. In some magical way that we don't understand at all, humans can do things. We have unraveled some things, but there is still so much we don't know. How does a thought form? As I type this, somewhere in my body, in my head, but new research shows also in other parts of your body such as the intestines, something is happening that ultimately leads to my fingers typing letters on a keyboard. Could you replicate that entire process on a computer? Perhaps. Personally, I don't think so, because I believe there is such a thing as a soul, something that makes you unique as a human being, a mix of your personality, upbringing, and your body, but others are free to believe that a computer can indeed do that. What Bakker says is not so much complete nonsense as it is a belief.

Bakker is a physicist. How does he actually know that a human being is a biological computer? What does the word computer mean in that sentence? Do people do nothing more than calculate? Don't they also feel emotions, stress, panic? Can you calculate things that are not rational? I am now old enough to admit that much of my research and my thinking is driven by my feelings.

I think it's unfair that women are not allowed to contribute to the digital world, which makes me angry, and that's why I'm motivated to devote so much of my computational power to it. Those feelings stem from 25 years of being a woman in the IT world and gaining experiences that are unique to me. There are very few people who have spent years as (almost) the only woman in a lecture hall, and there are very few people who have created a programming language and have seen first hand how angry it make some people if it is suggested programming languages could be made more inclusive.

My experiences, combined with my character and my upbringing, make me do things, know things, want things. Even if you believe that a computer can think, do you really believe that computers will ever come in all shapes and sizes? The worldview that remains unnamed is the worldview of the natural sciences, in which knowledge is separate from the knower, and in which such a calculating computer is not unique, but smarter/better/wiser than all humans combined.

This is also clearly evident in statements such as “Where and how that power is used should be determined by all of us.” As if there is one correct answer that we just need to vote on, instead of a multitude of voices, genders, cultures, languages, all wanting something different. It seems highly unlikely to me that many newspaper readers think this kind of thing when they read that sentence.

And so we can continue this way of thinking from a philosophy of science perspective, because what does biological mean? Do we also include the intestinal flora, are we going to simulate that in the PC as well? Possible maybe, but it's not something that science is currently focusing on. And what about human reproduction? Roughly half of humanity can create new humans with their bodies, and that is not exactly a conscious cognitive process. It's not as if pregnant people keep track of which genes they are going to choose in an Excel spreadsheet, or that they create an index finger or a right lung with pure willpower.

If you think about it for a moment, you will quickly come to the conclusion that the fact that a computer will not be able to make babies in the foreseeable future is quite a fundamental limitation. Here too, on closer inspection, a view of humanity becomes clear, namely a view in which only human thought counts as human, as something that must be simulated. All the other things that humans do—pooping, singing, having sex, getting angry, mourning, etc., etc., etc.—immediately expose the fundamental problems that Bakker sweeps under the rug. Again, it seems highly unlikely to me that many Volkskrant readers think these kinds of things when they read that sentence, because what is and is not thinking, what is human, has been the subject of a great deal of philosophy for 2000 years (and probably much longer). It is not a puzzle that a programmer can solve in a instant; it is an ongoing debate with a wealth of beautiful, ugly, crazy, and strong opinions.

That is why the opinion "if people read this, they will see that it is nonsense" does not really work for AI. They see that someone, who is put on a pedestal by the system we have created in which the natural sciences are at the top of the food chain of intelligence, and then their image of humanity becomes a kind of fact.

And what happens in many articles about A(G)I is actually Cohen in action. The conversations on AI concern about whether or not it can think, whether it is intelligent or super-intelligent or hyper-intelligent or whatever new term they have come up with, and whether that will pose existential risks in the future, not about the multitude of problems that AI is already causing!

Events

- On October 30, I will be on stage with John Hattie and Gert Biesta! Very cool!

- On November 11, I will speak about the history of AI in Amsterdam at the Eurostar conference.

Good news

Okay, I was probably the last person to discover this, but I still had a good laugh when I heard that the boss of Nintendo America is called Doug Bowser! Has there ever been a more apt name than a boss who has the name of a boss?

Hooray, there is something that can be done about all that CO2 in the air! A company in Eindhoven has created a device that can absorb 3 tons of CO2 per year. Carbyon promises that the next version will be 25 times more effective, removing 75 tons per year, which is roughly the emissions of five Dutch households. Great, that will really make a difference!

The Dutch government (except for the Tax Bureau, see below) is becoming increasingly aware of the problems of Big Tech, not only the dependence but also the high license costs (for products that can often be replaced by free open source packages), so they are now going to investigate this.

The Consumentenbond (Association of Consumers) is also getting involved in the AI discussion, which is very good and very justified! Twenty of the 70 Google AI answers they examined were, according to them, "outdated, too assertive, too simplistic, or too commercial." That's striking, they say, because the feature often pops up unasked. It's nice that they mention the tip to use "-AI," to make the hallucinations will stay away!

More and more Americans see betting on sports as bad for society, with this view increasing among young men in particular from 22% in 2022 to half in 2025.

Okay, it's not news because the original piece is from 2020, but I'm including it anyway because it's so beautiful. In Finland, they know how to solve homelessness, namely by giving homeless people, you guessed it, a home. It's good news, but also very sad, of course, that a simple intervention is not being considered in so many places, including the Netherlands, because others would complain that it is unfair, or expensive, or difficult.

"In this increasingly polarized society" is something you hear everywhere, but is that really the case? Science communication hero Michel van Baal dived into the data from the Netherlands and saw that trust in other people and in the justice system has actually increased over the past 12 years!

And as a delightful final note, Dutch non profit Bits of Freedom has won their lawsuit against Meta. Dutch users of Instagram and Facebook must be able to choose a chronological timeline by default (rather than one that is algorithmically generated with each new visit, as it is now). Meta has two weeks to fix this, also with become of our upcoming elections.

Bad news

In a timing that couldn't have been more bizarre, this week we saw that our Dutch tax bureau will be moving to the Microsoft cloud after all (Dutch) Such projects run for ages, of course, but it is still remarkable that it is being pushed through at a time when digital sovereignty is more important than ever.

Did I write in Good News about how the as-yet-unbuilt new version of the CO2 "vacuum cleaner" can remove the emissions of as many as five Dutch families? Unfortunately, that costs about as much energy as four households... A good example of how hypothetical technology can lull us back to sleep with "we'll solve that later."

CarpetRight has gone bankrupt, partly due to a failed software project. Yet another example of "20 years of digitization, zero effect."

And it's not just the indiscriminate introduction of software that is bad for business operations, but also acquisitions by private equity. Research in the US compares hospitals that have been taken over with similar ones and finds that those owned by private equity have 13% more deaths, mainly due to the dismissal of people who, in hindsight, turned out to be very necessary.

Enjoy your sandwich!

[[1]]: Nu wat dit incident niet het enige dat dat veroorzaakte, ik was de informatica om een hele hoop andere gebeurtenissen ook beu, maar dit incident was zo verweven met mijn positie zelf dat het me pijn bleef doen.

[[2]]: Let op, link naar Twitter/X. Niet mijn favoriete plek maar het geeft wel inzicht om te zien hor het paper toen besproken werd.

[[3]]: Soms, maar niet vaak, wordt voor deze nauwe betekenis ook wel 'coden' or 'coderen' gebruikt, en in oudere papers bijvoorbeeld bij Cognitive Dimensions of Notation gebruiken ook nog 'transcriptie' (transcription)

[[4]]: Help me eraan herinneren dat ik daar nog steeds wat over moet schrijven, voor zijn nieuwe boek gaat uitkomen!

[[11]]: While this incident was not the only thing that caused this, I was tired of a whole host of other events as well, but this incident was so intertwined with my position itself that it continued to hurt me.

[[12]]: Note, link to Twitter/X. Not my favorite place, but it does provide insight into how the paper was discussed at the time.

[[13]]: Sometimes, but not often, the terms ‘coding’ or ‘encoding’ are also used for this narrow meaning, and in older papers, for example in Cognitive Dimensions of Notation, ‘transcription’ is also used.

[[14]]: Remind me to write something about this book, before his new one comes out!

Member discussion